Solène Taquet et Cécile Lugand

When Van Cleef & Arpels was founded in 1906, nature was a subject of great interest to the art world as a whole. Sensitive to the esthetic context of the period, the Maison, quickly demonstrated a pronounced astuteness in its use of flora and fauna motifs…

Nature is a subject found throughout the entire history of art since antiquity and an inexhaustible source of inspiration for artists, all of whom have tried to defy the ephemeral beauty of flowers. Naturalist jewelry has a considerable advantage in this respect, for it never wilts. These motifs, when used in jewelry, were also sometimes charged with meaning that could be highly personal, symbolic, or sentimental. Nature as portrayed by jewelers was alternatively idealized, recreated, and glorified, as its representation gradually evolved towards greater realism. This evolution reached its height in the nineteenth century with the emergence of technical innovations that allowed for new scientific studies. Botanical research the exploration of the seabed and discoveries of new animal, vegetal, and mineral species led to a thorough revolution of the natural sciences and the uncovering of unexpected riches. These discoveries inspired and excited artists and jewelers alike. During the nineteenth century, flowers in jewelry assumed many different forms that changed in accordance with artistic currents. After being endowed with a symbolic language during the Romantic period,1Romantic jewelry, popular from around 1820, was typified by a love of the picturesque and heightened sentiments. These pieces therefore became coded messages referring to loved ones, with the floral motifs being chosen for their symbolism rather than their esthetic value. inspired by the eighteenth century, and sometimes worn in bouquet form on stomachers during the Second Empire, they became organic and fanciful with Art Nouveau,2From the 1880s, some artists rejected the newly industrialized production and prevailing historical revivalism, preferring to restore art’s organic essence. Following on from Japan’s opening up to the world, works that provided a different perception of nature began to reach Europe. Flora and fauna were seen in motifs that were both simple and elegant and were to inspire the West. This ornamental repertory was reinterpreted in sinuous, delicate curves reproduced in materials that had rarely been seen in Europe before (like gemstones, horn, tortoiseshell, ivory, etc.). from 1890 onwards. Flowers remained equally important in twentieth-century art, omnipresent in painting, architecture, and the decorative arts, while retaining pride of place in the jewelry arts.

Naturalism and movement

Following on from this nineteenth century jewelry tradition and in keeping with con- temporary artists’ interest in nature,3The Maison’s first shop, at 22 Place Vendôme in Paris, was situated next to that of René Lalique, at number 24. At that time, Lalique was considered Art Nouveau’s most famous representative, and his work may have given Van Cleef & Arpels a distinct taste for nature, notably for flora. For more on this subject, see Yvonne Brunhammer, René Lalique: inventeur du bijou moderne (Paris: Gallimard, 2007) and Yvonne Brunhammer, ed., René Lalique: Exceptional Jewellery 1890-1912, [exhib. cat.] (Milan: Skira, 2007). Van Cleef & Arpels initially adopted a faithful interpretation of flora—a naturalist vein that it would pursue throughout its production over time. Following the great aesthetic currents of the twentieth century, the Maison nevertheless developed a renewed vision in parallel, be it stylized, modern, pared-down, avant-garde… Indeed, nature as depicted by Van Cleef & Arpels was sometimes a hybrid expression of several sources of inspiration. Throughout its numerous transpositions, however, one feature remained constant: a sense of movement. Flora and fauna were endlessly depicted as lively and graceful, tirelessly unfurled in extremely solid materials, thanks to the daring savoir-faire and technical innovations that were to become a hallmark of the Maison.

Pieces inspired from the eighteenth century

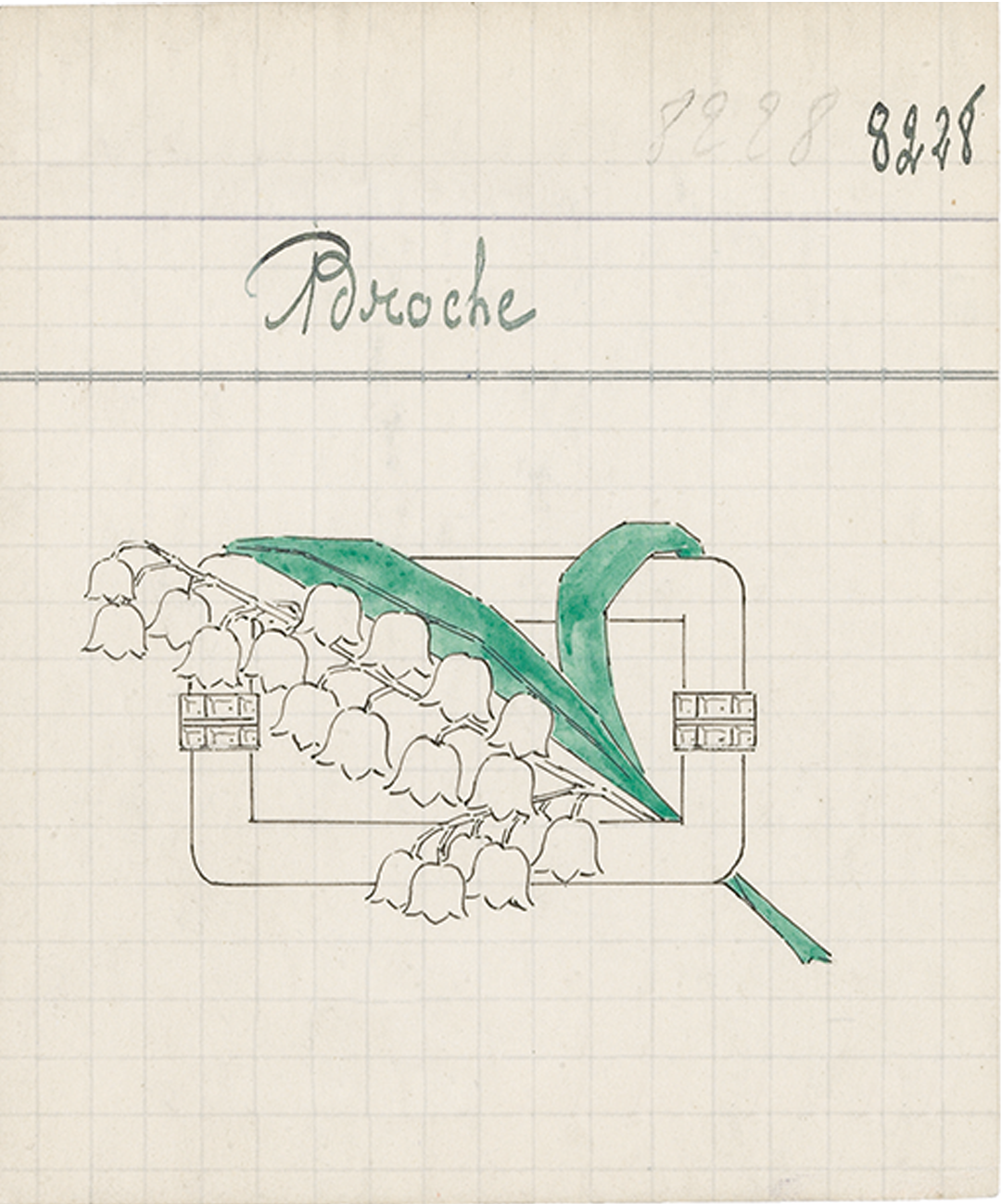

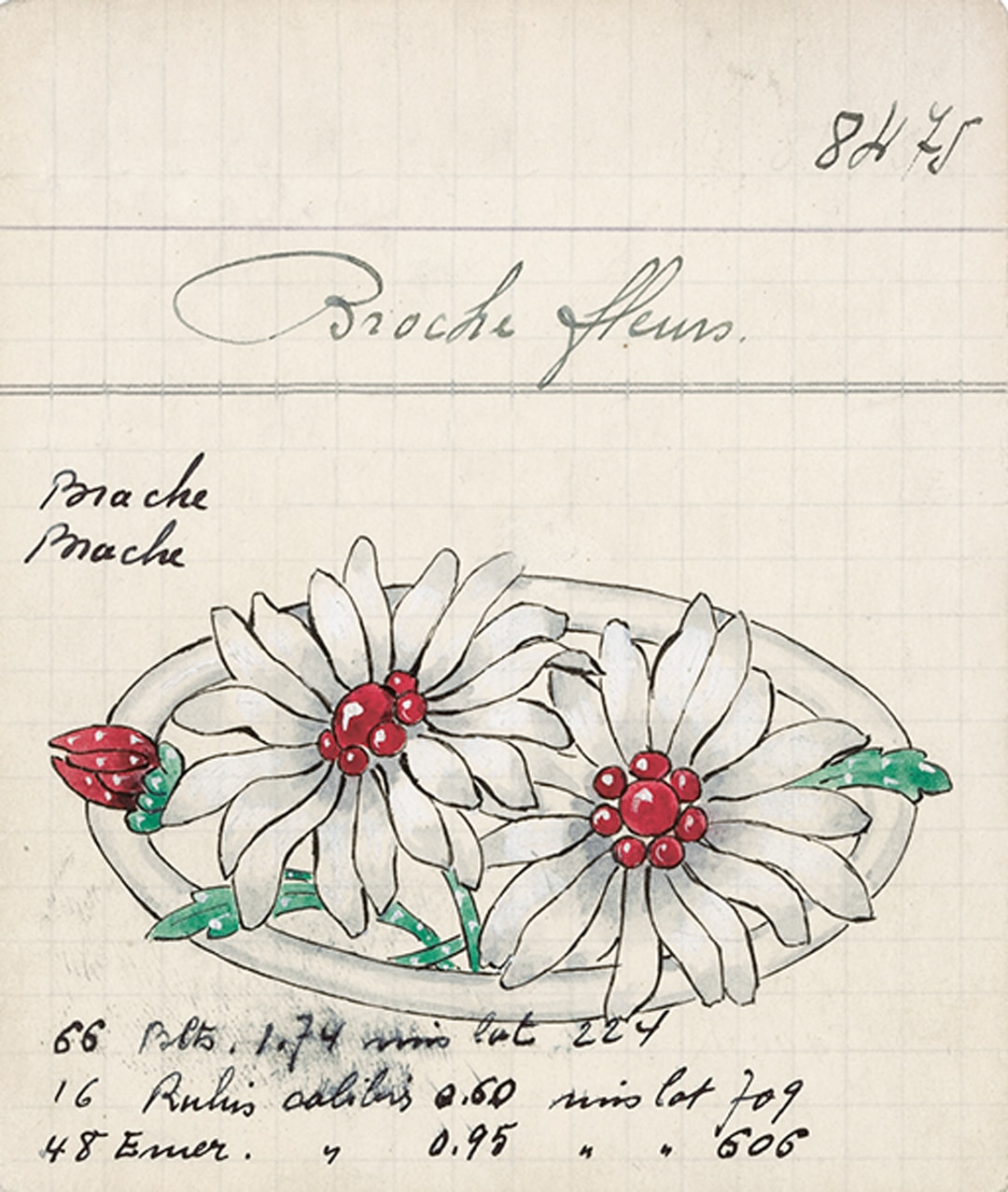

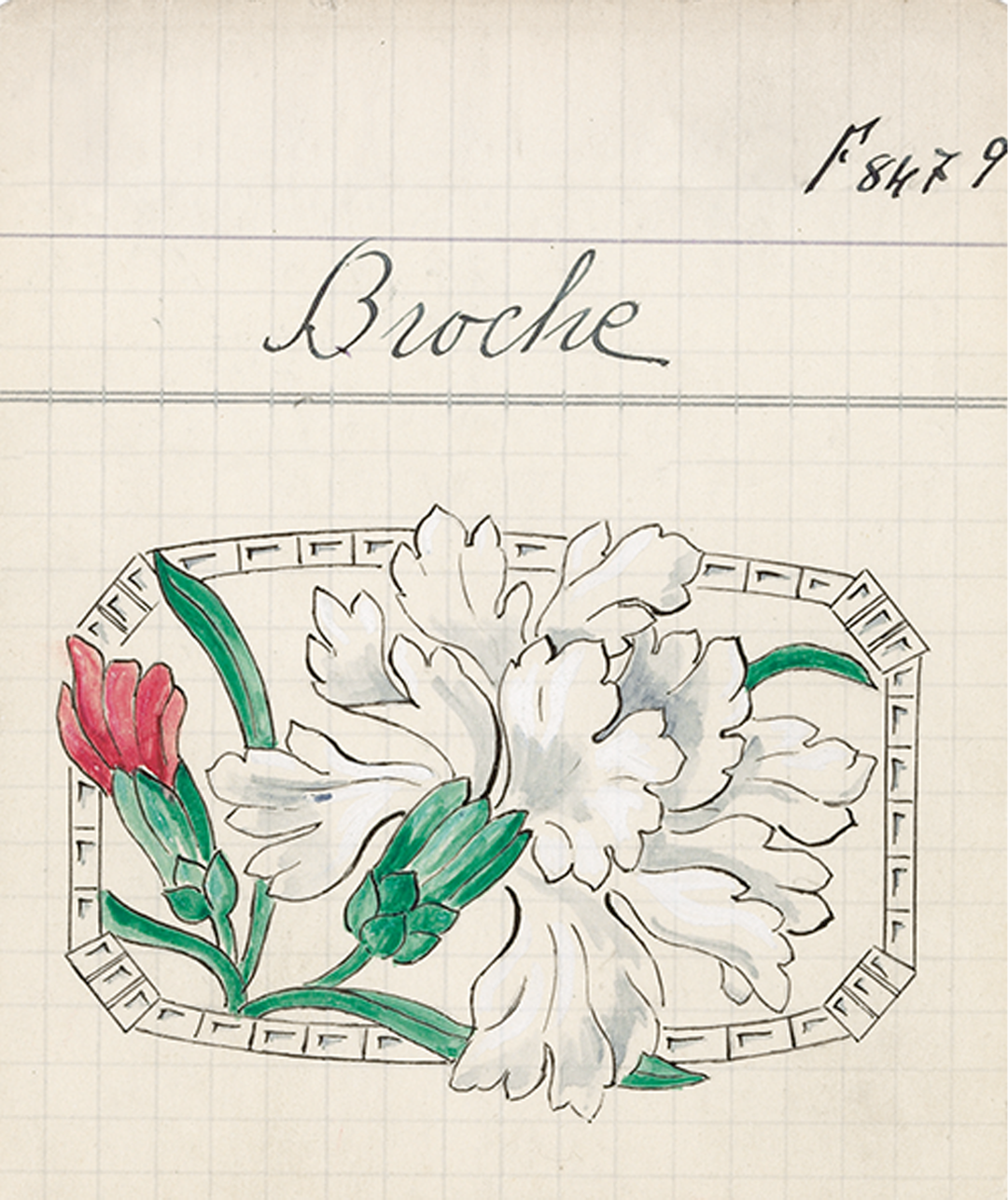

Van Cleef & Arpels’ taste for nature was visible from the outset, as its archives show. In 1907, for example, they mention a bracelet adorned with clovers and a diamond daisy brooch.4Sales ledger, 1906–1910. Paris, Van Cleef & Arpels Archives. The Maison created pieces in the style inherited from nineteenth-century jewelry, rooted as it was in the Belle Époque esthetic. Through detailed study of the model in sketches and drawings, its jewelry tended to be particularly naturalistic in design, reminiscent of Second Empire pieces, themselves inspired by the eighteenth century. They were characterized by their lightness, since diamonds mounted on platinum5Platinum is a grayish-white precious metal that is denser than gold and silver, ductile, extremely malleable, and unaltered by air, thus enabling immensely delicate pieces to be made. Rarely seen until then, indeed unknown to some, its use spread as a result of the work carried out by Sainte-Claire Deville and Debray on its fusion in 1860. The discovery of diamond mines in South Africa at this time encouraged the large-scale importation of diamonds to Europe. This explains why jewelry at the turn of the twentieth century was referred to as “white diamond jewelry,” with previously unseen combinations of platinum, diamonds, and pearls producing particularly sophisticated naturalistic pieces. were all the rage. Given that the metal was virtually invisible, the gems of unsurpassed brilliance, radiance, and whiteness appeared as though suspended in thin air.

Historicist reinterpretations

In the 1920s, historical revivalism persisted. Like giardinetti jewelry fashionable in the eighteenth century,6Ring, eighteenth century, diamonds, emeralds, and rubies, European. Paris, Musée du Louvre, no. inv. ECL15489. single flowers or bouquets, often of recognizable species, blossomed freely or within frames. The product card for a Carnation brooch dating from 1927 recalls an important artistic custom, namely of using carnations for their symbolism. They had been used in this way in the arts since antiquity, and were particularly prevalent in eighteenth-century jewelry.7Pendant in the form of a carnation, eighteenth century, silver, emeralds, almandine garnets, amethysts, and yellow sapphires, French. Paris, Musée des arts décoratifs, no. inv. 8822. Petals and leaves were depicted opening out freely, sometimes beyond the frame—proof of the Maison’s modernity and its quest to recreate nature as living and moving.

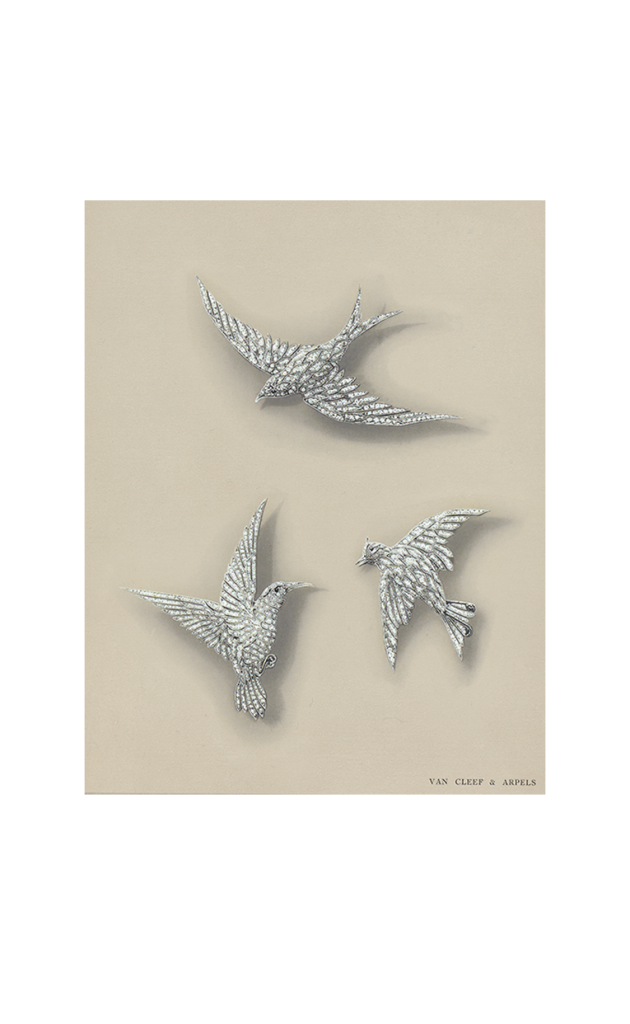

At the same time, seagulls, hummingbirds, swallows, and kingfishers featured on pins worn in women’s hair or on hats. This iconography might evoke the atmosphere of the seaside resorts that were very fashionable during the Belle Époque and where the Maison successively opened several boutiques between the 1910s and the 1920s. These birds, with their wings spread, also looked to nineteenth-century naturalism: the platinum enabled the detailed depiction of slender bodies in flight, as well as of feathers and feet in adroitly studied positions.

A universal nature

While the Maison displayed a particular attraction for distant civilizations, nature became universal: inspiration came from other horizons. Decoration from exotic repertories was especially observed on châtelaines, which had been fashionable in the eighteenth century.8Originally, the châtelaine was a piece of jewelry attached to a woman’s belt from which various small useful and decorative objects were hung: a watch, a purse, a seal, keys, a mirror, a rosary… (Châtelaine, late eighteenth century, gold, silver, steel, marcasite, enamel, and glass, French. Musée des arts décoratifs, Paris, no. inv. 24695). Following the revival of interest for the Rococo period, the châtelaine became the support for a watch dial, usually concealed on the back of its pendant form. A châtelaine watch dating from 1924, was decorated with a Chinese-inspired landscape that stood out against a black-lacquer background— an ancestral decoration technique of Asian origin —while in 1926, another portrayed a basket overflowing with flowers, fruit, and leaves in engraved stones, taken from Indian art. Some powder compacts and cigarette cases displayed vegetal motifs on their covers reminiscent of the Saz style,9The Saz style, ornamentation for ceramics developed in 1520 at the Ottoman court by the painter Shah Quli, was characterized by compositions combining long, saw-toothed leaves and flowers. For more on the subject, see: Sophie Makariou, ed., Les Arts de l’Islam au musée du Louvre (Paris: Louvre éditions / Hazan, 2012). or landscapes inspired by Asian seascapes.

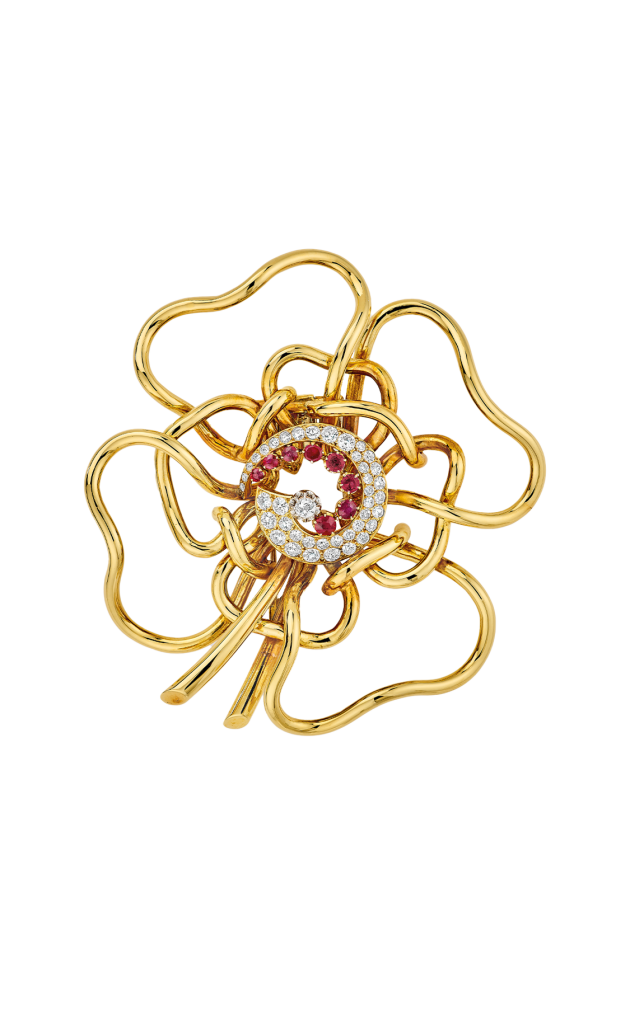

Brooches and clips, the preferred media for naturalist aesthetics

Clips from the late 1930s, composed of flowers that looked as though they had been freshly picked and tied with a precious ribbon, in turn recalled Rococo works from the eighteenth century. On the Bouquet of Violets clip, the detailed sculpture of the amethysts; the ethereal movement given to the whole piece, as if suspended; and the different nuances of the gems realistically conferred a sense of fragility to the petals.

As for a brooch dating from 1938, it referred to nineteenth-century botanical sketches in its detailed rendering of the petals and leaves.10For more on this subject, see Christian Bange, “Les botanistes français et la flore d’Europe au XIXe siècle”, Réseaux culturels européens: des constructions variées au fil du temps (Paris: Éditions du CTHS, 2003), 255–276. Pavé-set with round diamonds mounted on platinum, its curved contours, smooth or serrated, expressed freshness and vitality. The flower in the middle of the piece could sometimes be detached to be worn without its leaves, in keeping with the notion of transformability so dear by the Maison. As for watches, they had served as favored supports for the plant world since the late 1920s. Adorned with rinceaux of multi-colored gemstones depicting buttercups, camellias, and vine leaves, their dials were concealed thanks to ingenious mechanisms that enabled the wearer to glance at the time discreetly, in keeping with the social conventions of the time. The secret watch remained one of the Maison’s preferred ways of applying a decidedly naturalist vision of flora to watchmaking.

Romantic interpretations of the floral motif

This bucolic taste continued throughout the 1940s and 1950s. Powder compacts, cigarette cases, and Minaudières were covered with landscapes of the countryside, of lakesides and of the sea, engraved on yellow gold and enhanced with precious stones, as well as occasional lovebirds tweeting in the greenery beside a pond, as in The Lake powder compact. Other boxes had scatterings of daisies and primroses like mille-fleur tapestries, their petals reversed out on guilloché backgrounds.11A decorative technique that involved removing metal by engraving motifs with more or less straight lines of varying evenness. The lines making up this form of decoration are called guillochures, while the whole pattern obtained by the use of this technique forms the guillochis. The latter is sometimes left as is, but normally tends to be covered with a layer of translucent colored enamel to accentuate the effect of the engraved lines and their relief. This is referred to as guilloché enamel.

In keeping with this highly romantic interpretation of floral language, the Maison also applied naturalist decoration to its so-called sentimental jewelry. An article titled “Three budgets for engagement rings” written in 1956 featured a You and Me ring12A ring crowned with a bezel set with two ornaments, traditionally a diamond offset by a colored stone. It was particularly fashionable in the nineteenth century, and symbolizes an inseparable couple and requited love. designed by Van Cleef & Arpels. In place of the two traditional interlaced stones, the Maison substituted two asymmetrically set diamond clovers. What with Romantic and Rococo art, naturalistic depictions, and symbolic representations, these floral interpretations sometimes mingled to the point of merging.

The geometrization of nature

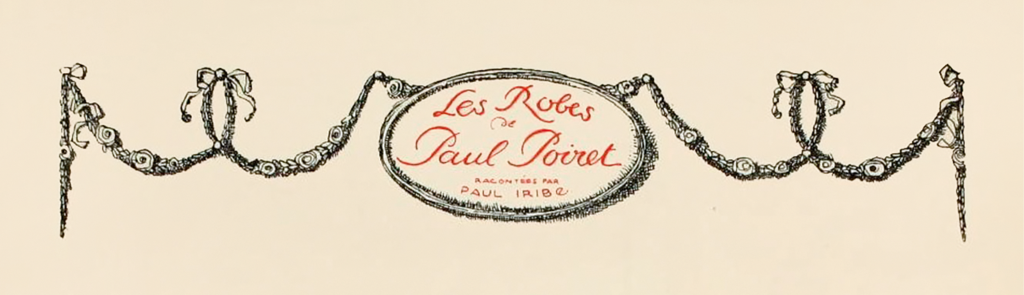

While revivalism may be seen throughout the Maison’s history, it has never been old-fashioned, for Van Cleef & Arpels has consistently kept up with the artistic currents of its time. As Art Deco gradually spread through all means of expression, the Maison adopted a more geometrical interpretation of nature. The “Iribe rose” was one of the most fashionable floral motifs during the 1920s. Created by the French designer and illustrator Paul Iribe in 1908, this stylized rose gradually made its way into all the arts, thanks in large part to the influence of couturier Paul Poiret. Architecture,13The facades of many buildings in Paris at this time were adorned with sculpted roses. One of the most significant examples outside the French capital is the Casino in Saint- Quentin, Picardy, which features the stylized rose throughout its molded cement facade. Designed by architect Adolphe Grisel in 1929, the building has known many incarnations, including theater, cinema, music hall, dance hall, and even reception hall. furniture,14Paul Poiret, Three-leaf Screen, circa 1912–1913. Paris, Musée d’Orsay, no. inv. OAO1692. fashion,15Paul Poiret, Evening Coat, circa 1912. New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, no. inv. 2009.300.1368. jewelry… they all featured it.

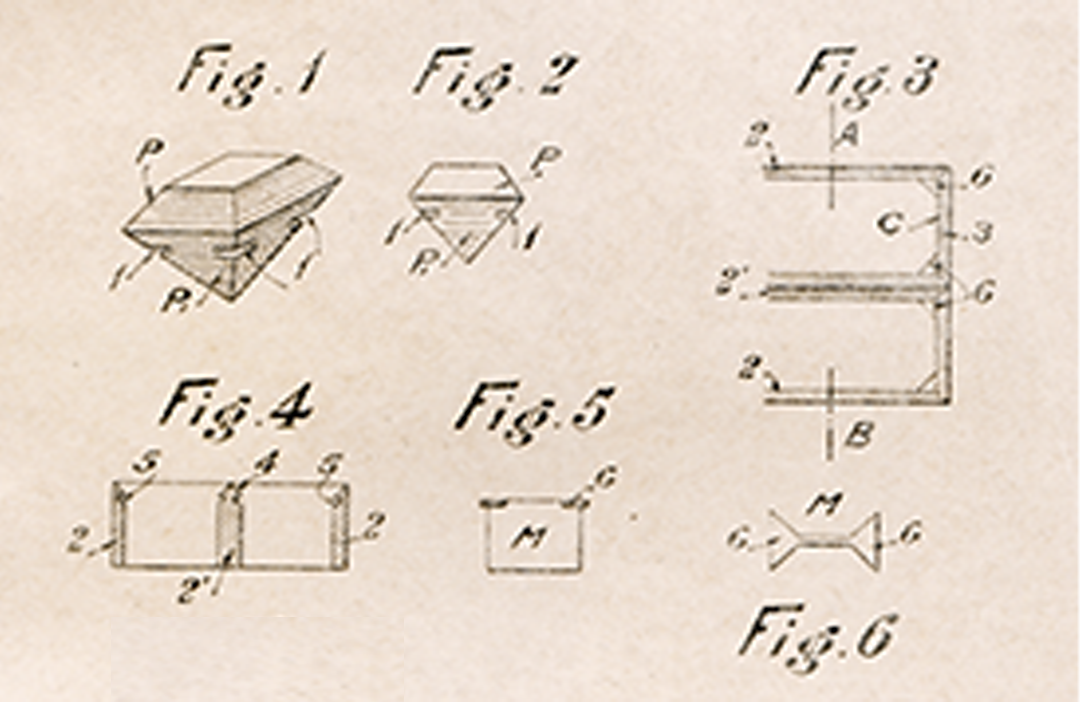

The Fleurs enlacées, roses rouges et blanches bracelet created in 1924 reinterpreted this popular motif. This piece won the Grand Prix at the Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes in 1925, illustrating the key role played by the Maison in celebrating Art Deco. In addition to its style, this piece also demonstrates a great mastery of modern techniques. Making things geometric and the quest for volume were represented by brilliant-cut diamonds16In 1919, the mathematician Marcel Tolkowsky published the ideal proportions of a diamond. This brilliant cut known as “modern” had fifty-seven facets, providing optimum radiance and brightness. and buff-top gems.17The buff-top is a recent cut, particularly used for colored stones in the Art Deco period. Buff-top gems have a cabochon-cut upper face and a faceted pavilion that provides a particular brilliance.

Fleurs enlacées, roses rouges et blanches bracelet

The story of the bracelet Fleurs enlacées, roses rouges et blanchesDiversification of material

Art Deco was also characterized by the use of little-known materials. Rock crystal, for instance, adorned long hat pins decorated with ears of wheat, providing both simplifica- tion and geometric sequencing. This enthusiasm for regularity of form and original materials is seen on certain powder compacts and cigarette cases. While their decoration is reminiscent of seventeenth-century Italian hardstone marquetry, their motifs, carved in blocks of ornamental or organic stone (such as malachite, onyx, mother-of-pearl, coral, and so on), are immensely regular. In addition to this mastery of glyptics on imposing minerals, the Maison excelled in working with miniature gems.

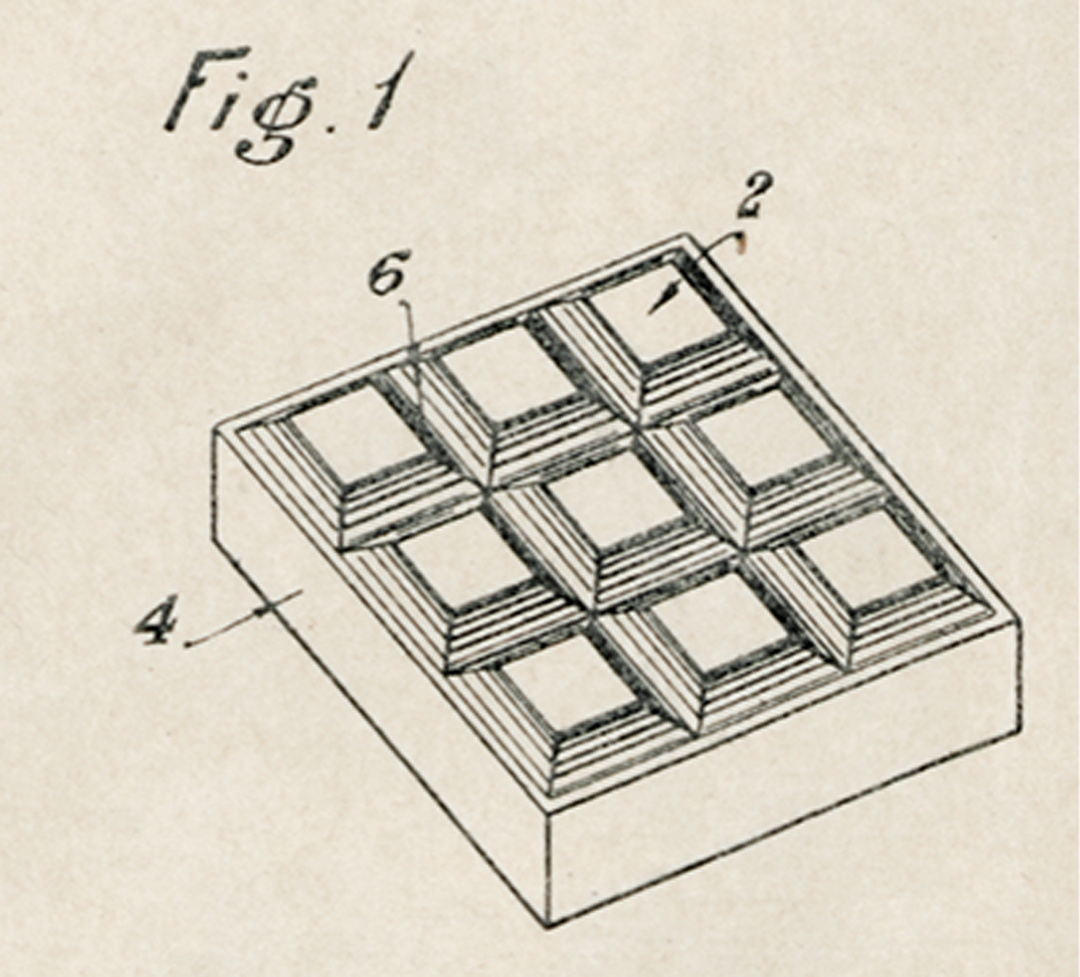

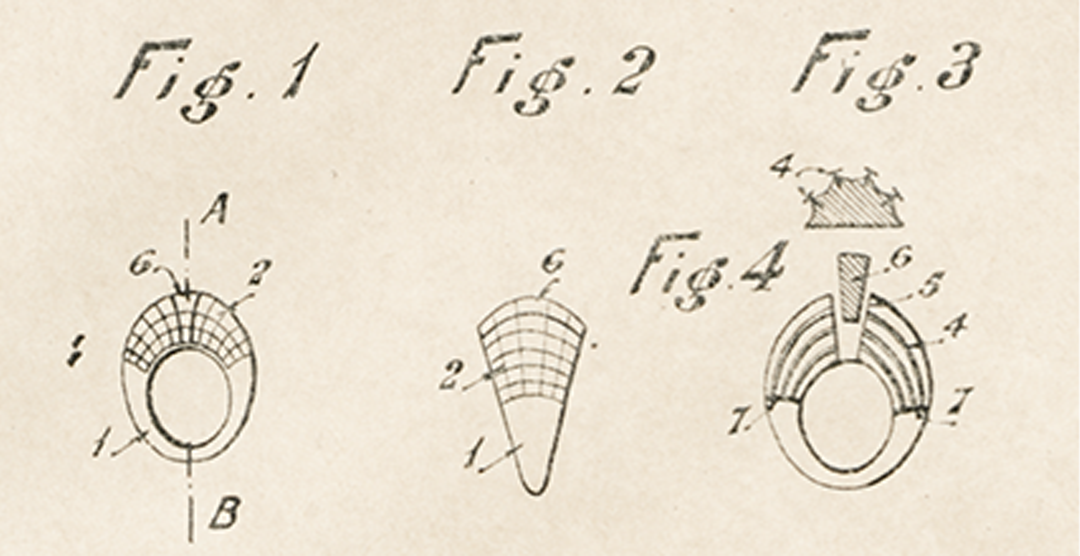

The mystery set technique

The mystery set—a technique patented in 1933 enabling the dimensions of gemstones to be adapted to the contours and volumes of pieces of jewelry—profoundly renewed the depiction of the plant world. The extremely careful pairing18The association of gemstones whose color, shape, purity, and dimensions are sufficiently close to appear identical. of the gems produced surfaces of homogenous tones and heightened the velvety aspect of the petals and leaves. The rubies and sapphires, favored for their hardness and color density, were calibrated and slid into yellow gold rails, effectively creating gemstone marquetry without a visible mount.

This innovation, which was initially tried out on flat surfaces such as box lids, revolutionized the look of floral clips after 1936, as seen in one of the earliest examples of this form, the Flower brooch. The Peony and Chrysanthemum clips both feature in Van Cleef & Arpels’ display at the 1937 Exposition internationale des arts et des techniques appliqués à la vie moderne in Paris. Today, these two pieces, together with the Flower brooch, still attest to the Maison’s ability to apply modern techniques to the style of the moment, confirming its originality.

Chrysanthemum clip

On the so-called “hummingbird” box dating from 1938, the mystery set enables a play of relief on the piece’s surface. The flat tints and volumes, the asymmetry of the composition, and the uneven outline of the branch recall certain conventions of Asian pictorial art.

Renewal of figurative inspiration

Shortly after the 1937 Exhibition, the geometric and abstract forms of Art Deco gave way to figurative inspiration once again. This was, however, different to the creations dating from the start of the twentieth century; floral and animal motifs were looked at again, notably as a result of the economic and political contexts, but also due to esthetic factors. The restrictions caused by the Second World War (i.e., the requisition of platinum for weaponry, and the lack of precious metals and gemstones) triggered a stylistic revival. Yellow gold, historically a safe bet in times of instability, once again became the metal of choice.

Customers did not hesitate to have their old jewelry melted down to create new pieces, thereby conserving their heritage. A number of works from the 1940s were therefore characterized by large yellow gold mounts set with just a few stones—a novel style in keeping with the Modernist current in vogue at that time.19The Modernism of the 1940s was characterized by sober, pared-down, symmetrical geometric forms devoid of ornamentation and applied to rounded surfaces. The influence of the Surrealists nonetheless added a touch of the Baroque to this apparent sobriety, which explains the references to the Rococo and Napoleon III styles. In jewelry, this is referred to as “retro style.” Despite their imposing appearance, these pieces were immensely delicate. As gold became scarcer, it was engraved, worked into volutes, curves, and fine resilla, polished and even braided, enabling the Maison to create jewelry of unprecedented delicacy.

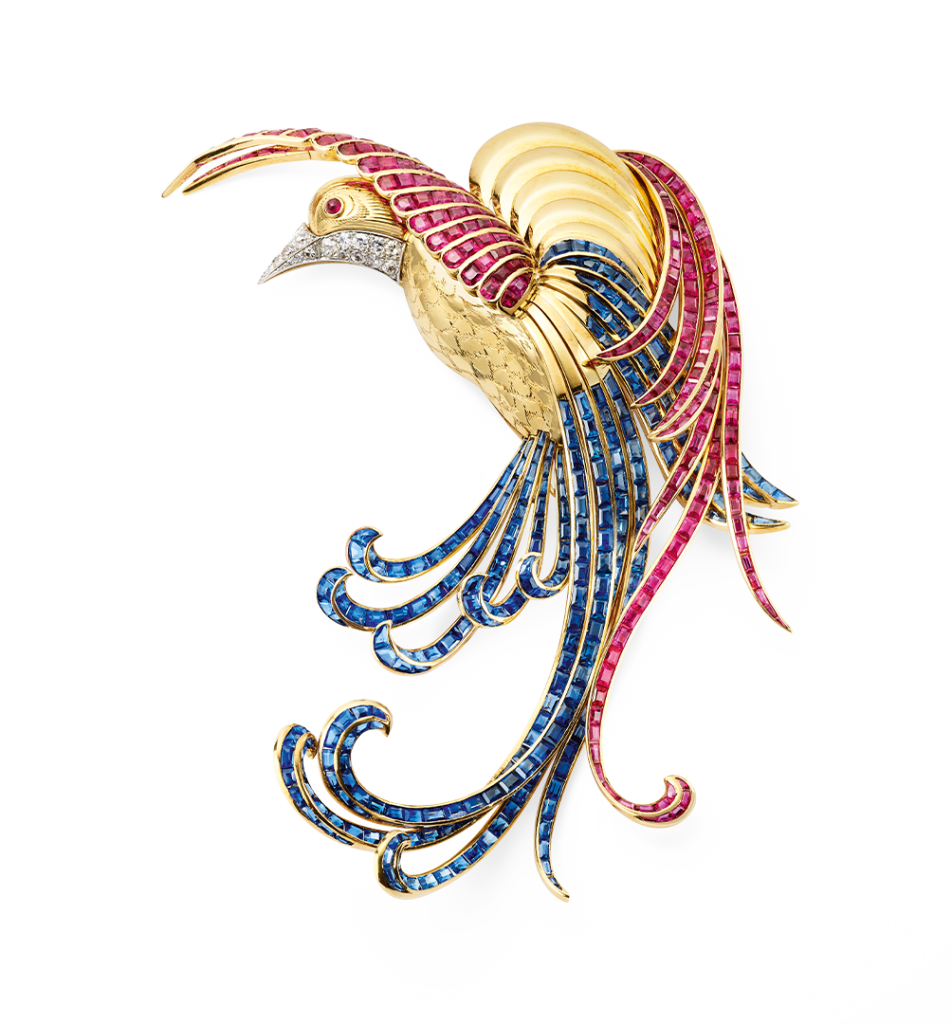

The slender silhouette and stylized feathers of calibrated rubies and sapphires in the Bird clip of 1942, magnified by the polished, engraved gold, provided spectacular contrasts. The name of this piece calls to mind a bird—a symbol of freedom and hope during the Second World War20For more on the symbolism of the bird in jewelry, see Guillaume Glorieux, ed., Paradis d’oiseaux [exhib. cat.] (Paris: École des Arts Joailliers, 2019.).—but also a flower of the same name. Like the bird, this flower evokes joy through its spectacular shape and lively colors.

Reference to the floral language of the early nineteenth century remained constant: apart from animals which were symbols of hope, bouquets in carefully chosen patriotic colors (the red, white, and blue of the Allies) formed sprays of flowers, as seen in the Passe-Partout jewelry range and the Hawaii collection. Immediately after the war, buttercups were to be found on jewelry as an ode to joyfulness and renewal, arranged around the wrist with a watch dial in the middle or as a motif in a bouquet, their solar corollas lit up by ruby and gold pistils.

Influence of Haute Couture

From the 1930s, Van Cleef & Arpels’ inspirational sources were many and varied. Couture gradually became one of the subjects most frequently associated with nature. This hybridization21See the report of a symposium held at the Maison de la Recherche in Paris on January 21, 2013. https://www.ciera. hypotheses.org/578 may, in part, be explained by the revival of Parisian haute couture. The early designs of Maison Christian Dior, founded in 1947, shook up the fashion world. Their new lines, inspired by the fashion of the Second Empire, formed a clean break with those of the “woman-soldier” and gave rise to the expression “woman-flower.”22Christian Dior, ‘Palmyre’ evening dress, embroidered with garlands and flowers of Indian and eighteenth- century Rococo style inspiration, Spring- Summer 1952. Paris, Palais Galliera-Musée de la Mode, no. inv. 22-534071. The “New Look”—so named by the editor-in-chief of Harper’s Bazaar—emphasized slender waists and more pronounced hips, giving the illusion of a flower’s corolla. Flexible lines and ample fabric were also favored by Pierre Balmain, who later created the “pretty Madame” style.

In keeping with this fashion, the purses and Minaudières made in the 1940s were covered in daisies, a flower that was particularly popular with designers.23Marie-Louise Carven, Marguerite, summer 1952, drawing. Paris, Palais Galliera- Musée de la Mode, no. inv. 2015.0.29.179. This cross-pollination between the plant world and that of high fashion gave rise to bold, lively compositions. This is seen in the Little Flowers bracelet of 1946, where the gold “tulle” of the petals looks like fabric. This extremely fine, undulating resilla is edged with slightly thicker polished gold thread, highlighting the movement of each petal.

Avant-garde reinterpretations of nature

Taken to extremes, this hybridization assumed unexpected forms. Eager to be in step with the zeitgeist, Van Cleef & Arpels reinterpreted nature by combining it, in the 1930s, with the new approaches of contemporary art. Alexander Calder’s jewelry24On this subject, see: Karine Lacquemant, Bijoux d’artistes, de Calder à Koons: la collection idéale de Diane Venet [exhib. cat.] (Paris: Flammarion / Musée des Arts Décoratifs, 2018). and sculptures on metallic stalks, for instance, were probably the inspiration for the avant-garde pieces called Fleur Silhouette. The long and thick gold thread (roughly 3’11”) with which they were made was coiled around a center set with diamonds, rubies, or sapphires, conjuring up flowers and bows.

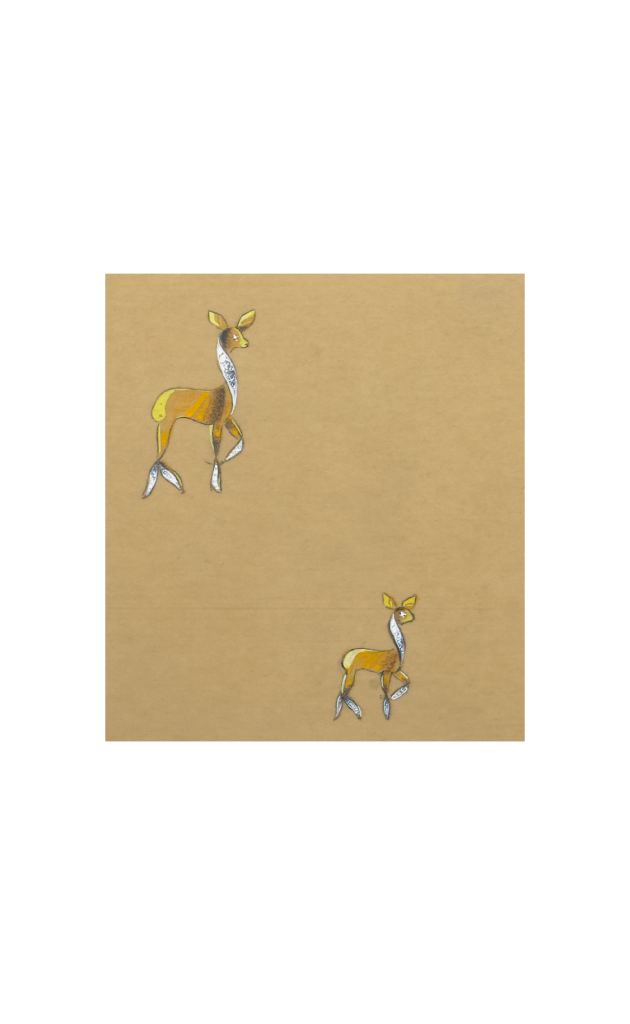

Ribbons were also right back in vogue, in a revived and particularly modern fashion, applied to animal clips. These clips borrowed their flexible forms from the textile repertory, fluctuating between natural and fanciful effects. In 1946, the body of a Deer clip was created with a ribbon of twisted yellow gold, and the previous year, a Cockerel clip was given a most unusual form: while the animal was recognizable, the yellow gold strips with which it was made also evoked a musical instrument.

DRAWINGS OF ANIMAL CLIPS

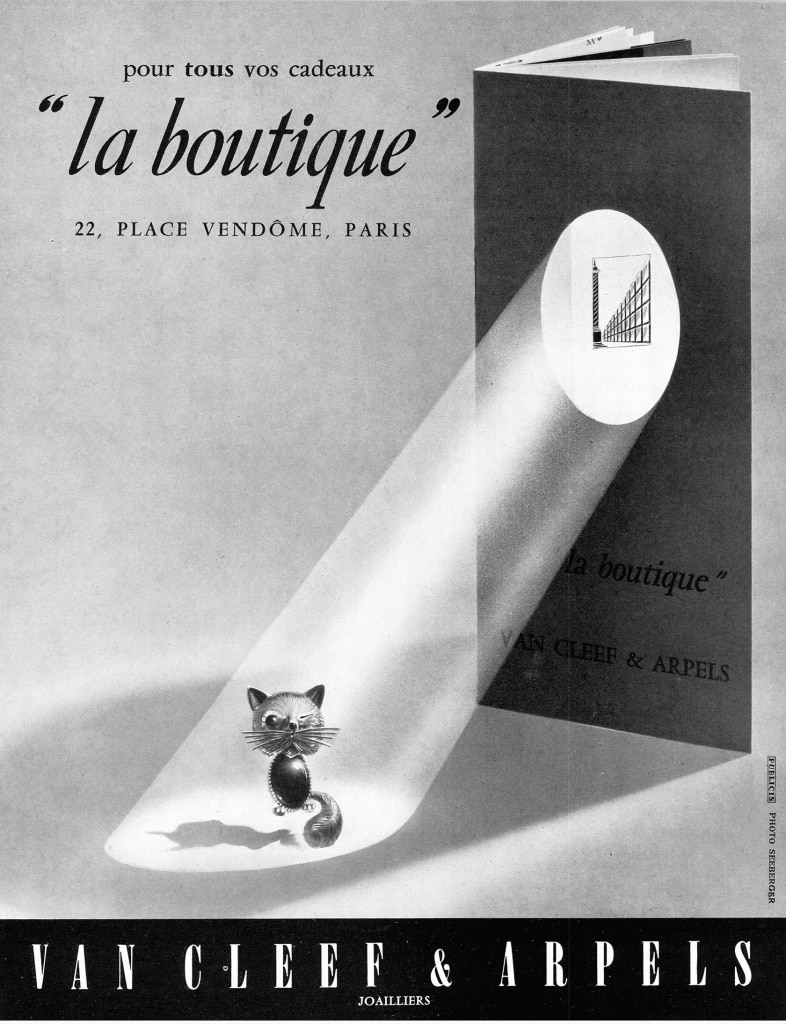

Creations of “La Boutique”

These particularly modern, pared-down pieces of jewelry were short-lived yet remark- able forms of expression that heralded the creations that followed in the early 1950s. The major changes that took place in society during the post-war boom decades in France disrupted the way in which jewelry and accessories were worn. While daytime was given over to bright jewelry in yellow gold, with ranges of motifs gathered to form stylized floral ensembles, like the Chantilly motif,25The Chantilly motif is a small mirror-polished yellow gold petal that folds in two. The name recalls the French town famous for its lacework, while its form resembles a grain of wheat. Used together with spiral motifs, the ensemble appears to form delicate flowers that are almost abstract. evening was the time for displaying jewelry largely composed of white metals and diamonds, the brilliance of which was enhanced by artificial lighting.

DRAWINGS OF CHANTILLY JEWELRY

The jewelry designed for La Boutique, from 1954, revolutionized traditional codes. It was made in small series and sold at affordable prices in order to attract a younger clientele. These pieces included animal clips almost certainly inspired by American cartoons in vogue at that time. Their silhouettes were skillfully rendered, but their proportions were altered, playing with the characteristics of each species to give them a mischievous look. A baby bird in a clip of the same name appears to have fallen out of its nest, while a cat in another clip winks playfully. Meanwhile, the heads of the Squirrel and Mouse clips form hearts as their snouts seem to quiver with joy. Nature assumed another dimension within the Maison’s production with the creation of the “La Boutique” concept.

Building an identity

From good-luck medals with clovers and black cats to sumptuous floral jewelry sets in the 1950s, via landscapes adorning accessories in the 1920s and 1930s, nature, an unfailing source of inspiration, enabled other subjects to be introduced that subsequently became signatures of the Maison: luck with its symbols of good fortune, and love through its floral and animal language.

These works revealed Van Cleef & Arpels’ constant quest to reproduce and reinterpret nature as something alive and beautiful in the sense given to it by the writer Roger Caillois in 1962: “Natural appearances are the only conceivable origin of beauty. Everything that is natural or that resembles nature; that reproduces or adapts its forms, proportions, symmetry, and rhythms is deemed to be beautiful and felt to be as such.”26Roger Caillois, L’Esthétique généralisée (Paris: Gallimard, 1962): 20. Nature, whether animal or vegetable, provides an important source of inspiration for the Maison, contributing to its specific identity. These numerous reinterpretations highlight its ability to be part of a constantly evolving art scene. Nature in Van Cleef & Arpels’ production is distinguished by its immense variety, and by its constant search for and expression of beauty, which is translated into jewelry motifs with the eye of a botanist or zoologist, and reinterpreted with inventiveness when the context requires, or influenced by stylistic trends.