Émilie Bérard

The notions of transformation and multiplicity were constant vehicles for artistic and technical emulation in Van Cleef & Arpels’ creative output.

Transformable jewelry is “designed so that it can be transformed and made into other pieces thanks to detachable ornaments.”1Marguerite de Cerval, ed., Le Dictionnaire international du bijou (Paris: Éditions du Regard, 1998), 527. These elements can “be worn separately, partially, combined, or recomposed [to form new compositions]. This reversibility is an essential element.”2Anna Tabakhova, Clasps, 4,000 Years of Fasteners in Jewellery, trans. Valérie Charonnat (Mézidon: Éditions Terracol, 2016): 150. [Note that all quotations from this book cited here are freely translated from the French edition.] Transformability and the multiplicity of functions and ways of wearing Van Cleef & Arpels’ creations were in keeping with the tradition of transformable jewelry.

Fashion, mother of transformability

The history of transformable jewelry is linked to that of clothing and to socioeconomic contexts. “In the Middle Ages, belt settings were detachable, with chains serving both as necklaces and as belts.”3Marguerite de Cerval, ed., Le Dictionnaire international du bijou (Paris: Éditions du Regard, 1998), 527. Under the Ancien Régime, those with power—monarchs and aristocrats— wore gemstones on their clothes, sewn onto fabrics, or removed in keeping with the fashions and tastes of the time. In the nineteenth century, notably during the Second Empire41852–1870. when the bourgeoisie adopted the codes of the nobility, haute couture began to emerge in Paris.

Rue Napoléon, created in 1806 at the Emperor’s behest and renamed Rue de la Paix in 1814, benefited from the reorganization of the new Opéra district, becoming the heart of luxury French commerce. There, couturiers and jewelers rubbed shoulders in a symbiotic relationship. The English fashion designer Charles Frederick Worth moved to number 7 Rue de la Paix, while the jewelers Mellerio (aka “Meller”) and Vever were at numbers 135Meller was based at number 9 Rue de la Paix following the street’s renumbering in 1851. and 19 respectively. Meanwhile, the goldsmith Louis Aucoc presided at number 6 and the fan-maker Duvelleroy occupied number 15. The fashion houses Paquin and Boué Soeurs then moved to Rue de la Paix later in the century. Women’s clothing and jewelry developed in parallel, producing various functional variations to meet the ever-growing number of social events.

Transformable dresses, for example, came into being with at least two different bodices: one with sleeves for the daytime, the other without for evening wear. Jewelry also lent itself to transformation. The diadem, the showpiece of an upper-class bride’s wedding attire, was the emblem of transformable jewelry. In order to offset the cost, it was made up of brooches that were attached to a metallic structure with butterfly screws, also called butterfly nuts. The brooches could be worn by themselves, or together as a stomacher, and were reserved for balls or weddings when mounted as a diadem.

Transformable jewelry from the late 1930s

Until the late 1930s, Van Cleef & Arpels’ transformable jewelry was characterized by relatively simple, removable fastening systems inherited from the past, notably from nineteenth-century jewelry. In 1924, the Maison designed a long necklace featuring a floral arrangement in a vase. This Art Deco-style piece was composed of a platinum chain and pendant that could be worn as a brooch, enhanced with enamel, onyx, sapphires, emeralds, buff-top rubies, and rose-and brilliant-cut diamonds. The chain was made of oblong openwork elements in onyx, interspersed with diamonds, and rectangular motifs set with diamonds, some of which were decorated with floral elements. The pendant could be detached from the chain thanks to a butterfly screw and threaded hole system.6A threaded hole is the complementary form of a threaded screw or rod. It is a smooth hole into which something is threaded. Based on the age-old nut-and-bolt principle, this system provided a relatively easy and quick method of fastening.

A long necklace that turns into a bracelet

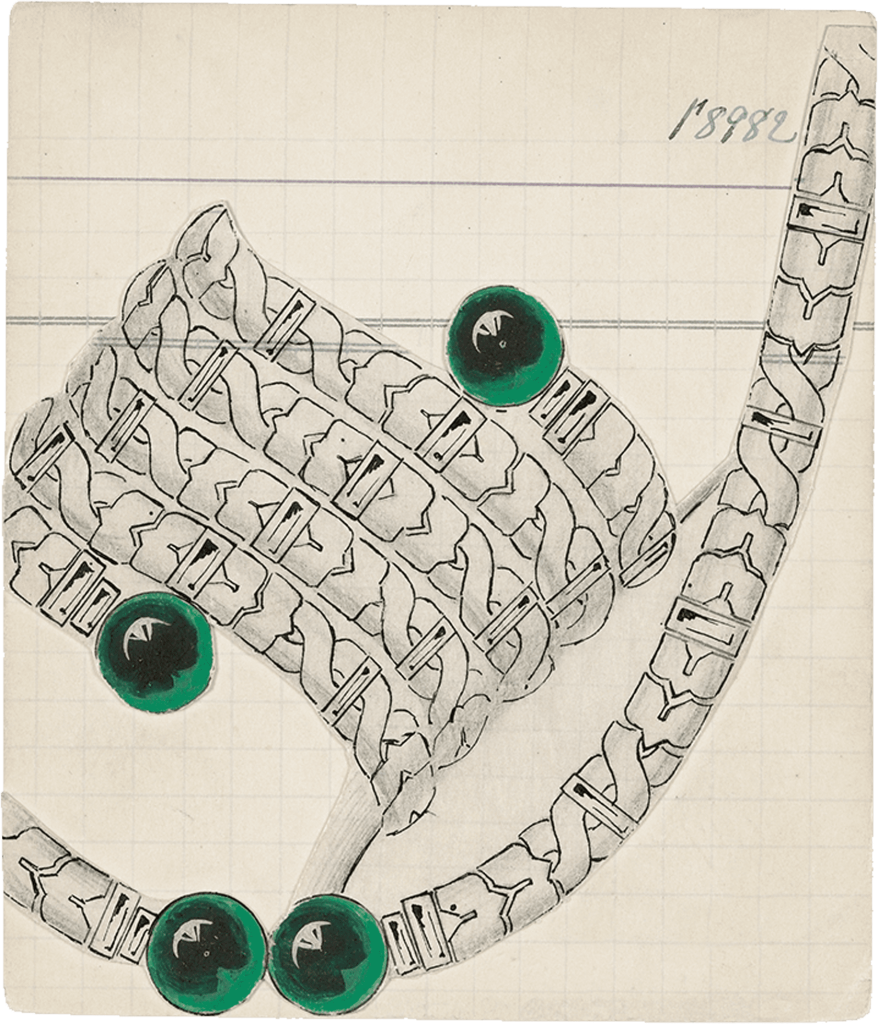

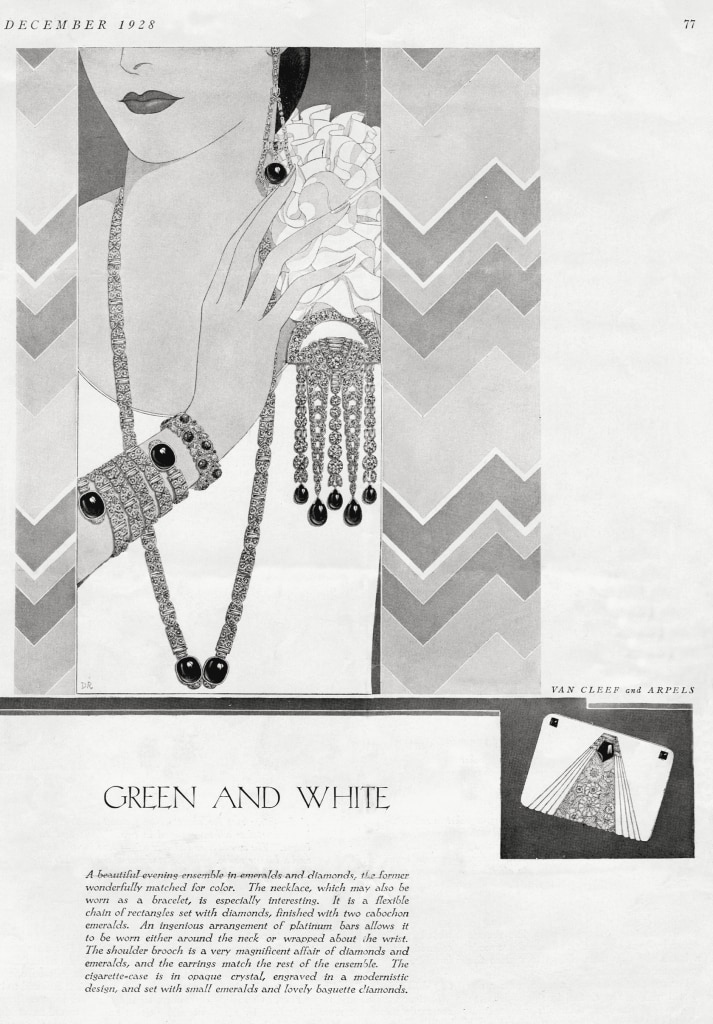

The word “transformable” first appeared in the Van Cleef & Arpels Archives in 1928 in reference to a “diamond sautoir with two emeralds, transformable into a bracelet”.7Product card. Paris, Van Cleef & Arpels Archives.

This piece was in keeping with the long necklace and tie-necklaces typical of the Maison’s output in the late 1920s, and featured in an advertisement in the December 1928 issue of Harper’s Bazaar. “The necklace, which can also be worn as a bracelet, is particularly interesting. It is a flexible chain of rectangles ending in two emerald cabochons. An ingenious arrangement of platinum bars enables them to be worn around the neck or wrist.” The systems used here harked back to a form of fastener called a “mobile pin fastener” or “rod and knuckle,” developed by the Egyptians during the New Kingdom (1552–1069 BCE).8Anna Tabakhova, Clasps, 4,000 Years of Fasteners in Jewelry, trans. Valérie Charonnat (Mézidon: Éditions Terracol, 2016): 19: “During the New Kingdom period, circa 1552–1069 BCE, articulated cuffs and flexible bracelets with rows of threaded beads were found, closed with a rod inserted into a ‘knuckle’, a popular form of fastener in the Orient at that time, otherwise known as a ‘a mobile pin fastener’ or ‘key fastener’.”

Van Cleef & Arpels was therefore using an ancient fastening system, skillfully inserting it onto a link chain to transform the piece from a necklace into a bracelet. Once again, the system was simple and relatively easy to use.

Detachable double clips

The distinguishing feature of a transformable piece of jewelry is its plurality: fastening systems enable several pieces of jewelry to be concealed within a single piece, affording different style of wear depending on the occasion. During the 1930s, detachable clips that could be separated into two distinct parts were immensely popular, their clip systems with springs or pins allowing for different ways of wearing them. Some of these double clips were joined together by a pawl fastener,9Anna Tabakhova, Clasps, 4,000 Years of Fasteners in Jewelry, trans. Valérie Charonnat (Mézidon: Éditions Terracol, 2016): 254: “A fastener composed of a blade serving as a spring, the pawl, and a rectangular, cylindrical or oval box. […] The point where the finger is placed to press or free the pawl is called a thumb piece or push button.” a legacy of sixteenth-century jewelry.10Anna Tabakhova, Clasps, 4,000 Years of Fasteners in Jewelry, trans. Valérie Charonnat (Mézidon: Éditions Terracol, 2016): 61: “The first pawl boxes were found in the late sixteenth century in Northern Europe.” The motifs found in these transformable pieces were frequently inspired by the world of fashion design.

The double clip in platinum and diamonds dating from around 1935, as well as the 1937 double clip in platinum, rubies, and diamonds, could be worn in their full versions on a lapel or in a hairstyle, or separated into two distinct, asymmetrical parts to adorn a dress or hairstyle. The arrangement of the different-sized gemstones was reminiscent of the lace used for fans, while the play of two colors highlighted the originality of each of the two parts.

Detachable double clips were also seen on bracelets, once again enabling multiple styles of wear, whether as bracelets, double clips on lapels, or hairpieces. A rare version of a “bracelet in gold Ludo fabric forming two clips, rubies and diamonds, with a platinum mount”11Product card. Paris, Van Cleef & Arpels Archives. was created in 1937. The double clips displayed billowing pink gold ribbons and platinum set with diamonds. They were fixed to the upper part of the Ludo mesh bracelet, composed of a hollow structure in the shape of a double bridge set with rubies, with the help of double claw hooks on the back of the two pieces. As such no additional system was required. This bracelet was one of the earliest Van Cleef & Arpels’ pieces to have a registered design.

Floral and plant motifs in transformation jewelry

Floral-and plant-inspired designs, inherited from eighteenth-and nineteenth-century French jewelry, were also subject to transformation. Motifs thus revealed hidden forms, not noticed at first glance. The Peony double clip created in 1937 in platinum, yellow gold, diamonds, and mystery set rubies, displayed two flowers; one in bloom, the other bending under the weight of its petals. Like transformable stomachers of the past, this double clip could be worn with the two peonies together or separately.

Peony clip

The brooch dating from 1936, in platinum, diamonds, and sapphires, could also be worn in two different ways, as a whole or with the wild rose on its own. The flower was detached thanks to a relatively simple system, also inherited from the nineteenth century—a wedge inserted in a hole that held the two parts of the piece in place, while a butterfly screw joined the whole thing together.

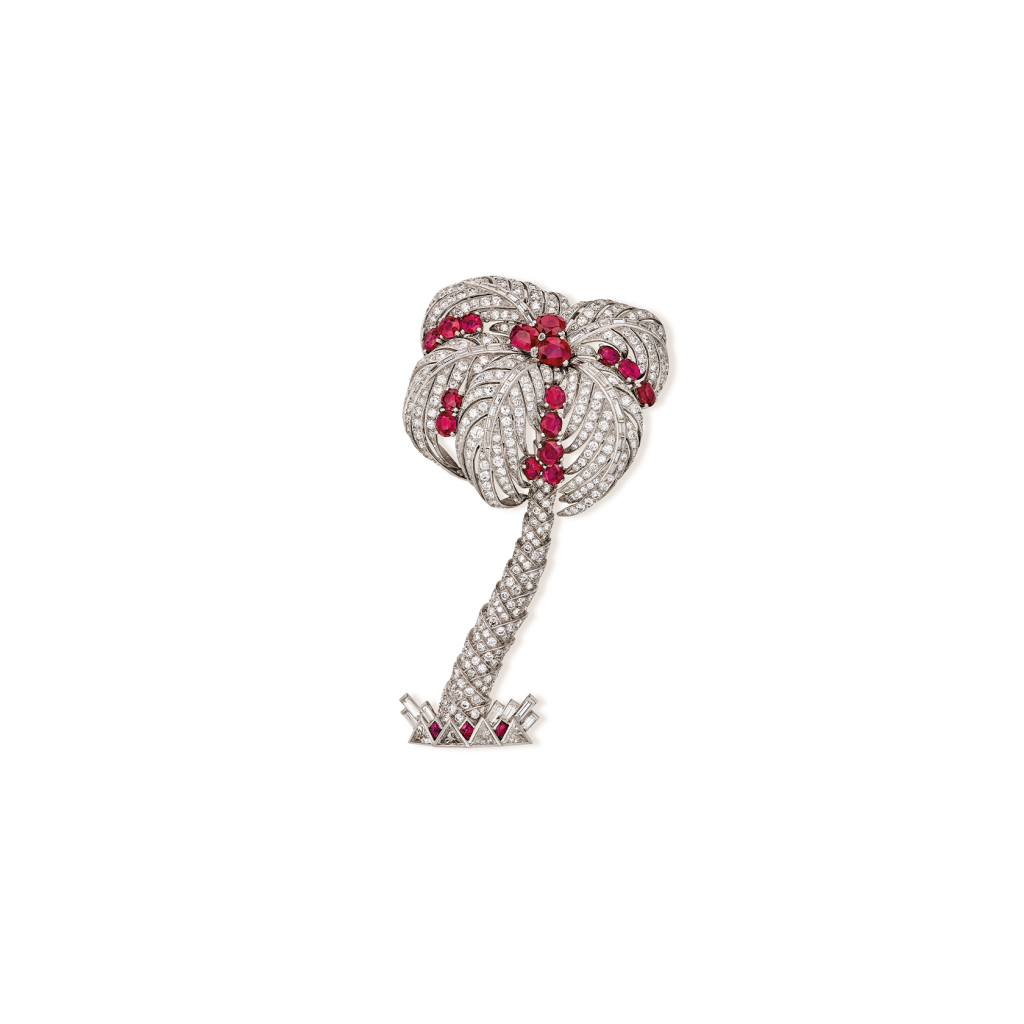

The Palm Tree clip in platinum, rubies, and diamonds, dating from 1941, had an upper section that could be detached thanks to a clasp and push-button system. Once again, a wedge was inserted in a hole to stabilize the trunk and palm fronds and facilitate the joining of the two parts. The palm fronds were unfastened from the trunk and could be worn separately.

The 1951 Tulip clip was also composed of two clips of platinum and diamonds that, when assembled, constituted the corolla of a tulip flower. A separate element that espoused the form of the clip systems served as the backbone onto which these two pieces could be united with a transversal brooch. When separated, these two clips formed two distinct pieces of jewelry: a “bean” or flame shape that was a popular motif of the Maison, and a tulip, smaller in size than in the full version. In this way, one piece of jewelry revealed another. This example was directly inspired by nineteenth-century transformation systems whereby different pieces could be attached to a separate element that echoed their shape to form a whole.

Another type of assembly was seen in the plant-inspired earrings commissioned by Her Royal Highness Princess Fawzia of Egypt in 1951 which were composed of two parts linked by a so-called “swan’s neck” hook system and ring12Anna Tabakhova, Clasps, 4,000 Years of Fasteners in Jewelry, trans. Valérie Charonnat (Mézidon: Éditions Terracol, 2016): 246: “Hook and ring fastener, with a hook on one side and a loop, ring, or eyelet on the other. Hook and rings could be doubled or bent into S-like staples.” that enabled them to be worn as a short version known as ear studs, or a longer pendant version. The so-called “swan’s neck” system, inherited from the Bronze Age13Anna Tabakhova, Clasps, 4,000 Years of Fasteners in Jewelry, trans. Valérie Charonnat (Mézidon: Éditions Terracol, 2016): 246: “Hook and ring fastener, with a hook on one side and a loop, ring, or eyelet on the other. Hook and rings could be doubled or bent into S-like staples.” (circa 2400–1500 BCE), was used throughout the twentieth century for detachable earrings and pendants, thanks to its simplicity.

The Passe-Partout and Zip, icons of the technical evolution of transformable jewelry

In the late 1930s, Van Cleef & Arpels’ transformable jewelry underwent a revival, adopting technical developments that broke with the transformation systems of the past. These developments reflected a societal change whereby the aim of transformable jewelry was no longer solely to save money by virtue of acquiring several pieces for the price of one, but was also a playful choice that tended towards a statement of individuality and personal style. Inspired by the industrial era and Modernism, Van Cleef & Arpels, together with the Péry workshops, went on to create two transformable pieces of jewelry whose stylistic and technical features were to become icons: the Passe-Partout and the Zip.

The Passe-Partout jewelry

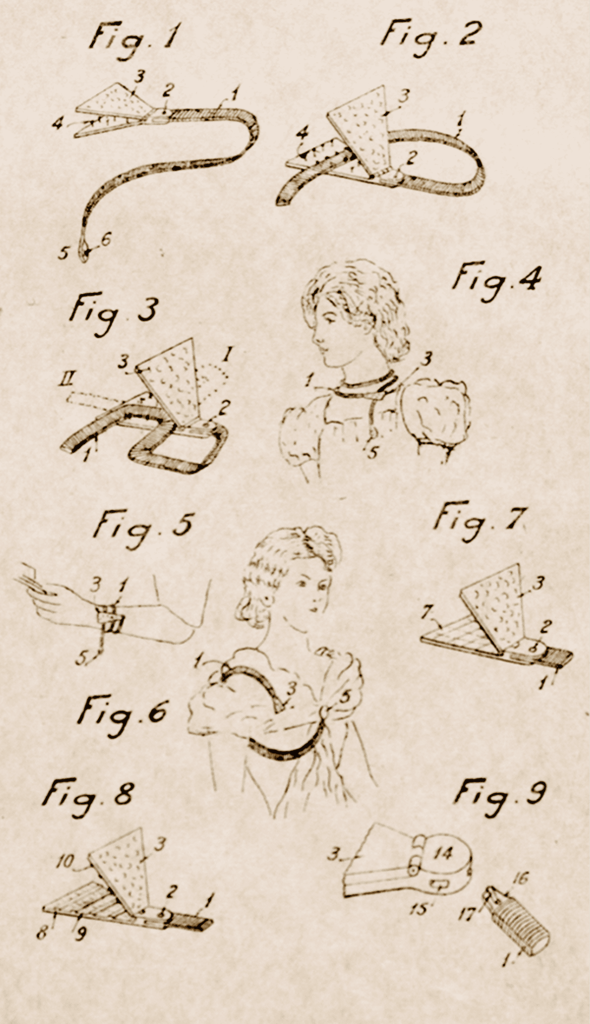

The Passe-Partout (“all-purpose” or “versatile”), patented in 1938,14Patent invention no. 834.209 requested on February 24, 1938, by Van Cleef & Arpels S.A.R.L. and registered on August 8, 1938. The Passe-Partout became a registered trademark on March 8, 1939, no. 300.123. could be worn on any occasion, hence its name.15Letter in English from Claude Arpels to a client, dated December 19, 1946. Paris, Van Cleef & Arpels Archives. It was a multiple piece combining tradition and technical ingenuity.

It heralded the historical revivalism developed by Van Cleef & Arpels in the 1940s and 1950s, as well as embodying the “modern” style of the late 1930s. The Passe-Partout symbolized the Maison’s creations for the French Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair inaugurated in 1939 with the slogan “Dawn of a New Day.” The theme of this exhibition was the future, expressing the event’s desire to distance itself from the Great Depression.16The Great Depression, eferring to the economic crisis of the 1930s, followed on from the 1929 Wall Street Crash in the United States, and lasted until the Second World War.

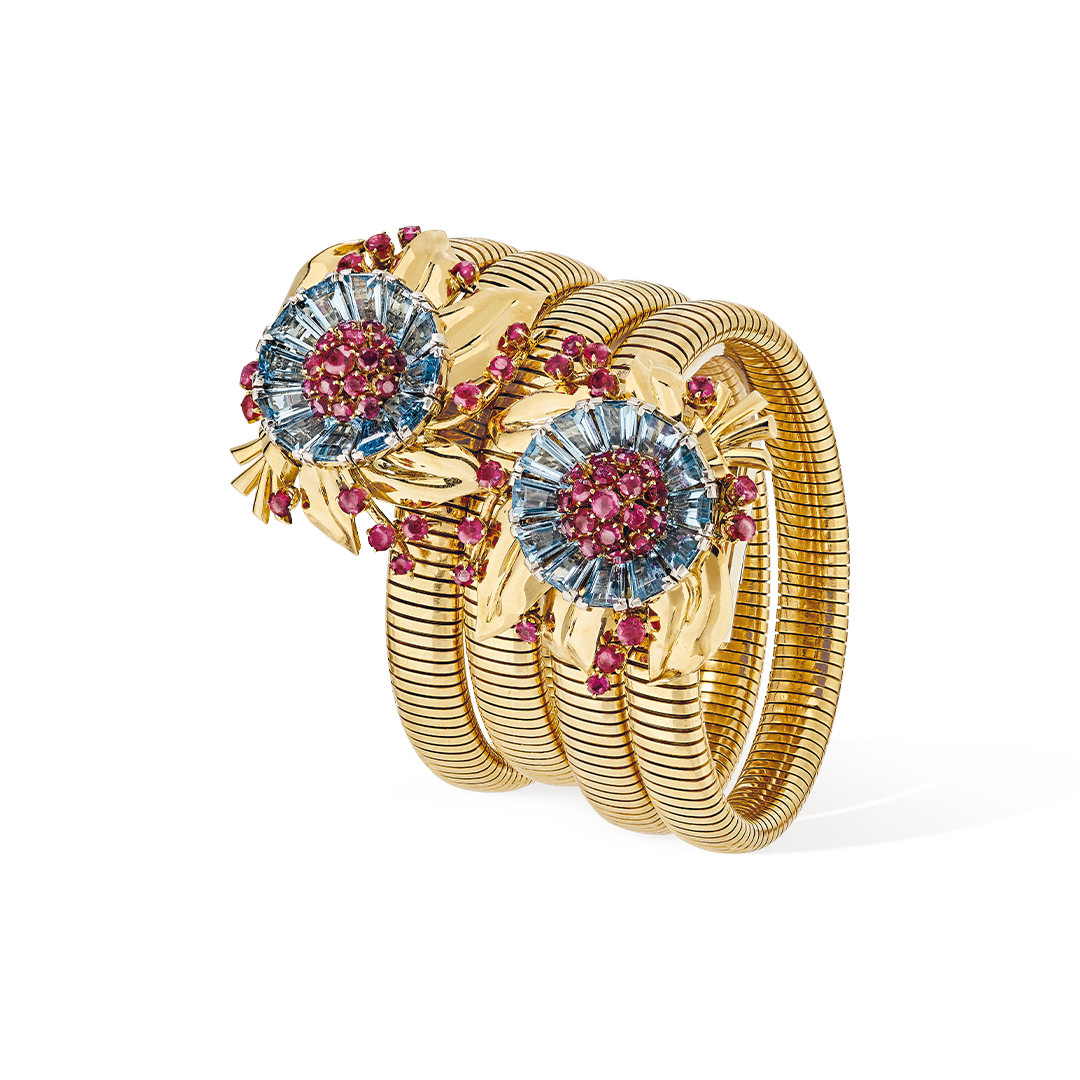

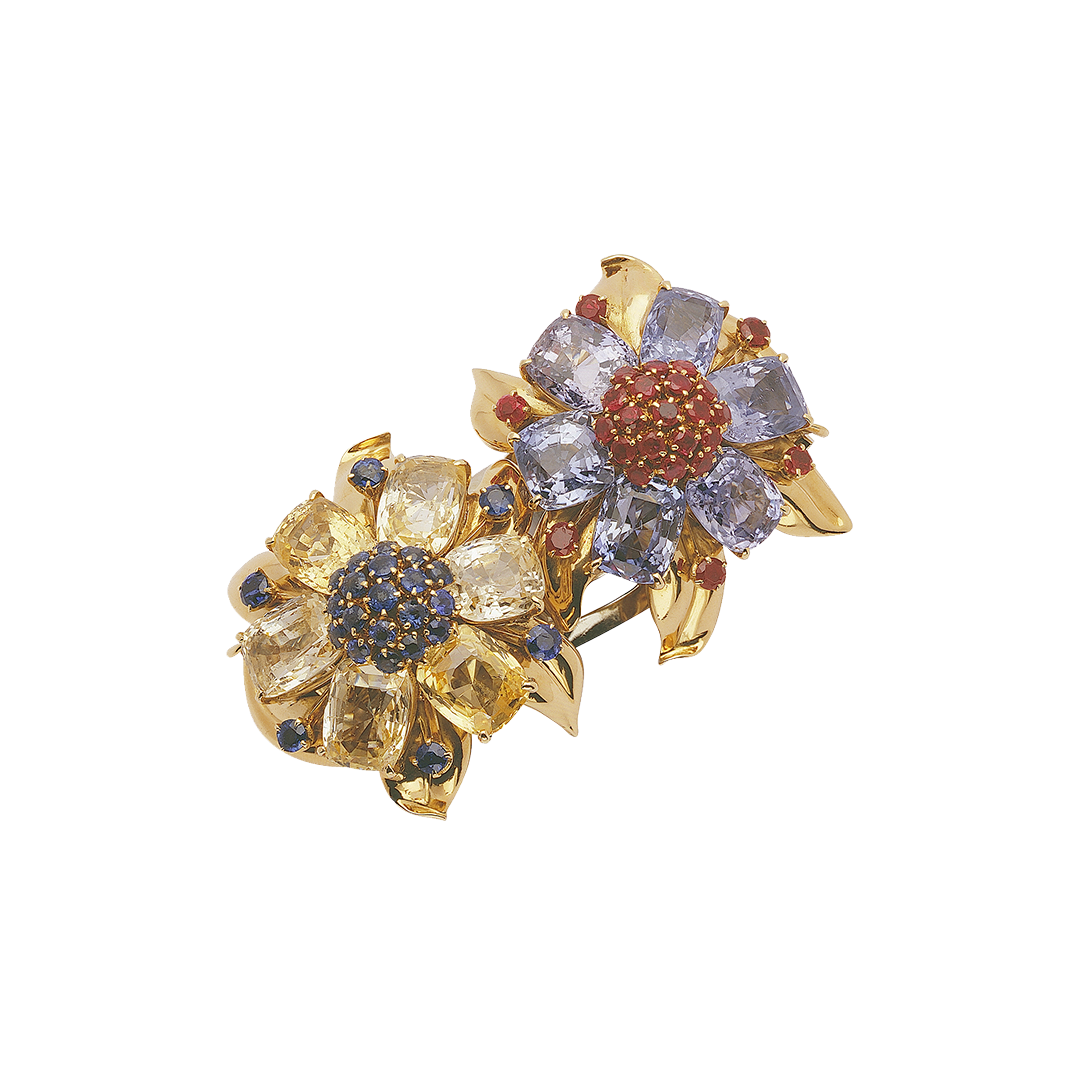

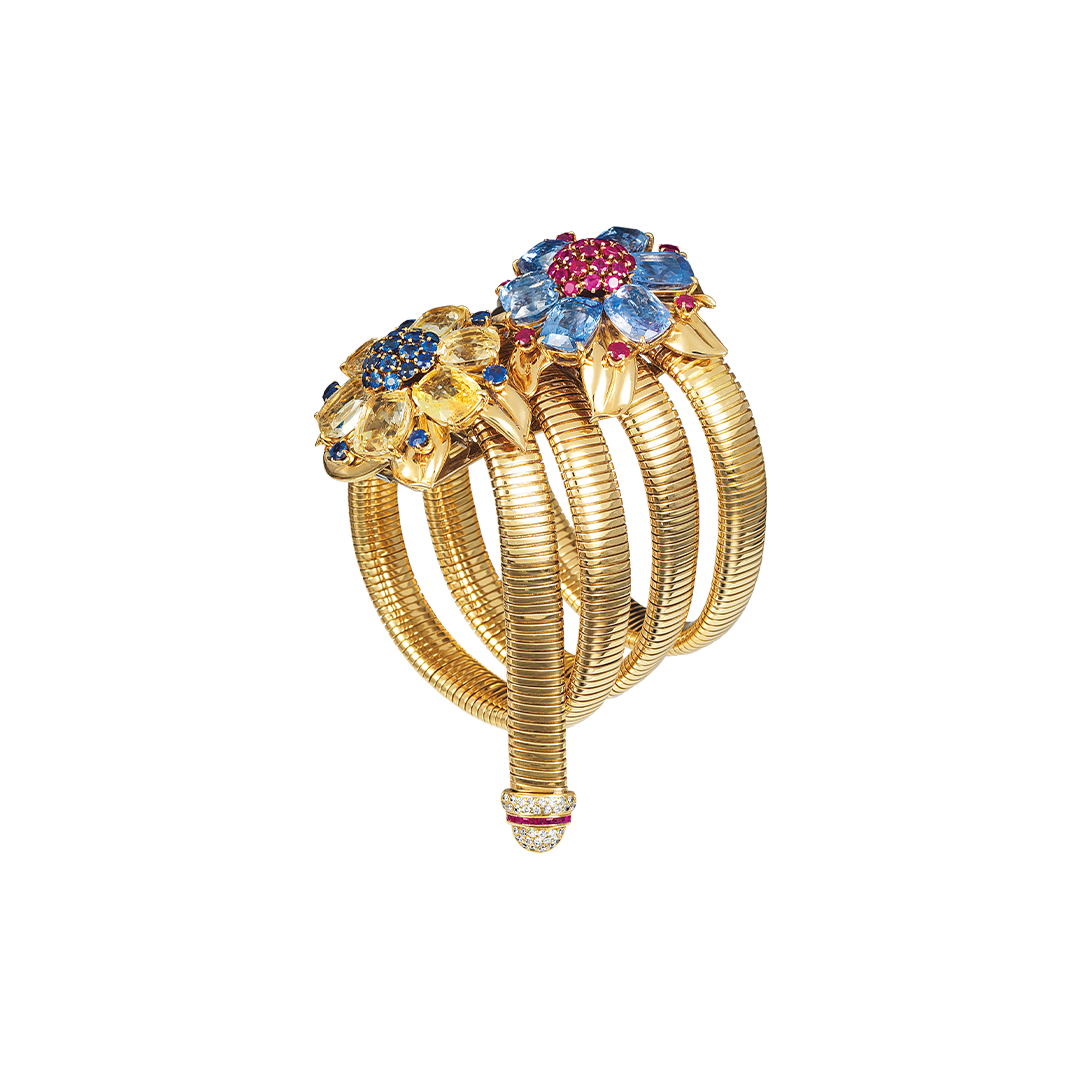

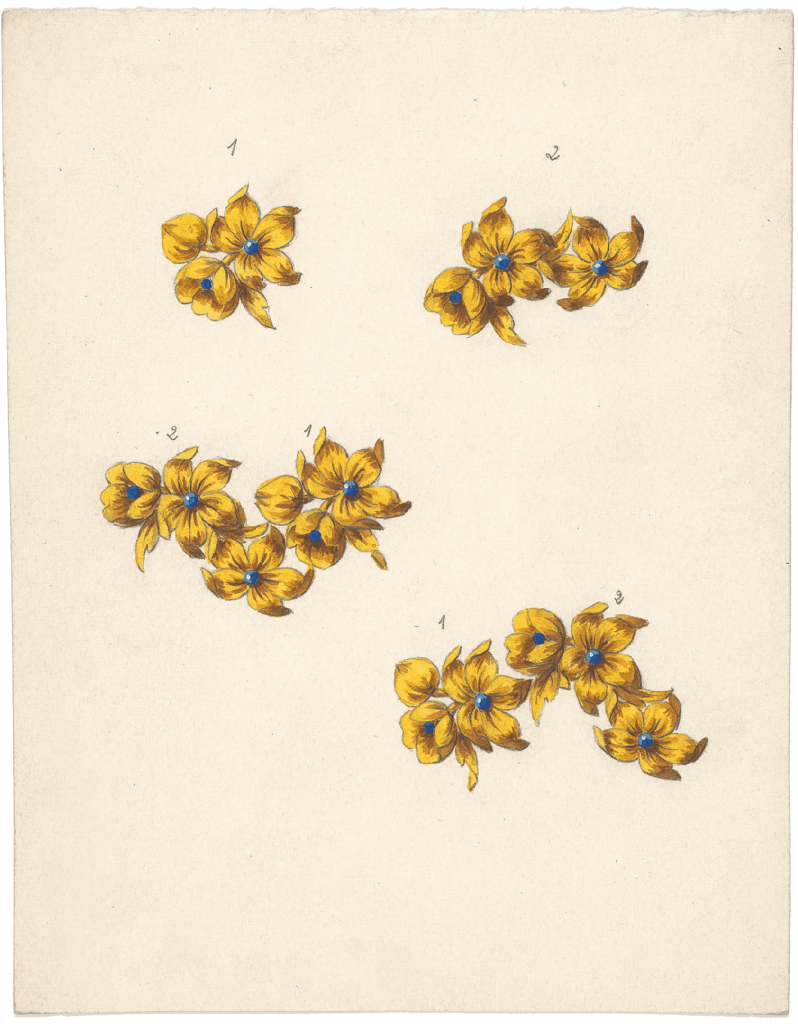

The Passe-Partout illustrated an unusual confrontation between a structure known as a Tubogas chain—in reference to industrial tubes, inherited from the work of nineteenth-century chain-makers17Henri Vever, French Jewelry of the Nineteenth Century (London: Thames & Hudson Ltd, 2001) (Freely translated here from the French edition, first published in Paris by H. Floury, Libraire-Éditeur, 1906, pp. 346–348): “These chains […], a great novelty, were made with a gold thread approximately one millimeter wide, almost flat or gutter-shaped, that was tightly wound in a continuous fashion, like a coiled spring, each spiral fitting into the previous one without any soldering. Once finished, this type of work produced flexible yet solid necklaces that resembled flattened snakes or long, annulated reptiles. All widths of highly flexible and practical chains, necklaces and bracelets were made in this way. Auguste Lion (1830–1895), who made a detailed study of this kind of work, took it to great heights of perfection, the vogue for which, started under Napoleon III, lasted for over twenty years.”— and the stylized look of the flower clips. Tubogas consisted of coiling a host of gold threads around a steel bore, creating a mesh typified by its elasticity and flexibility. The Passe-Partout’s relatively wide, flat chain highlighted the industrial aspect of the piece. Each of the flowers’ petals was depicted by a single gem. The pared-down form of the flowers and buds, together with the combination of primary colors, with their play of sapphire blues and yellows along with ruby reds, gave this reinterpretation of eighteenth-century stomachers a decidedly modern appearance.

The ingenuity of the Passe-Partout lay in its gold clasp composed of four rails, hidden by the Flower clips, that served to adjust the Tubogas chain and multiply the piece’s functions, from short or long necklace to stomacher, bracelet, or belt. “The invention is for a piece of jewelry essentially composed of a ribbon and a clasp that can move in various directions in relation to the ribbon. The clasp has devices to which the ribbon can be attached and held in place at different positions at various points along its length (possibly at any point along its length). In a variant [never actually made], the ribbon, unlike the clasp, bears a stapling device that can assume the shape of a decorative motif.”18Patent invention no. 834.209 requested on February 24, 1938 by Van Cleef & Arpels S.A.R.L. and registered on August 8, 1938.

The Flower clips could be detached from the clasp and worn separately as ornaments on the front of dresses, in the hair, or as earrings. The direction in which the clips were fastened was indicated on the back of the clasp with arrows. The technical ingenuity and multiplicity of transformations afforded by the Passe-Partout made it one of Van Cleef & Arpels’ emblematic creations.

The Zip jewelry

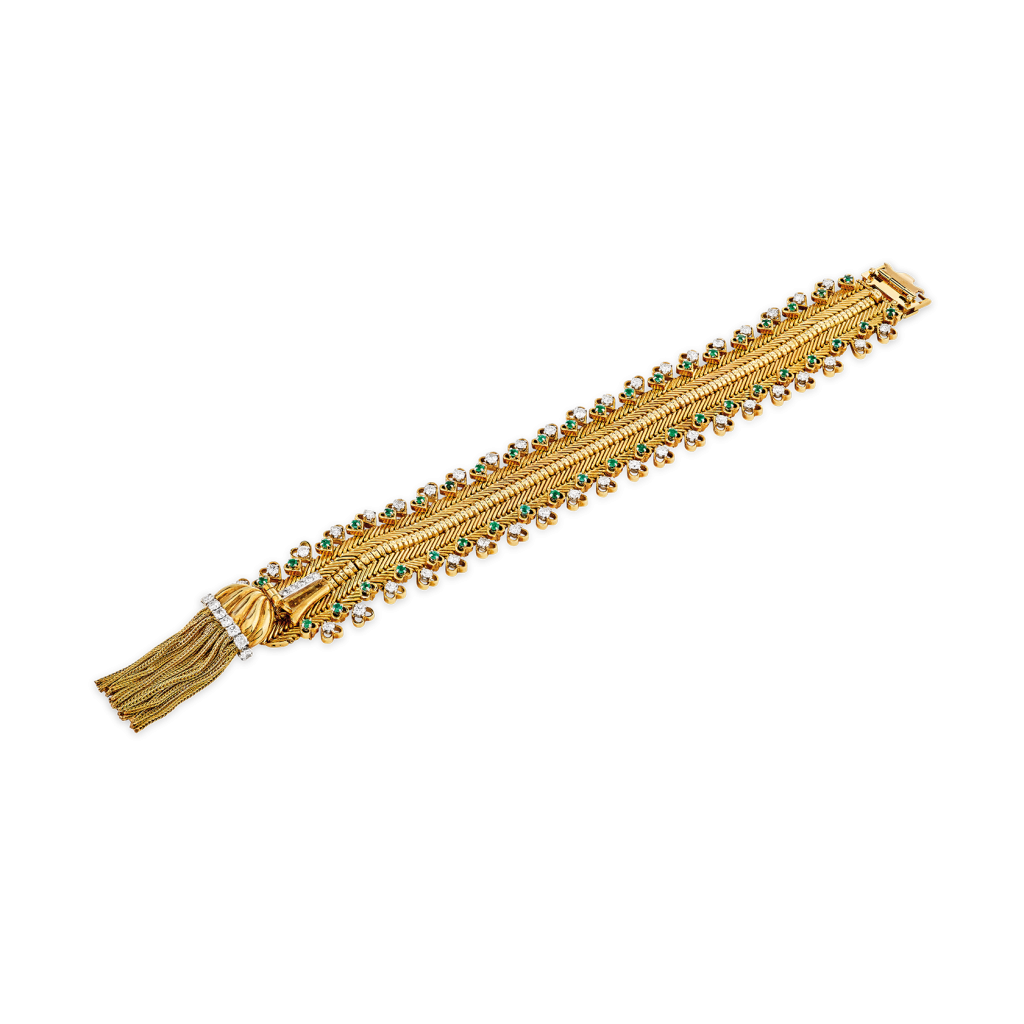

“Wearing an accessory open as a necklace when it is normally intended to be closed” demonstrated the creative and technical symbiosis that existed between Van Cleef & Arpels and Ateliers Péry, “[…] [daring] to take the opposite view at a time when extravagance was praised.”19Anna Tabakhova, Clasps, 4,000 Years of Fasteners in Jewelry, trans. Valérie Charonnat (Mézidon: Éditions Terracol, 2016): 166. The Zip, as its name indicates, was a piece “that opens as a necklace and closes as a bracelet”20Anna Tabakhova, Clasps, 4,000 Years of Fasteners in Jewelry, trans. Valérie Charonnat (Mézidon: Éditions Terracol, 2016): 166. with the help of a tassel. It was made of gold or occasionally platinum, and was the result of great technical prowess, perfected over the course of nearly thirteen years, the Second World War having interrupted its creation.

The Zip was made up of four parts that varied according to how it was assembled. Worn as a necklace, it consisted of three parts : the first, an extension of the upper part of the piece, was placed at the back of the neck; followed by the central part, worn unzipped; and lastly, a finishing section was attached to the tassel. These three parts were linked by pawl box fasteners.

For the bracelet version, only the central part of the piece was used, zipped up, displaying “two [fastener] boxes joined edge to edge,”21Anna Tabakhova, Clasps, 4,000 Years of Fasteners in Jewelry, trans. Valérie Charonnat (Mézidon: Éditions Terracol, 2016): 166. with “two pawls positioned top to tail on the back of the piece: one, a double pawl, that fits into the double box on one side, the other, a wider pawl that closes the bracelet on the other side.”22Anna Tabakhova, Clasps, 4,000 Years of Fasteners in Jewelry, trans. Valérie Charonnat (Mézidon: Éditions Terracol, 2016): 166.

Due to its originality, the Zip was hugely successful during the 1950s, and became an icon of French jewelry. It paved the way for a prolific range of transformable jewelry that was to mark the Van Cleef & Arpels style in the following decades. In the 1960s, for example, pendant necklaces that could be adjusted into short or long necklaces, as well as transformable bracelets and clips, led the way as the Maison’s signature pieces that went on to ensure its commercial success.