Solène Taquet

Its founding at Place Vendôme in 1906, the creativity and originality of Van Cleef & Arpels’ artefacts and accessories have never ceased to surprise its clients. Whether purely decorative or more functional, these creations have accompanied the everyday lives of these clients both men and women, in their homes and elsewhere.

In the Maison’s archives and Patrimonial Collection, these creations are divided into two main categories: objets d’art, with or without some form of timepiece, and jewelry accessories. The Maison’s objets d’art are typified by their stature: they can be placed on top of furniture and admired, but do not fit in a pocket. They have specific functions, ranging from commonplace to unusual, such as the telescope sold in 1912.1Van Cleef & Arpels debit book dating from October 25, 1912. Paris, Van Cleef & Arpels Archives.

The Varuna, the first item of the Patrimonal Collection

The reduced-scale model of the yacht Varuna is the oldest item in the Patrimonial Collection, commissioned in 1906 by Eugene Higgins,2See “Eugene Higgins, Host to Society,” New York Times (July 30, 1948): 17. a well-known figure in New York society. The enameled gold boat is depicted traversing a sea of sculpted jasper, on top of an ebony base. The rough sea carved by the lapidary illustrates the Maison’s desire to depict nature as alive and permanently moving, as seen in many of its creations. This piece was originally electrified, the boat’s main funnel serving as an electric bell to summon the owner’s butler.

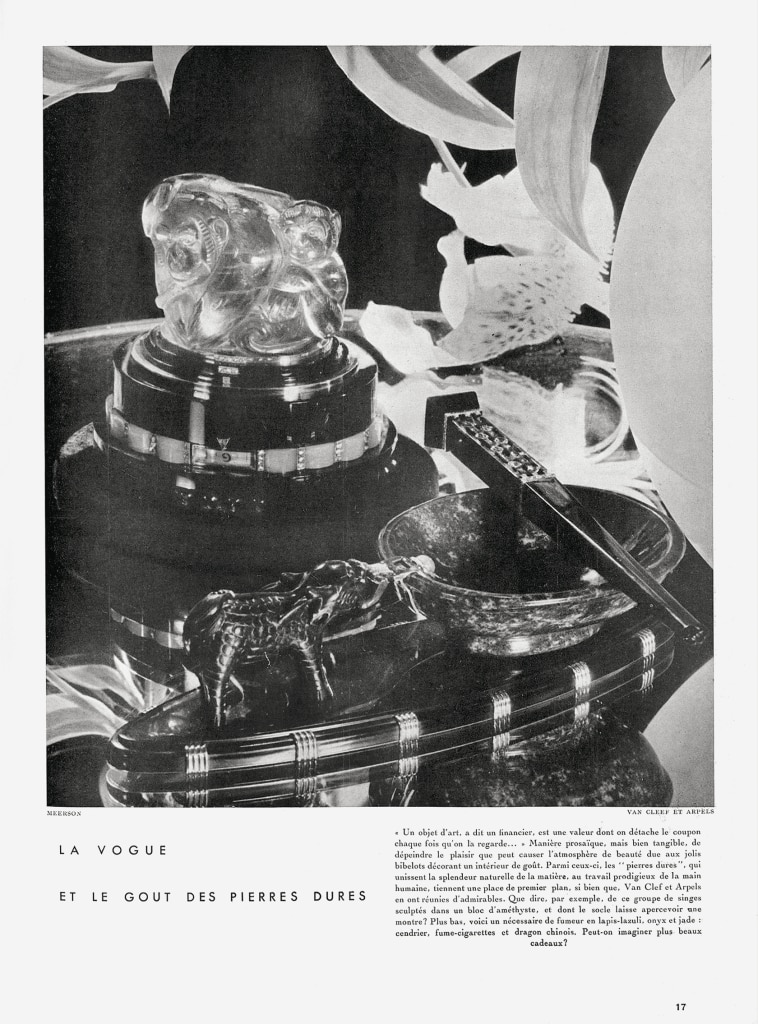

The taste for hard stones

While cutting techniques were of primary importance in the creation of these artefacts, the selection of gemstones was also what distinguished them. This was the case for the blocks of pink quartz cleverly used for a bedside lamp dating from 1930. In addition to the lamp’s base, four pink quartz geometric forms punctuate its cylindrical yellow-green lacquer lid, as well as its top with a stepped circular motif. When the lamp is turned off, the pink quartz is purely decorative; when it is turned on, however, its translucency allows the light of the electric bulb, hidden beneath the lid, to shine through the material and its inclusions, diffusing its aura. This bedside lamp also stands out for its use of the contrasting colors of yel- low-green and pink, and their opaque and translucent qualities that reflect light to a greater or lesser extent, as well as for the ingenious use of the mineral’s properties.

This taste for ornamental stones was the subject of an article published in a French fashion magazine from November 1934, which stated that “The objet d’art [is associated with] the pleasure that a beautiful atmosphere emanates, thanks to pretty trinkets tastefully adorning an interior […]. Can you imagine finer gifts than those made by Van Cleef & Arpels combining a material’s natural splendor with the skill of the human hand?”3Meerson, “La vogue et le goût des pierres dures,” Femina (November, 1934) : 17.

Van Cleef & Arpels also received highly original commissions like the Maison d’Hortense, a precious yellow gold cage with a sculpted lapis lazuli water basin and branches of coral, originally intended for a tree frog, possibly belonging to a maharaja. The animal was known to perch at different heights on the ladder depending on the temperature, thus providing an indication of the weather forecast.4The zoologist Auguste Duméril (1812–1870) suggested the idea of a living barometer read with the help of a batrachian in his Catalogue méthodique de la collection des batraciens du Muséum d’histoire naturelle de Paris, in 1963. Bibliothèque Nationale de France: https://data.bnf.fr/fr/ temp work/67b1ea 82e6579b a5c828cc13 3008c412/.

Tableware

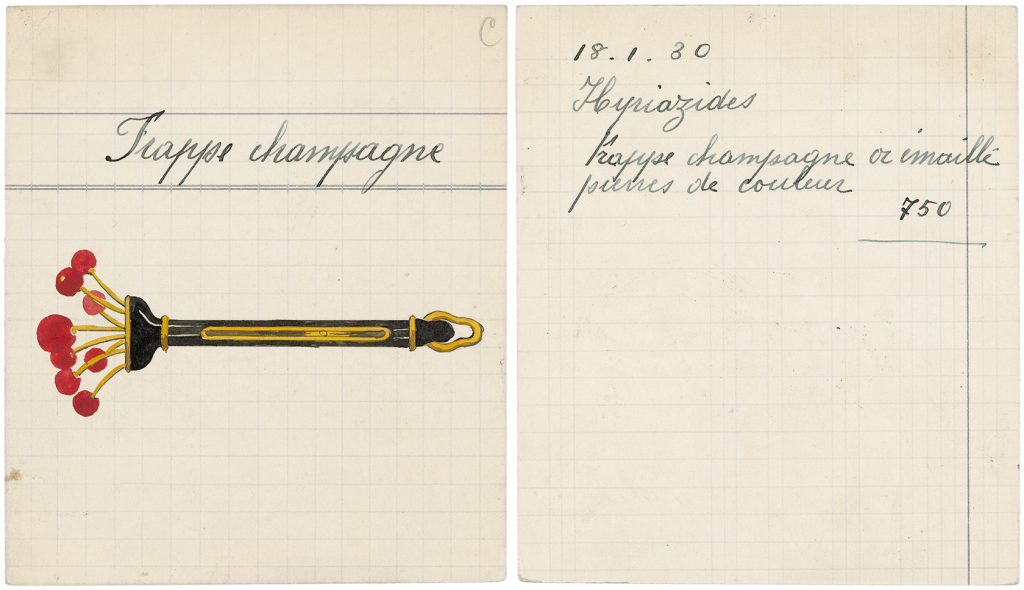

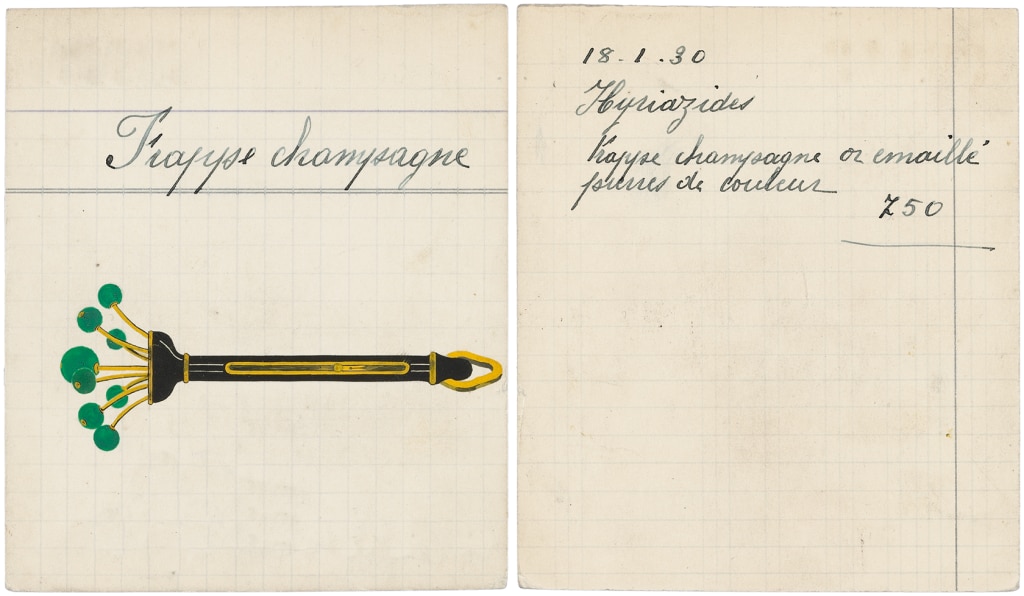

Tableware is another area where we find unusual commissions. Some of these pieces, mainly associated with goldsmith-work, are represented in the Maison’s archives and Patrimonial Collection. An egg serving set dating from 19095Van Cleef & Arpels debit book dated September 18, 1909. Paris, Van Cleef & Arpels Archives. is one such example, together with another one from 1945, as well as a gold porridge pan, probably a gift for a birth. The champagne whisk, midway between an accessory and table art, is another type of artefact made by Van Cleef & Arpels. Also known as a champagne stirrer or swizzle stick, the champagne whisk is retractable and serves to remove the bubbles for those who do not like the sensation of them on their tongue. Some examples dating from the 1930s are noted in the Archives as being decorated with colored stones, while later versions were entirely made of gold, like the one conserved in the Patrimonial Collection.

Objects that tell the time

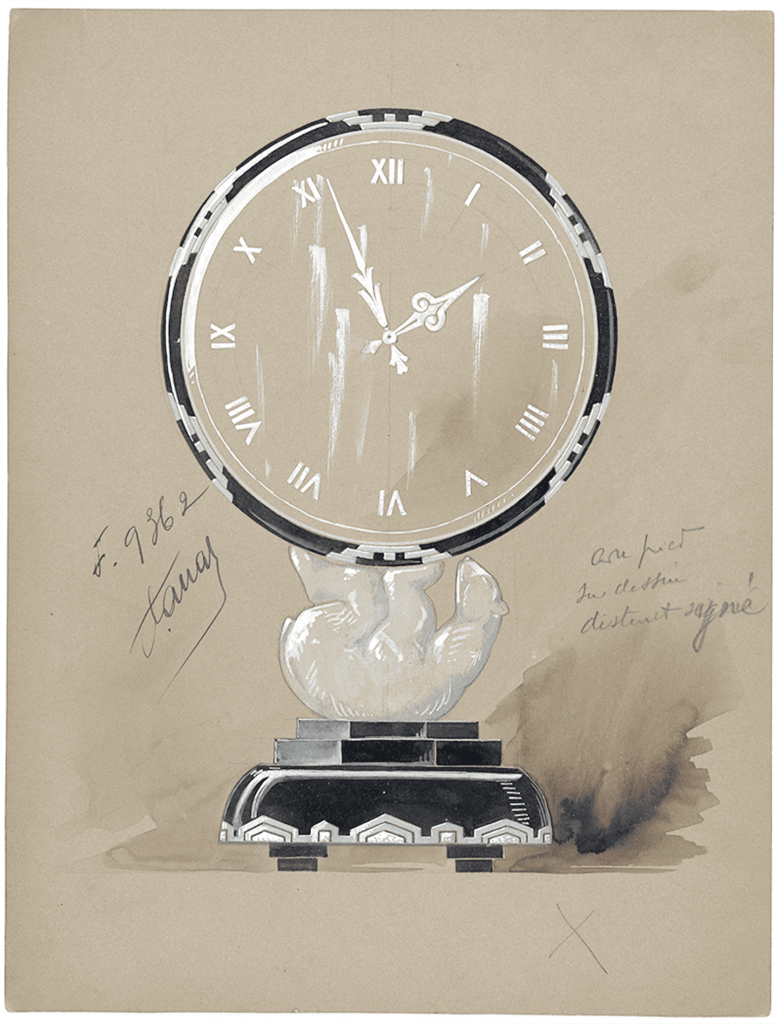

Among the many objets d’art created by Van Cleef & Arpels, those with a timekeeping function stand out. They accompany the passing of time with elegance and ingenuity. Clocks had been available to clients since the 1920s, notable for their mystery pendulums,6The Mystery pendulum consisted of a dial made of transparent material onto which hands were fixed that appeared to move forward without any visible mechanism. This illusion was enabled by a system of rotating crystal disks, each linked to a hand and a cog attached to the frame, in order to link up with the mechanism hidden in the base. invented by Robert Houdin,7https://www.maisonde lamagie.fr/1087-robert- houdin-horloger.htm. an enthusiast of “scientific amusements.” This interest was revived in the 1990s with the creation of the Homage to Galileo clock8This clock was sold for 165,000 euros by Pierre Bergé & Associés on December 9, 2002., whose circular dial is upheld by the paws of a bear pavé-set with diamonds. The complexity of this mysterious clock lay in its invisible mechanism that not only enabled the central motif to rotate full circle, but also kept it upright. A white mother-of-pearl moon depicted against a starry sky in lapis lazuli added a narrative touch to this work of art.

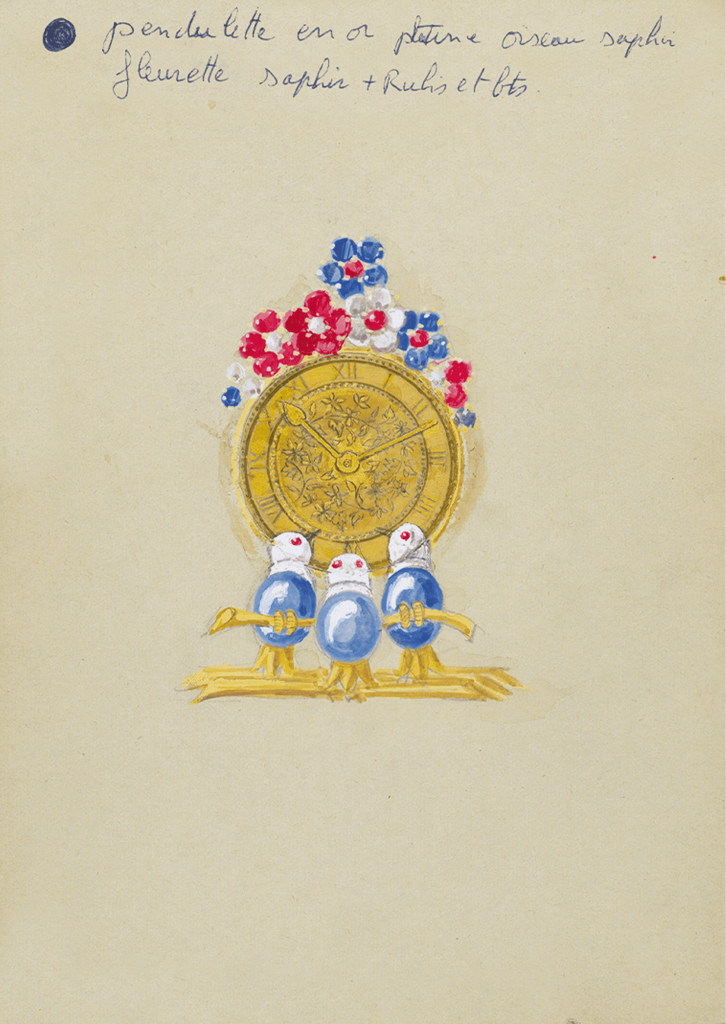

Table clocks provided an iconographic repertory that explored nature in a state of perpetual renewal, decorated with rock-crystal flowers and animals set with colored stones. Two multicolored birds made of lapis lazuli, jade, and rubies, dating from 1928, enabled the time to be read thanks to one of them resting its beak on a revolving dial. As for those perched on timekeeping creations dating from the 1940s and 1950s, they echoed the Lovebirds brooches of the same period. Shown in pairs or in families; perched on the stems of Hawaii flowers or forget-me-nots, these birds were decorated with sapphire and ruby cabochons, their spread wings gleaming with diamonds.

Table clocks also drew on a bestiary from distant lands: monkeys carved in deepest amethyst, bears pavé-set with diamonds in the 1920s, and pandas in contrasting colored stones in the 1990s.

Renewed interest in ornamental stones and organic materials

The interest in natural minerals and organic materials such as wood gave rise, in the 1970s, to paperweights inlaid with clock faces edged with threads of twisted yellow gold. During the same period, the Greek opera singer Maria Callas, a prestigious client of the Maison, purchased a marine chronometer that she offered to her friend Hélène Rochas, another equally illustrious Van Cleef & Arpels customer. A dial inserted in a hemisphere is fixed in a spacious box made of exotic sipo wood in such a way as to oscillate with the movement of the waves. This remarkable artefact now forms part of the Maison’s Patrimonial Collection.

Men’s jewelry

The accessories produced by Van Cleef & Arpels fall into several categories: those linked to clothing, money, writing, smoking, beauty, and timekeeping. At the turn of the century, it was good form for a well-dressed man to wear a pin in his tie or cravat, decorated with a flying duck, a horse’s head in profile, or a simple pearl.

Gentlemen’s waistcoats and jackets had small pockets that could fit fob watches, round for the most part, held by thin chains. These garments could be adorned with waistcoat or dickey studs, and cufflinks for the shirts. While studs are no longer worn, the latter are still seen today.

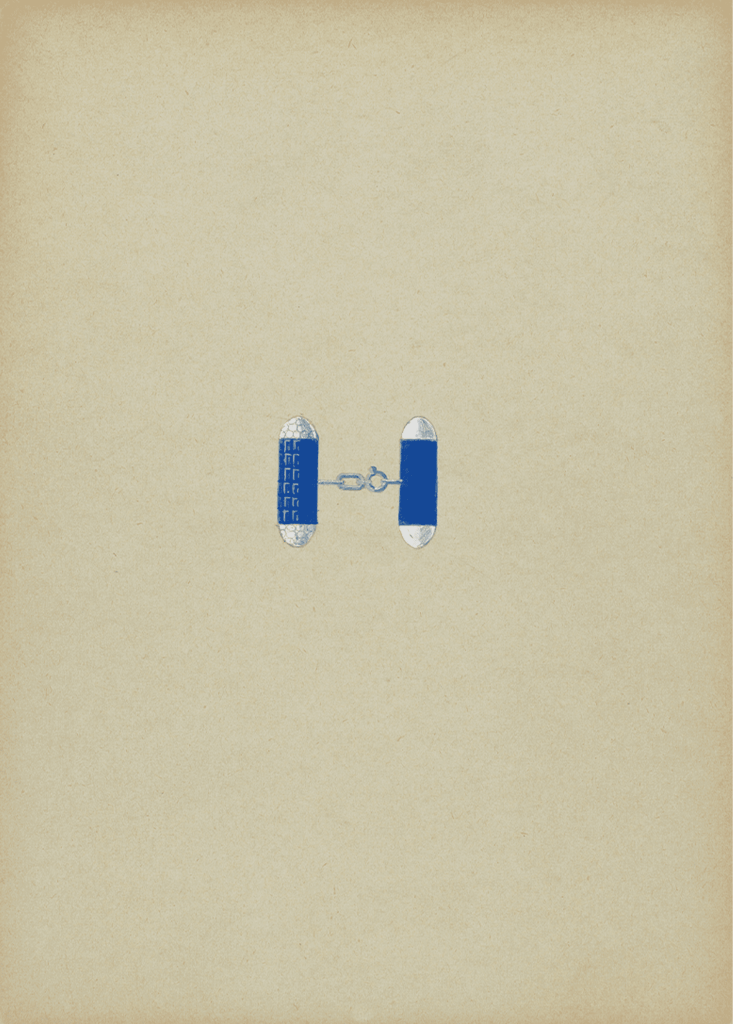

Throughout the twentieth century, the design and styles of these clothing accessories, mostly for men, reflected the art movements and fashions of the period. From the 1900s to mid-1930s, these discreet objects were decorated with a range of thin, geometric plaques: round, hexagonal, octagonal, or square. In the 1920s, these geometric compositions, reversed out of metal or made with calibrated stones, were heavily inspired by the Art Deco movement. After 1935, cufflinks and waistcoat studs gained in volume with the appearance of the first baton cufflinks, the central part of which was mystery set with sapphires or rubies and framed by two convex forms set with diamonds. The Western aristocrats and Indian princes were particularly keen on these.

By the late 1930s, platinum was becoming scarcer in jewelry gradually being replaced by yellow gold. The latter allowed for pieces with more volume in a range of forms: gadrooned sticks and gold orbs with star-set sapphires or rubies, or precious ribbons of thin, twisted threads.

Everyday accessories

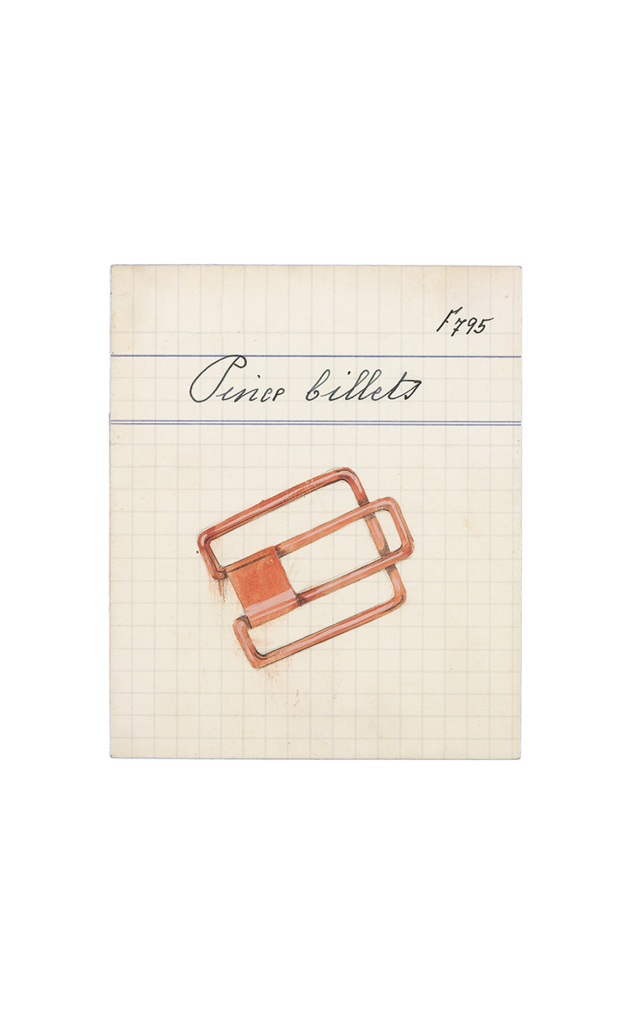

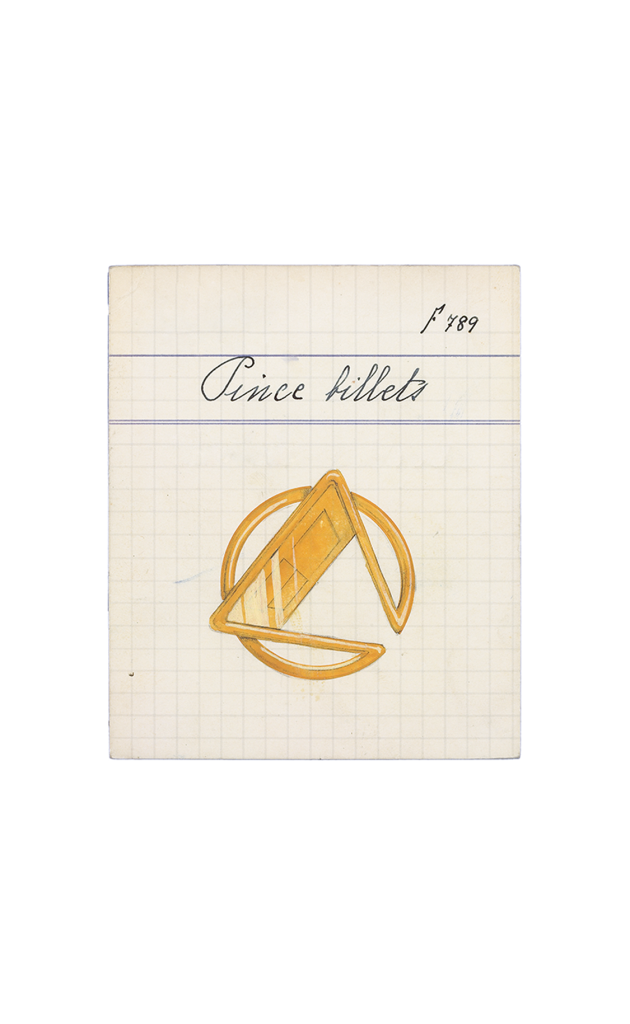

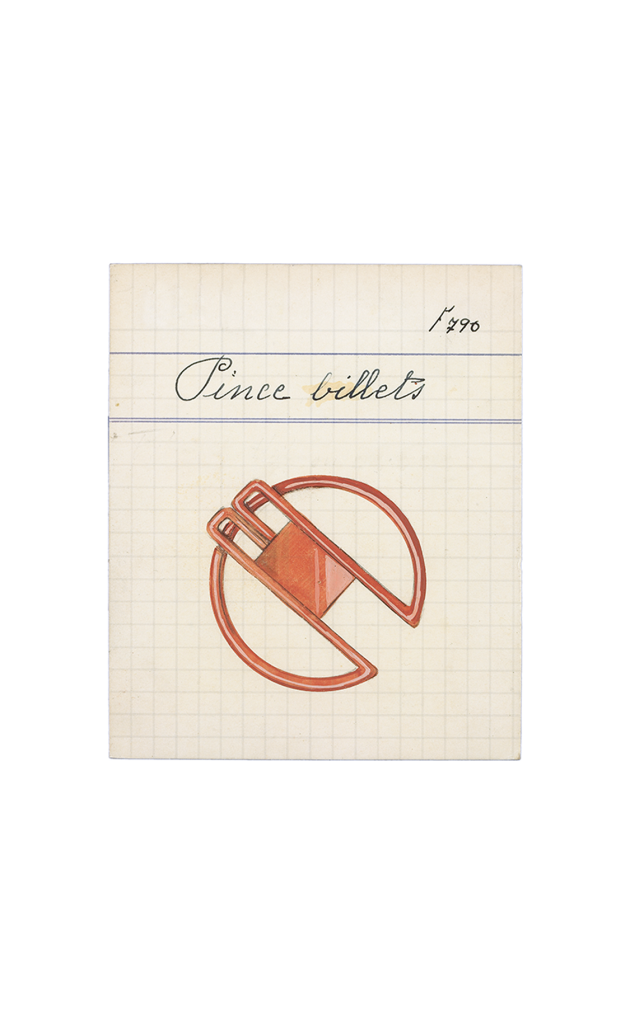

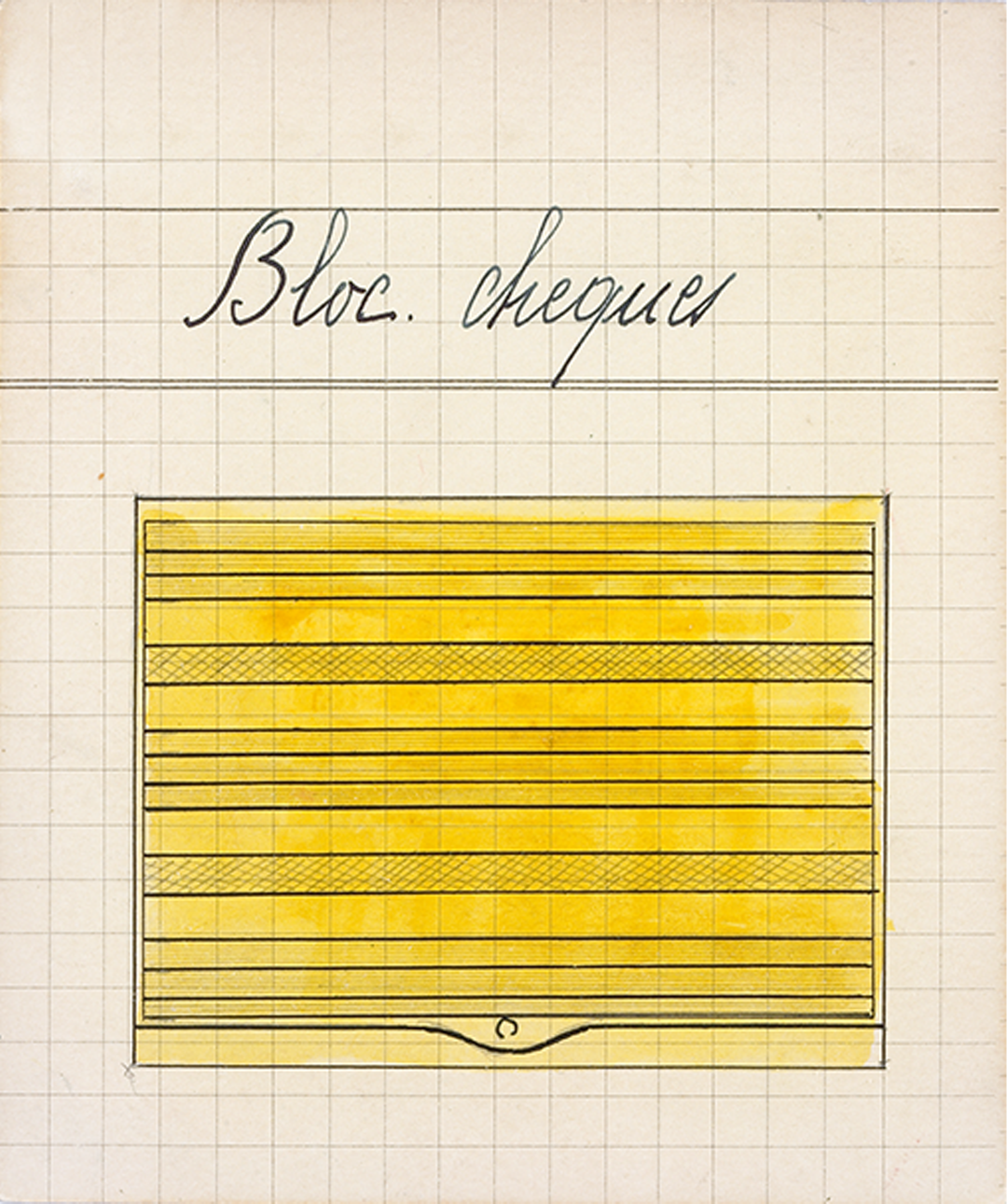

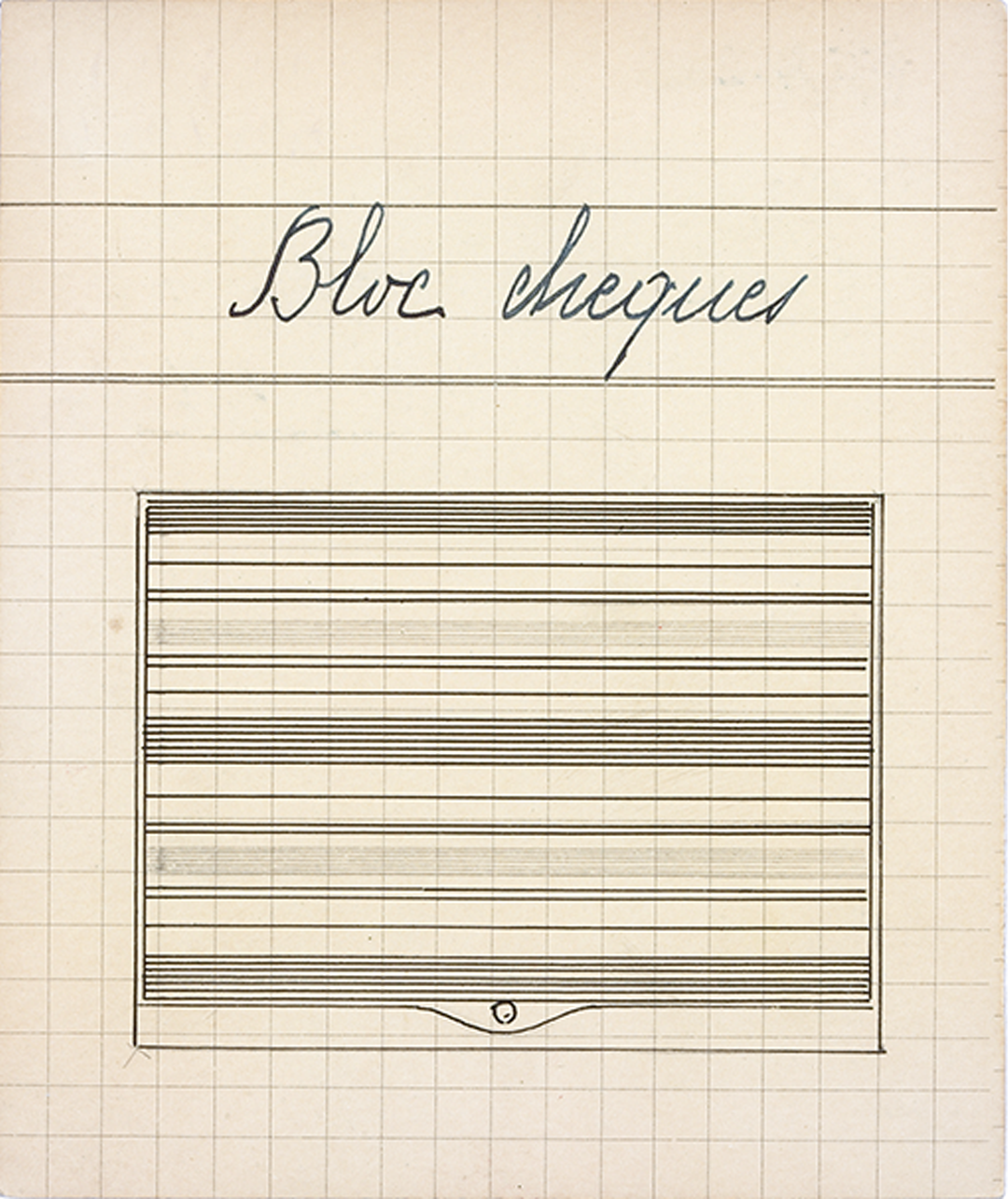

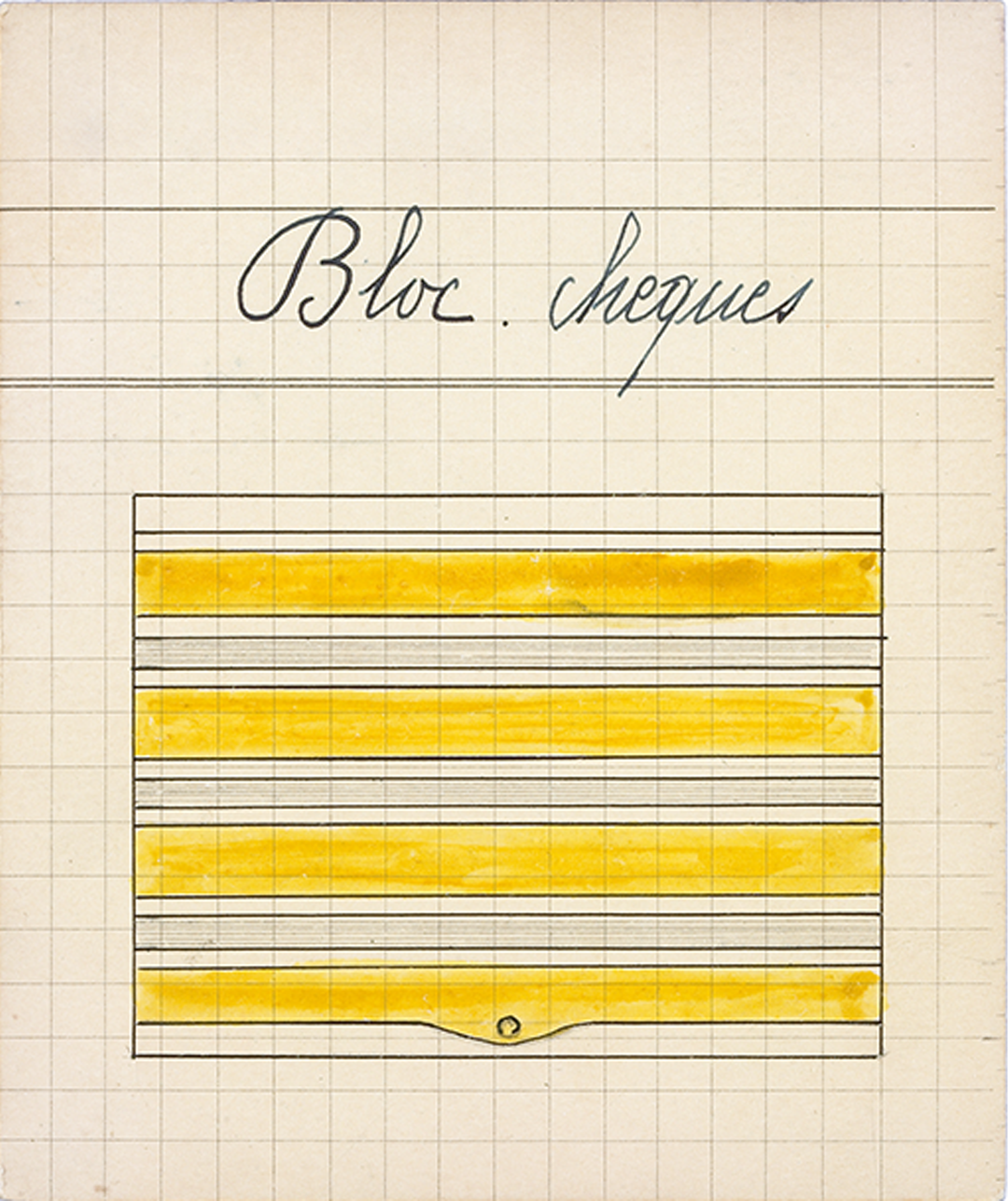

Van Cleef & Arpels created a wide variety of accessories relating to money and writing. These included a gold clip for holding banknotes, and a box for storing check books called a check pad, check case, or Vanarp,9Vanarp is an amalgam of Van and Arp, the first part of the two names Van Cleef and Arpels. in gold or guilloché silver.

CLIPS FOR HOLDING BANKNOTES

Pencil holders, mechanical pencils, dip pens, pencils, and pens were displayed in shop windows throughout the twentieth century, considered everyday objects by some, and accessories for special occasions by others. During the 1920s, these writing tools were decorated with Art Deco geometric motifs, thereafter being made in guilloché, barley grain, braided, or highly polished gold. The Patrimonial Collection contains an example of a 1928 gold and enamel pencil holder, whose outer tubing is a rotating calendar.

From the early 1950s, the back pages of the Maison’s catalogs included sets combining beauty accessories for women— lip brushes and perfume containers—with fountain pens and cigarette holders. A 1951 catalog features one such set with an engraved yellow gold flower motif throughout, enhanced here and there with gems. A 1954 catalog carries the following text relating to the accessories displayed in its end pages: “The Van Cleef & Arpels boutique is the modern solution to the problem of choosing a valuable, tasteful object. It is the expression of the most refined taste. Its creations, at carefully considered prices, are beautiful gifts enhanced by a prestigious signature.”

Set of beauty and writing accessories

Accessories for smokers

From the 1920s, Van Cleef & Arpels also excelled in the creation of accessories for smokers: cigarette cases, cigarette holders, cigar boxes, lighters, and ashtrays. The latter were particularly influenced by Art Deco and Modernism in terms of decoration and form. Their simplified, stylized lines were enhanced by the choice of materials, such as opaque lacquers and onyx, while the lively color contrasts reinforced their visual impact. An example of this is an ashtray in the Patrimonial Collection dating from around 1929, with a gray-veined agate bowl resting on a base composed of jade and agate disks. This stepped base is emphasized by a row of orange coral beads interspersed with yellow gold motifs.

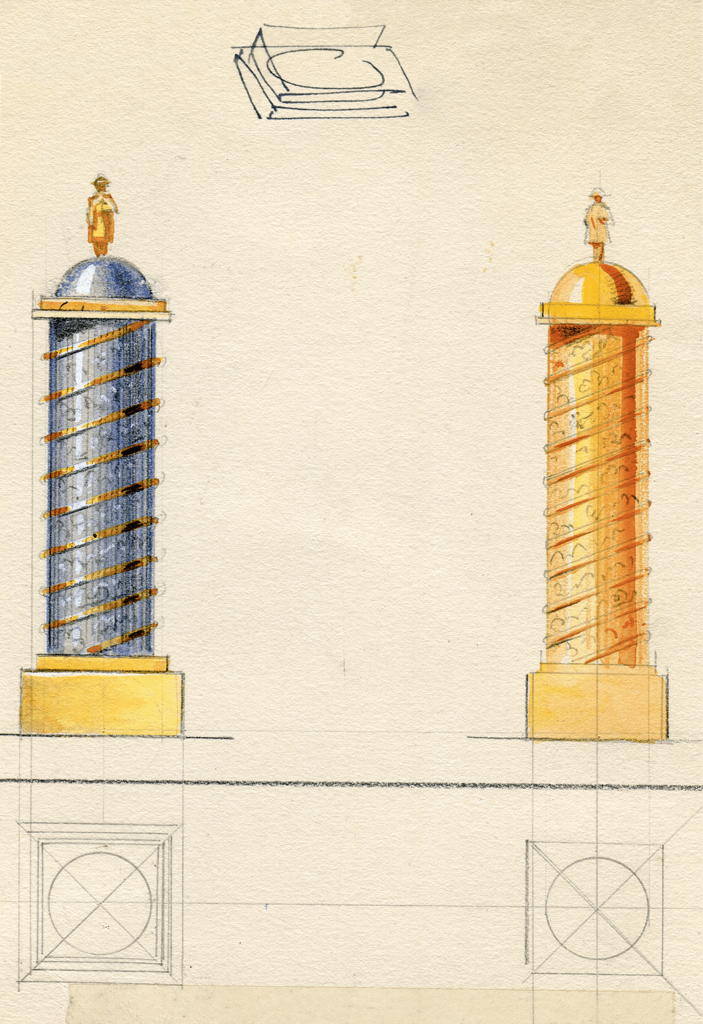

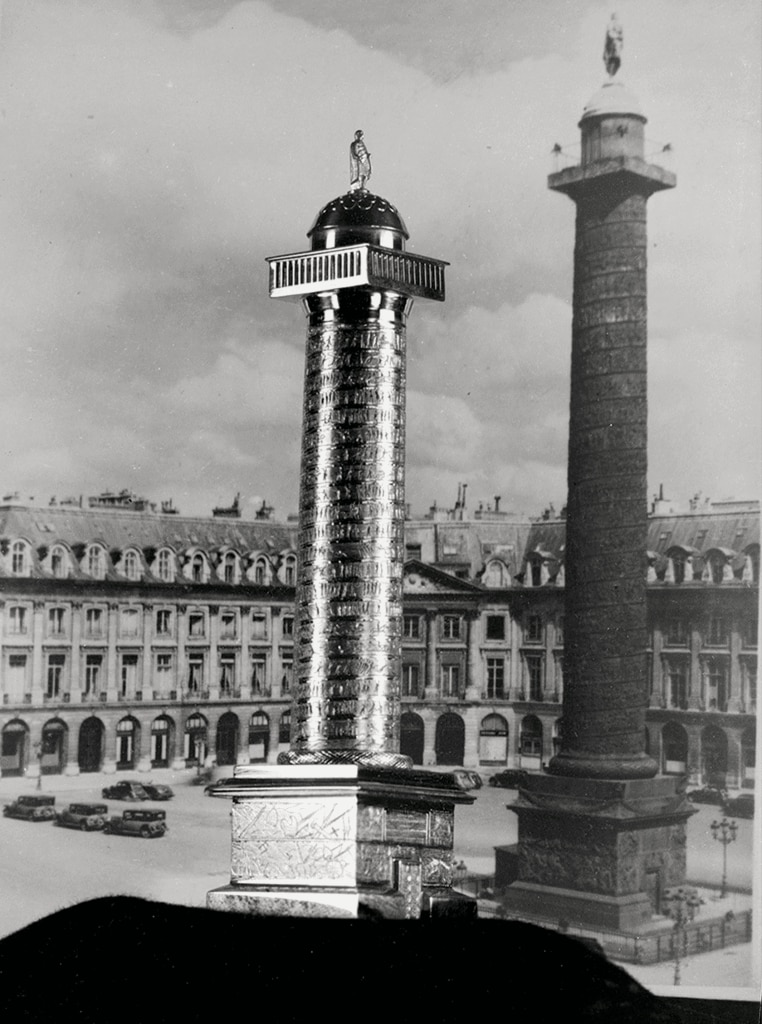

Within the same field, a 1950 table lighter displays Van Cleef & Arpels’ taste for figurative decoration evoking Paris, the Maison’s birthplace, and the Vendôme Column, the emblem of the square housing its boutique.

Nécessaires in the 1920s

Beauty accessories in the form of powder compacts and nécessaires, known as vanity cases in the United States, were produced to accompany the gaiety of the Roaring Twenties. Nécessaires were small precious purses that became indispensable for modern, fashion- able women. They were available in different shapes, usually rectangular or square, in small dimensions (approximately 4 cm high, 6 cm wide and 3 cm deep), and contained the essentials for a woman to refresh her makeup: a mirror, and compartments for powder and lipstick. A retractable watch could be nestled in the spine, enabling the time to be glimpsed discreetly.

Several examples in the Patrimonial Collection, dating from 1923 to 1925, are cylindrical in form and inspired by Japanese inrōs. These small, lavish boxes composed of stacked compartments, worn exclusively by Japanese men, were anchored to the upper part of a kimono belt using a counterweight called a netsuke.

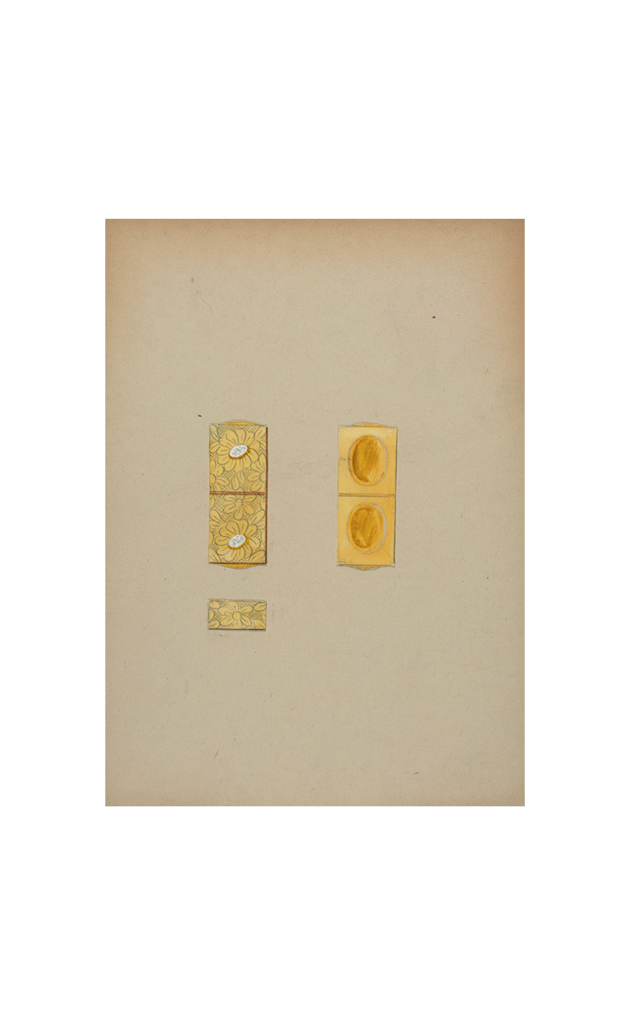

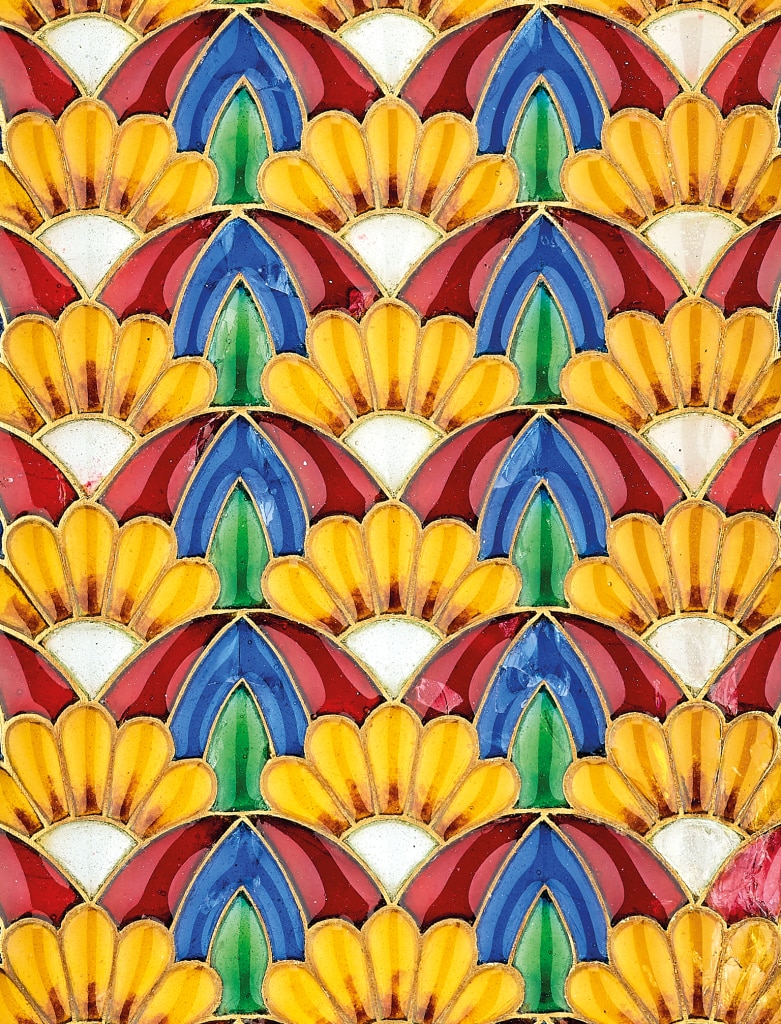

DRAWINGS OF NÉCESSAIRES

The decoration of Van Cleef & Arpels’ nécessaires ranged from sober to lavish, and illustrated a taste for Far Eastern and Persian art. The possibilities were infinite, from surfaces entirely covered with black lacquer dotted with the odd rose-cut diamond to lakeside scenes in ornamental stone or multi-colored mother-of-pearl inlay10Vladimir Makovsky (1884– 1966), a painter descended from a family of Russian painters settled in France, was particularly renowned for this ornamental and organic stone inlay work. Inspired by medieval history, as well as Chinese, Japanese, and Persian art, he worked for many different jewelers during the Art Deco period. framed with an enameled line. A good example is the jade nécessaire dating from 1925, whose lid of which features a house on stilts, beside a lake surrounded by mountains. With its play of asymmetry, and solid and empty space, the overall composition recalls the principles of Chinese and Japanese landscape painting. The multicolored brilliance of some nécessaires also harks back to the lively colors of the sets created for the Ballets Russes, very much in vogue in the French capital from 1909.

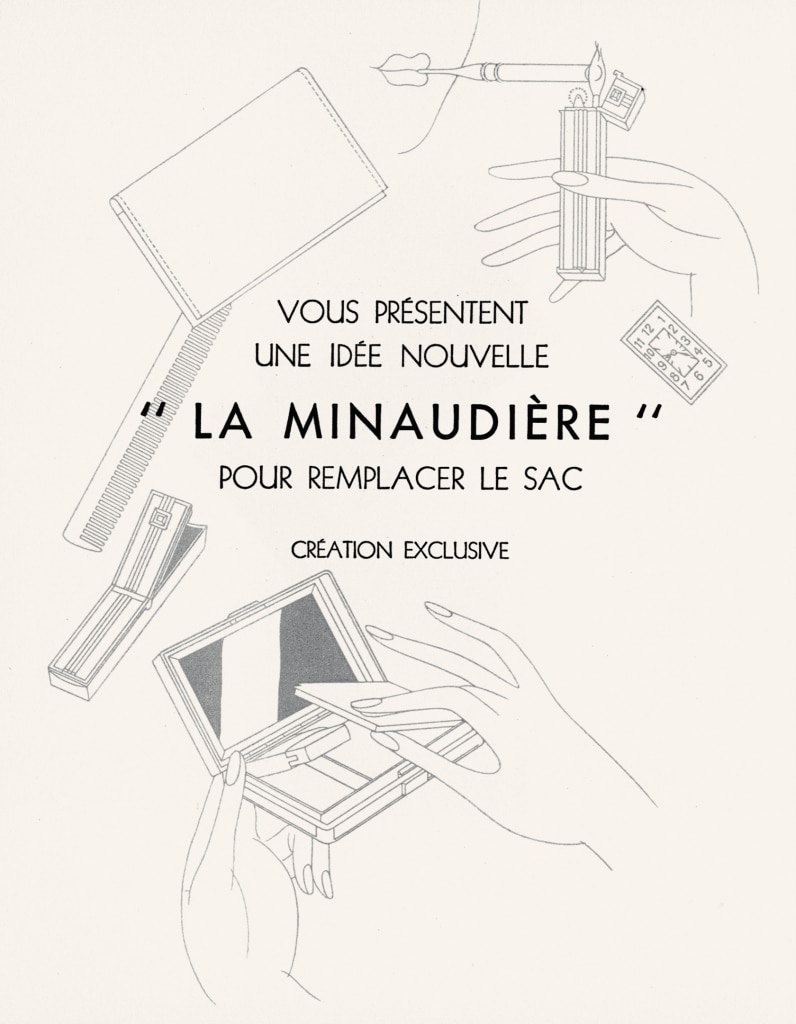

the Minaudière

As lifestyles evolved, so too did fashion accessories, adapting to these changes over time. A particularly notable example of this in the 1930s was the Minaudière.

Minaudière

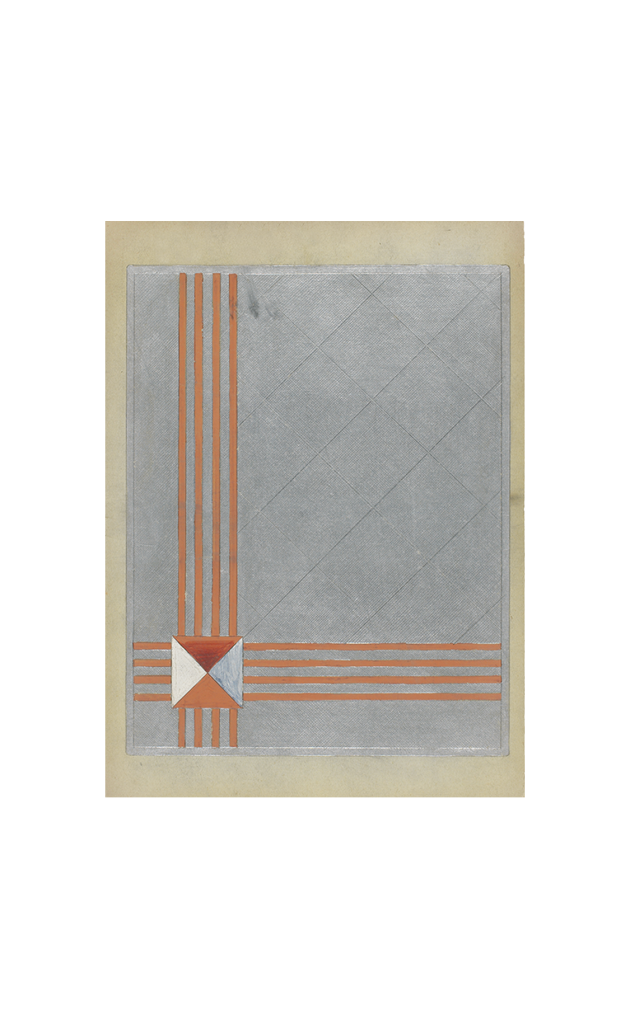

It emerged in an era given over to the cult of speed, and reflected the dictates of functionalism. The automobile was a leading invention of the industrial era and strongly influenced the design of accessories connected to it. Passengers’ small flat purses are seen as the ancestors of our present-day purses. Despite the Wall Street Crash of 1929, the 1930s was a decade of intense creativity and technical innovation for Van Cleef & Arpels. Renée Puissant, the only daughter of Estelle Arpels and Alfred Van Cleef, assumed the role of artistic director in 1926 and, over the course of the following decade, together with the talented designer René Sim Lacaze, formed an emblematic creative partnership. In the late 1920s,11The 1929 Salon d’Automne introduced the notion of spatial rationalization, across its 100 square meter surface, thanks to the work of well-known artists such as Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret, and Charlotte Perriand who were interested in interior fittings and lifestyles. and early 1930s a desire to combine the beautiful with the practical persisted. Advocating design that was both esthetic and useful for humankind, Charlotte Perriand12Together with other avant-garde artists, Charlotte Perriand (1903–1999), a graduate of the Union centrale des arts décoratifs in 1925, was a major figure of French architecture, design, and photography. She broke with tradition and fought against academicism, defending the use of new materials like metal. considered “finding the right subject” to be essential—for her, the subject was not the object, it was the user. It was within this context that Van Cleef & Arpels registered an initial patent referring to a “box-nécessaire” on July 25, 1933. This object was to be named “Minaudière” the following year by the Maison,13The word Minaudière echoed the name of the château that Alfred Van Cleef and his wife Estelle had owned since the 1920s, in the Yvelines at Flins-sur-Seine, where they hosted many parties. the new term being registered on January 18, 1934, in order to protect it.

An alternative to the bag

The “vanity box” or “clean, bare metallic box without handles,” as it was described in an article in Vogue Paris in 1935, was an object that was both precious and functional, enabling women to maintain their appearance. According to the oral tradition of the Arpels family, Charles Arpels, Alfred’s brother-in-law, was the one who invented it after noticing Florence Jay Gould, the wife of an American philanthropist and businessman, stuff all her beauty products into a metal box for Lucky Strike cigarettes. According to the newspapers of the time, this creation became famous as a “new idea, that of replacing the purse.”14André de Jonquière, “Le bijou et la mode,” Femina (January 1933): n.p.

This form, combining two accessories, a purse and a cigarette case, was humorously described in the text and drawings accompanying it in one of the Maison’s catalogs around 1933. The word “complexity” was associated with a purse, while “simplicity” described the Minaudière.

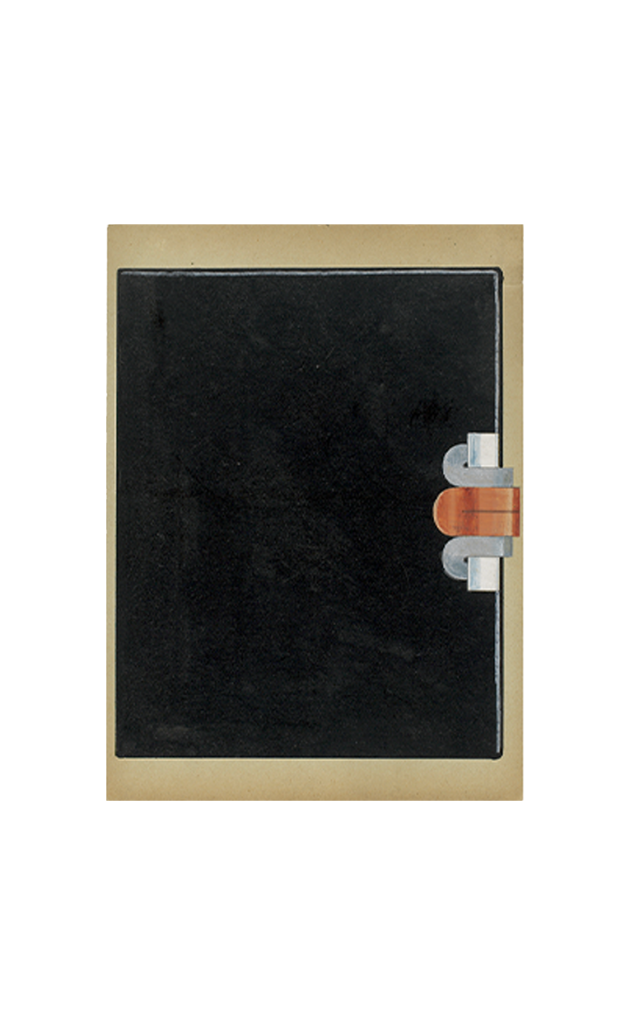

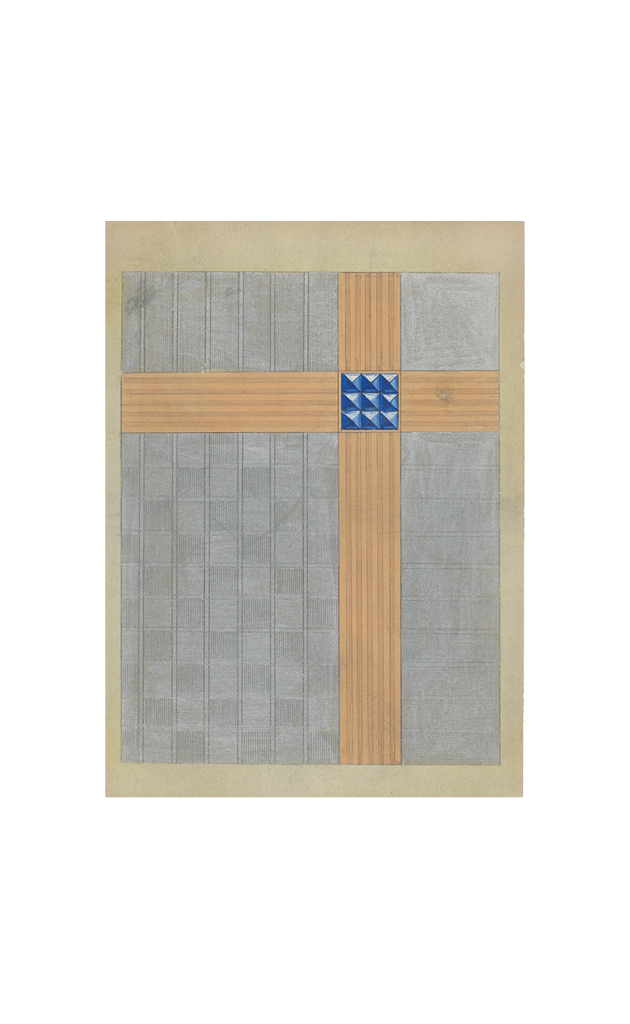

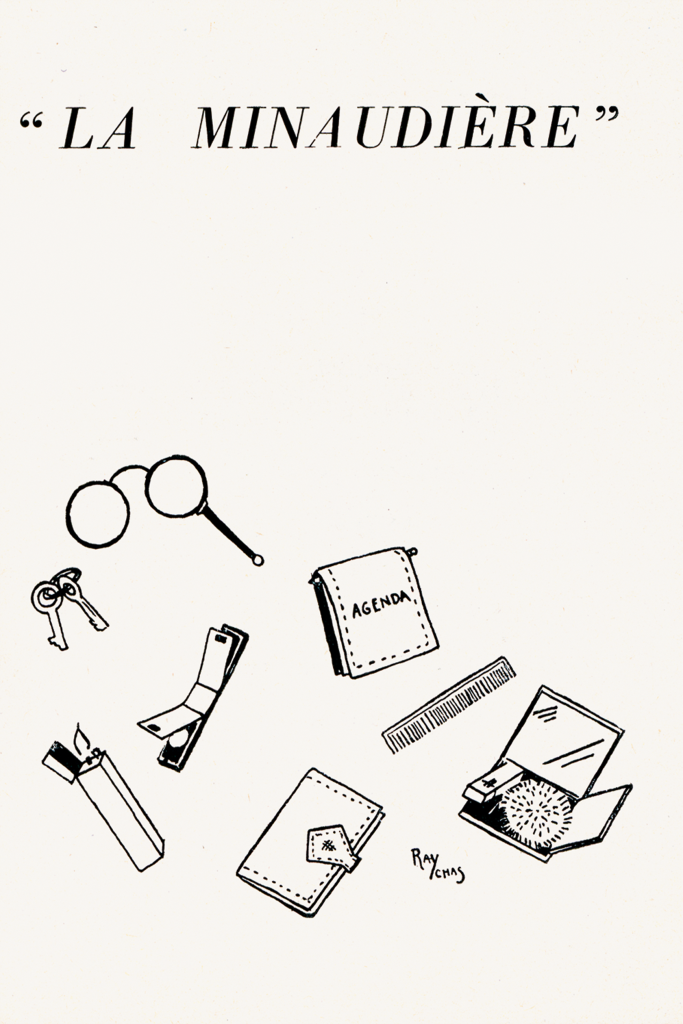

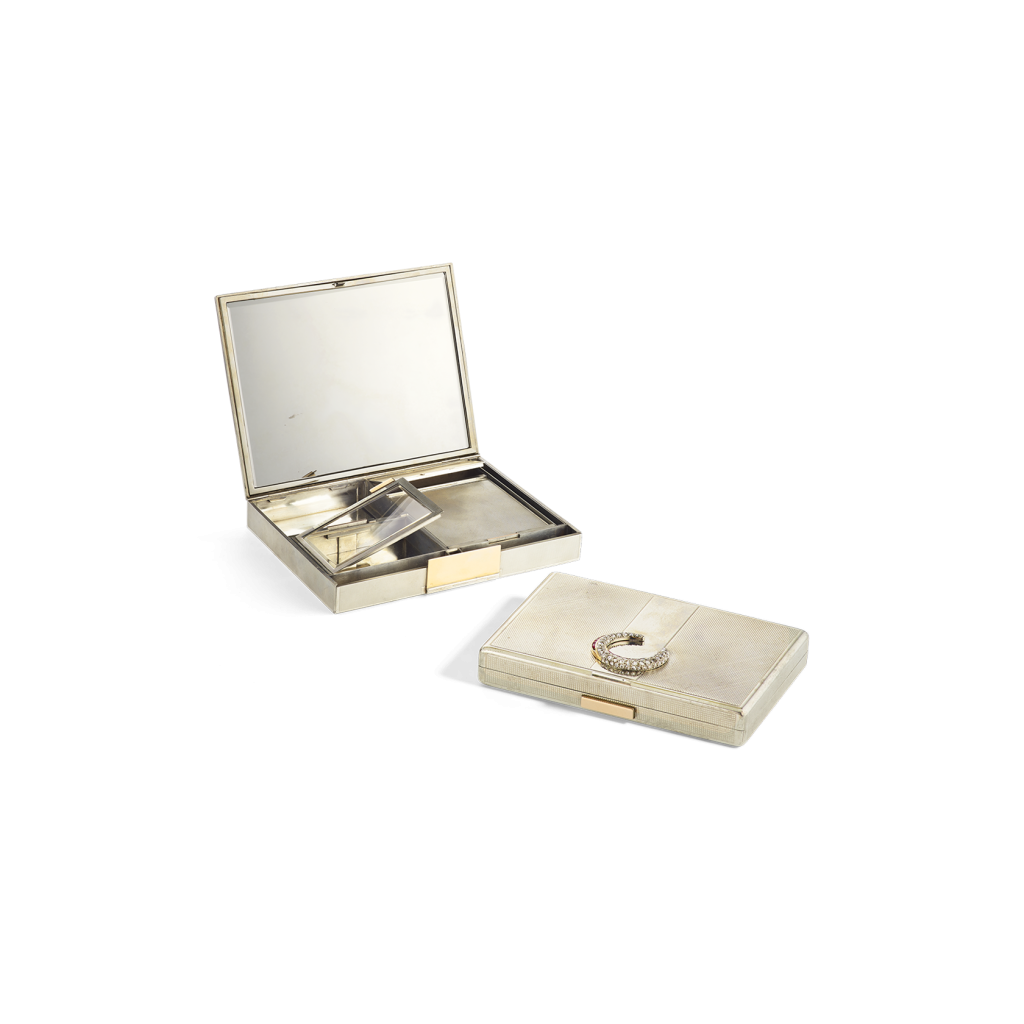

The latter was made of gold covered with black lacquer or of styptor,15The trademark “Styptor”, no. 281292, was registered on June 18, 1932, for a new alloy developed by the Maison made from less expensive common metals (including aluminum). Belonging to the nickel silver family, this new metal ranged from grayish to yellowish depending on the percentage of nickel and copper used. Like osmior, styptor was particularly used for making boxes, clocks, and “drawer-watches” (a box hidden within a setting that is frequently quadrangular, with notches to enable a drawer containing a watch module to be slid open or closed). an alloy developed to imitate platinum at lower cost, its solid form thus resolving the “[inelegant] silhouette [of a purse that] becomes misshapen and bulky” when too full. Similarly, its compartmentalized interior also resolved the “clutter of all those things no woman would ever agree to do without.” This attention to outline and to the essential was in keeping with the functionalist movement that had emerged a few years earlier within architecture and furniture. Designed to satisfy the needs of its owner, every element had its correct place, as in a puzzle: containers for powder, blush, pills, lipstick, cigarettes, lighter, and even a dance card and pen. A long thin space to fit a comb with a metal frame matching that of the Minaudière itself. Sometimes perfume bottles or lipstick containers concealed a watch in their lid, while another watchmaking dial is hidden on the outside of the box.

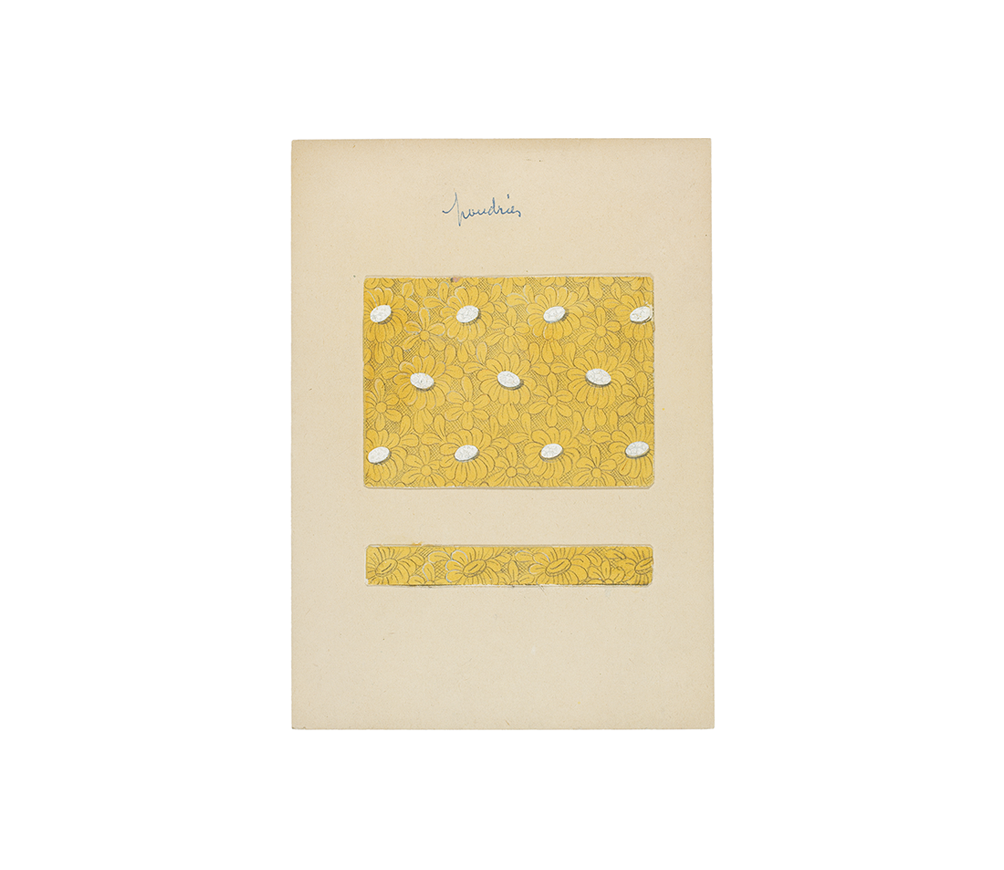

WORKSHOP CARDS OF MINAUDIÈRES

How to wear the Minaudière

Minaudières were carried in the hand like books but could also be slipped into a custom-made fabric purse with two handles, one looped over the other, allowing this small, luxurious box to be worn around the wrist or elbow. The outer fabric of these rigid, custom-made purses sometimes presented a three-dimensional, tone-on-tone version of the design seen on the lid of the box, or had carefully positioned holes that allowed the motifs adorning these lids to show through. This was the case for a styptor Minaudière made in 1934, now in the Patrimonial Collection, decorated with a platinum circle pavé-set with rose-cut diamonds and set with calibrated rubies—a trompe-l’œil (version) of a Circle clip—and enhanced with a strip of mirror-polished styptor that stands out against the engine-turned background. The black fabric purse that accompanies it has a round hole that allows the motif to show through.

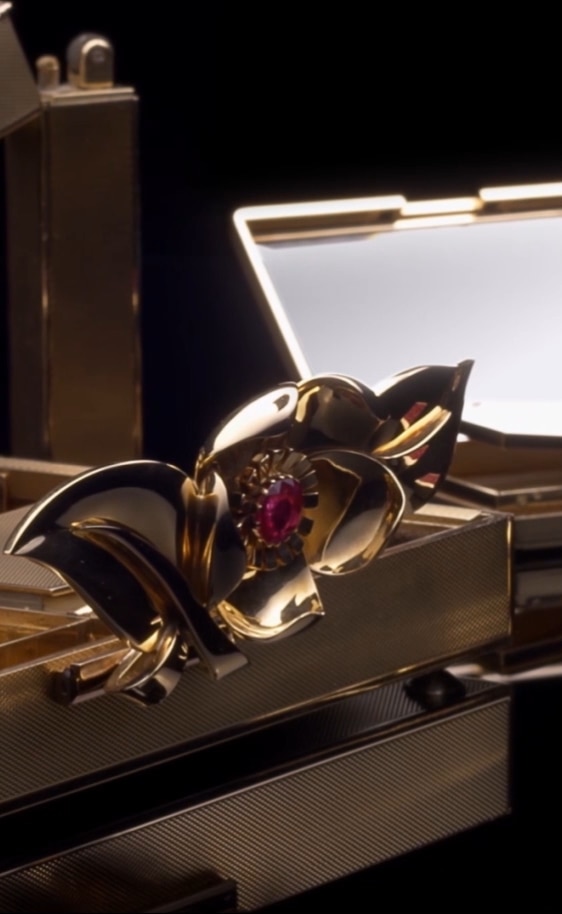

The clasps and decorations of the Minaudières

The clasps of certain Minaudières could be detached and worn as brooches, in keeping with the Maison’s taste for transformable ornaments. One such was the wild rose clasp of a 1938 Minaudière in the Patrimonial Collection. Numerous workshop cards dedicated to these detachable elements illustrate Van Cleef & Arpels’ creativity in this field. The Maison sought inspiration from fashion, with coiled platinum and diamond ribbons; from nature, with a wide range of flowers and leaves; and from Art Deco forms favoring outline and stylized motifs.

Minaudière

Patterns on the lids of 1940s Minaudières echoed those found on powder compacts and cigarette cases of the same period, with three-dimensional figurative motifs (animals and figures) that stood out against the engraved gold backgrounds. This ornamentation features scenes from nature teeming with details—of ducks swimming among a lake or families of birds perched on the foliage of trees—as well as the taste for historical revivalism.

The latter is seen in the 1942 Minaudière made for the Maharaja of Baroda—a jewelry version of Franz-Xaver Winterhalter’s 1855 painting of Empress Eugénie surrounded by her ladies in waiting, a work currently held by the Musée national du Château de Compiègne.

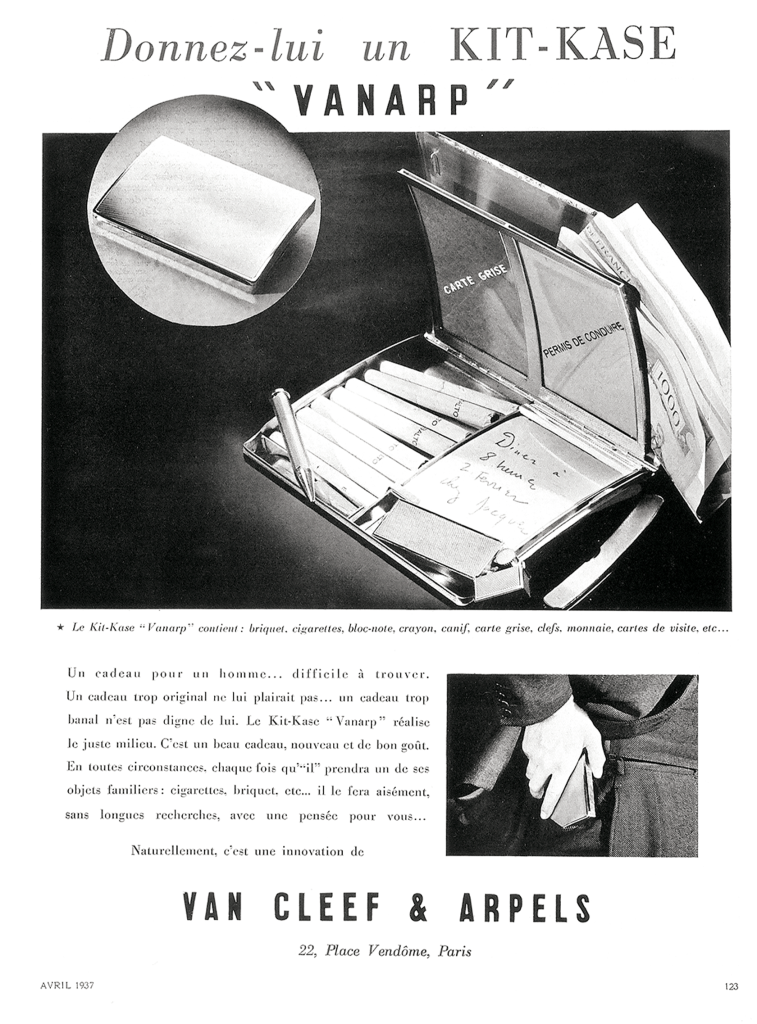

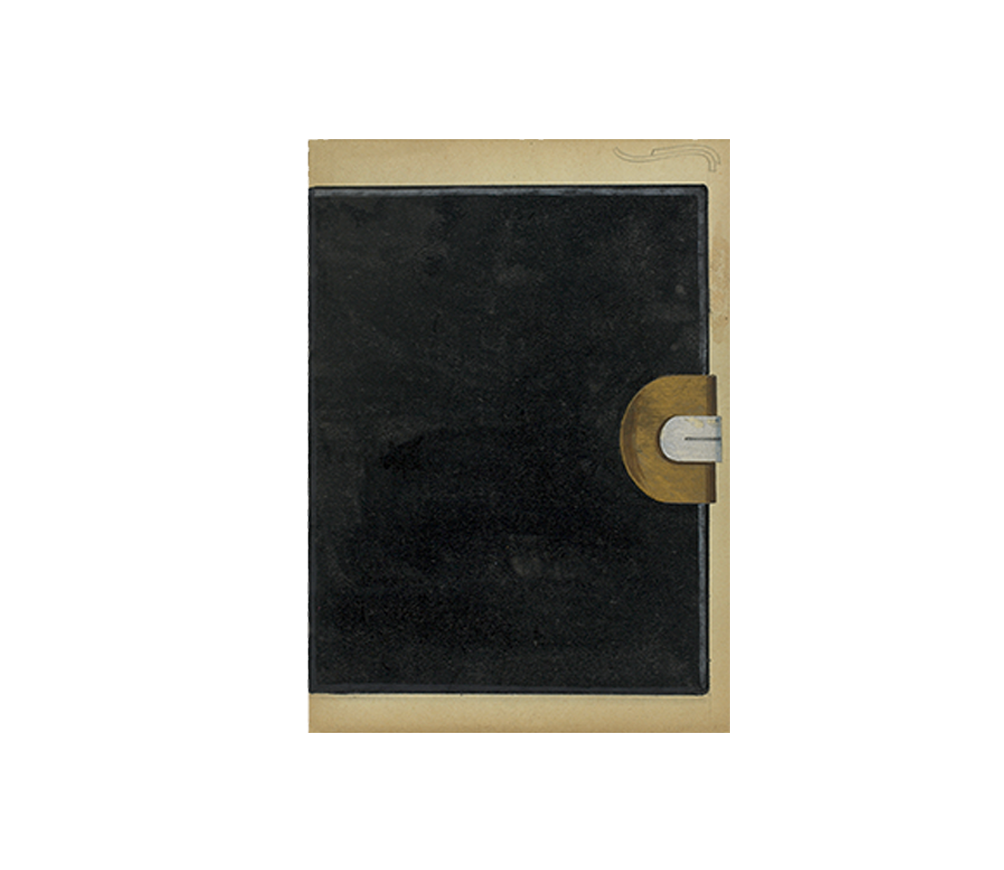

The Vanarp : Minaudière for men

While the Minaudière tended to be a woman’s preserve, some examples were aimed at men. The above-mentioned Vanarp Kit-Kase had different compartments for storing cigarettes, lighter, notepad, pen, and mirror, and a sort of gusset pocket for papers. As with the Minaudière, Van Cleef & Arpels advertised the practical side of the Vanarp for the customer: “Whenever he takes one of his familiar items […], he will be able to do so easily, without spending ages looking for it.” The Minaudière, a pioneering accessory of the 1930s and 1940s, was revived throughout the three subsequent decades in previously unseen forms such as the polylobed example in the shape of a flower. Some even reintroduced “good-luck” wood as their main material.

Technical innovation and aesthetics for everyday use

Van Cleef & Arpels’ precious objects, be they functional or decorative, have illustrated the Maison’s technical and stylistic advances throughout the decades. The attention paid to the drawings, the jeweler’s savoir-faire, and the rigorous gemstone selection can be found in all the object’s details. As part of the Van Cleef & Arpels’ jewelry tradition right up to the present day, these precious objects and accessories have led the Maison to explore a wider range of materials, techniques, and skills for its esthetically appreciative clientele.