Marion Mouchard

Art Deco,1The term “Art Deco” was posthumously attributed by Bevis Hillier in his book Art Deco of the 20s and 30s (1968) in reference to the 1925 Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes. The expression “the 1925 style” also refers to the art of the 1920s. an art movement that emerged in reaction to Art Nouveau, influenced all the visual and applied arts from the early twentieth century through to the Second World War. It assumed many different forms throughout this period, contributing to the heterogeneity of the movement, otherwise known as the “1925 style”…

In the early years of the twentieth century, an esthetic of “intentional simplicity and evident symmetry”2Art Nouveau was an international art movement that owed its French name to Siegfried Bing’s Paris gallery, La Maison de l’Art Nouveau, founded in 1895. The style was characterized by the predominance of plant iconography that inspired organic lines and the so- called “whiplash” motif of exaggeratedly elongated curves. emerged in opposition to the complex tangle of “whiplash” lines of the 1900 style.3André Véra, “Le Nouveau style,” L’Art décoratif (January 1912): 30. “Beauty of materials,” “perfect proportions,” and “clear opposition of colors”4André Véra, “Le Nouveau style,” L’Art décoratif (January 1912): 30. were once again deemed important. The social and technological developments of the interwar period, namely the democratization of sport, the more generalized use of transport, and the relative emancipation of women, conditioned the evolution of the female silhouette and, by extension, women’s finery. The first signs of this new movement within the jewelry arts were seen in the early twentieth century,5We refer here to the creations of the Mellerio and Cartier jewelry Maisons, notably those by the designer Charles Jacqueau, who worked for Cartier. See Heather Ecker, Judith Henon-Raynaud, Sarah Schleuning, Cartier and Islamic Art [exhib.cat.] (London: Thames & Hudson, 2021). and its progress accompanied the rise of Van Cleef & Arpels, as seen in one of the early jewelry sets created by the recently founded Maison.

The beginnings of Art Deco in Van Cleef & Arpels creations

This early example of Van Cleef & Arpels’ adherence to the Art Deco esthetic coincided with the advent of Émile Puissant who, from 1918, provided the Maison with new stylistic and commercial momentum. The creative wealth of the Van Cleef & Arpels’ production between 1919 and the early 1930s was concurrent with the developments and diversity of the Art Deco movement.

The legacy of the eighteenth century

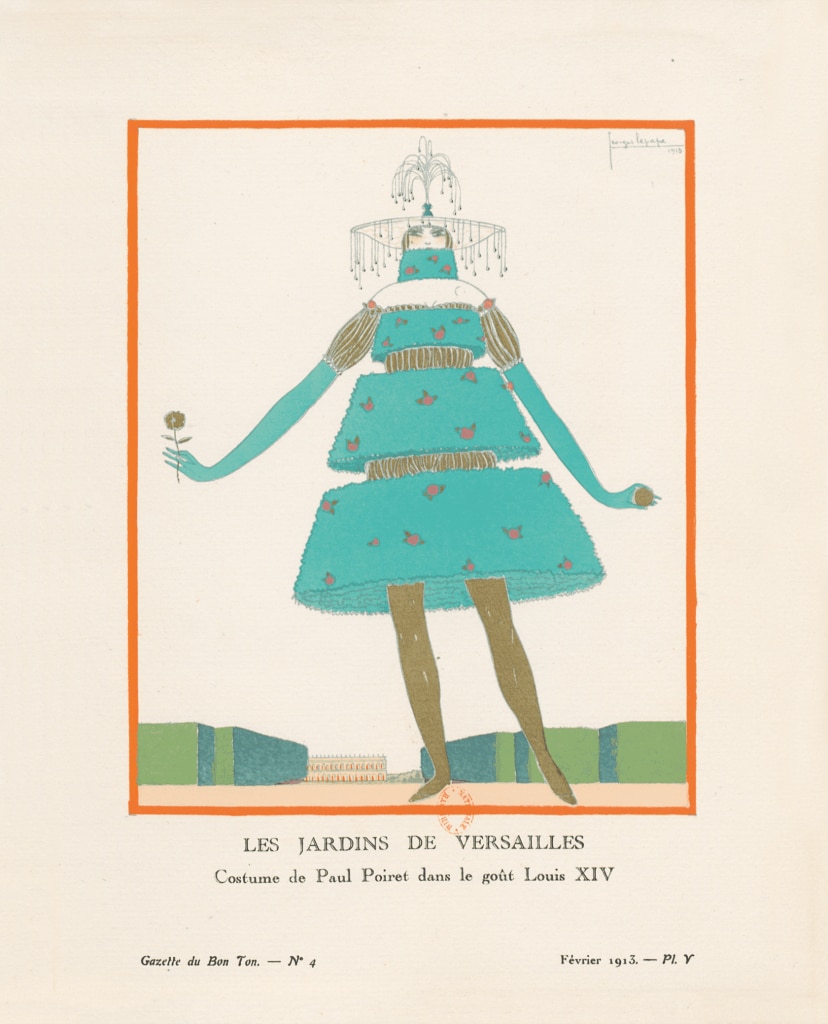

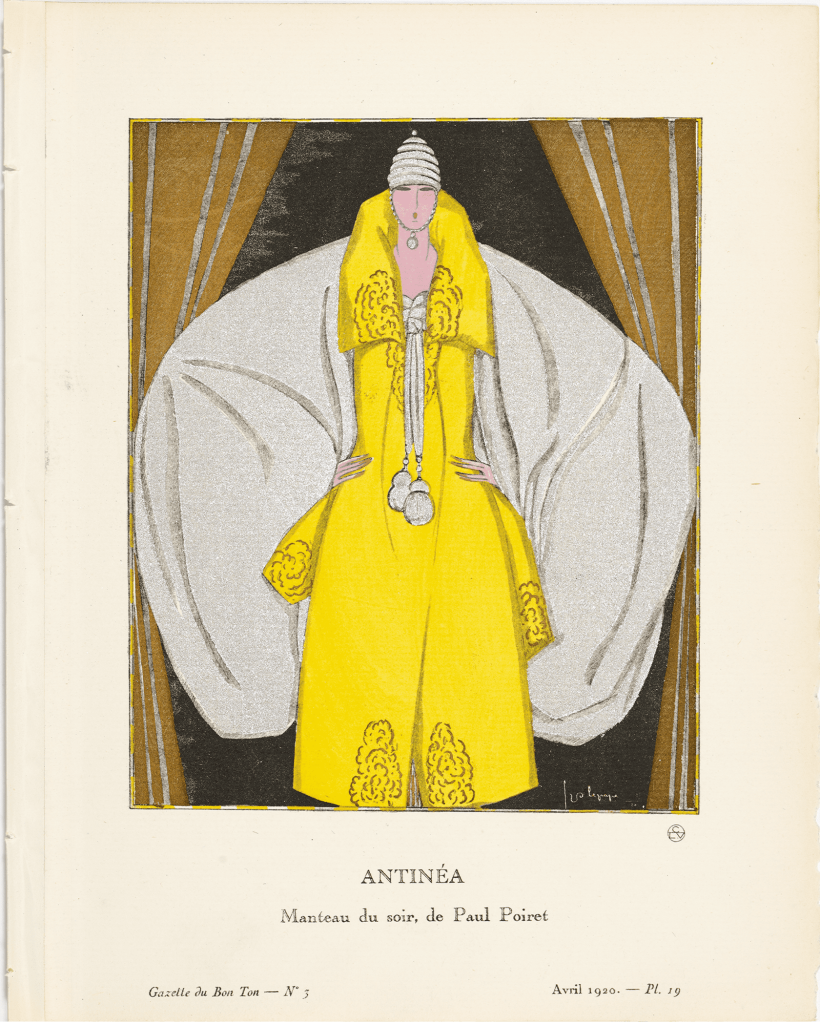

The earliest expressions of Art Deco in the 1910s illustrate a decidedly traditionalist esthetic, with designers looking to the stylistic repertoire of the Ancien Régime, notably the Louis XVI style, in order to revive the French decorative arts. They borrowed naturalist motifs from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, “gathered in […] baskets or plaited in […] garlands,”6André Véra, “Le Nouveau style,” L’Art décoratif (January 1912): 32. in a loosely assertive style. Such reminiscences, seen in the work of couturiers like Paul Poiret and decorators like André Groult, were echoed in the work of Van Cleef & Arpels at the start of the 1920s.

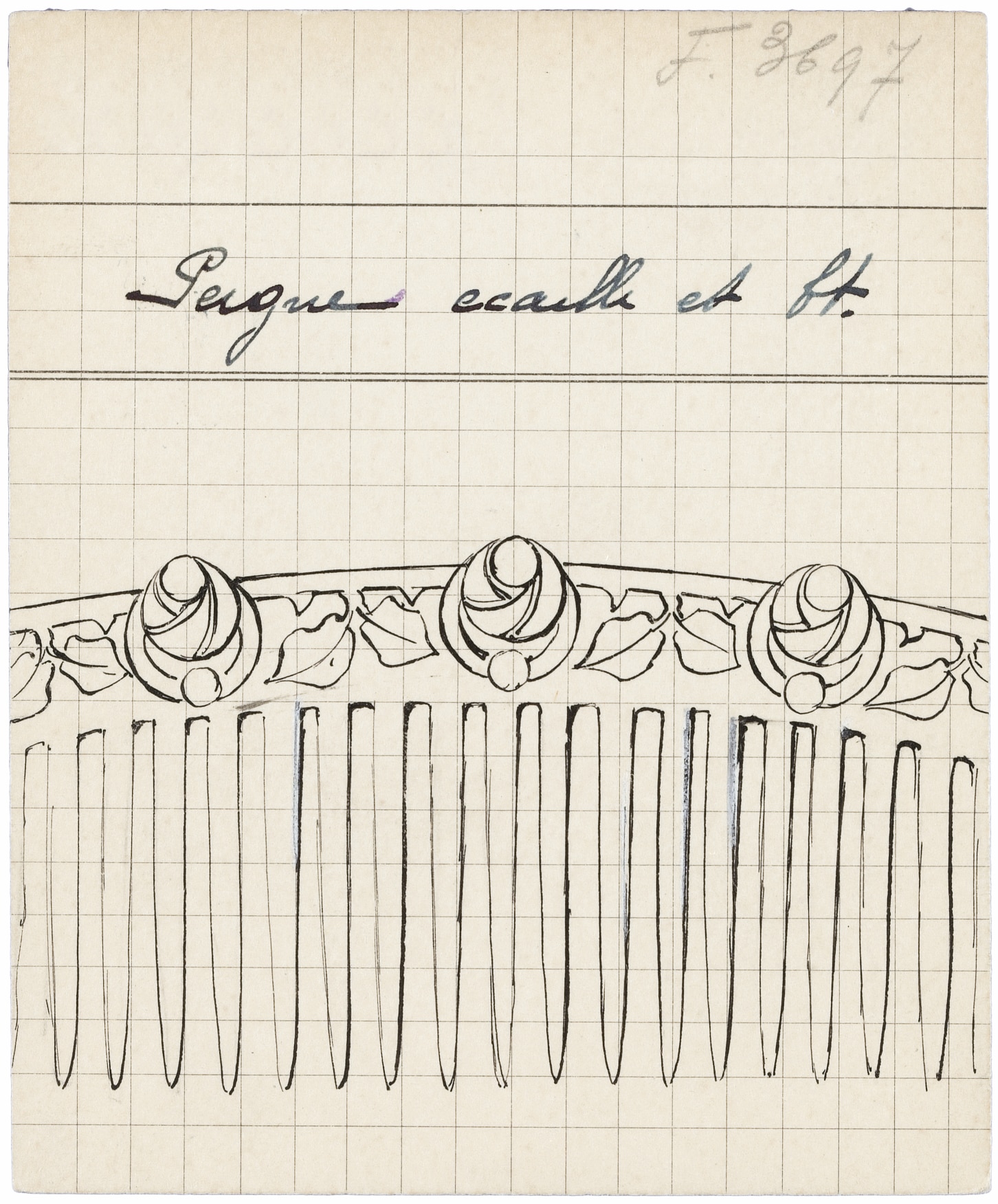

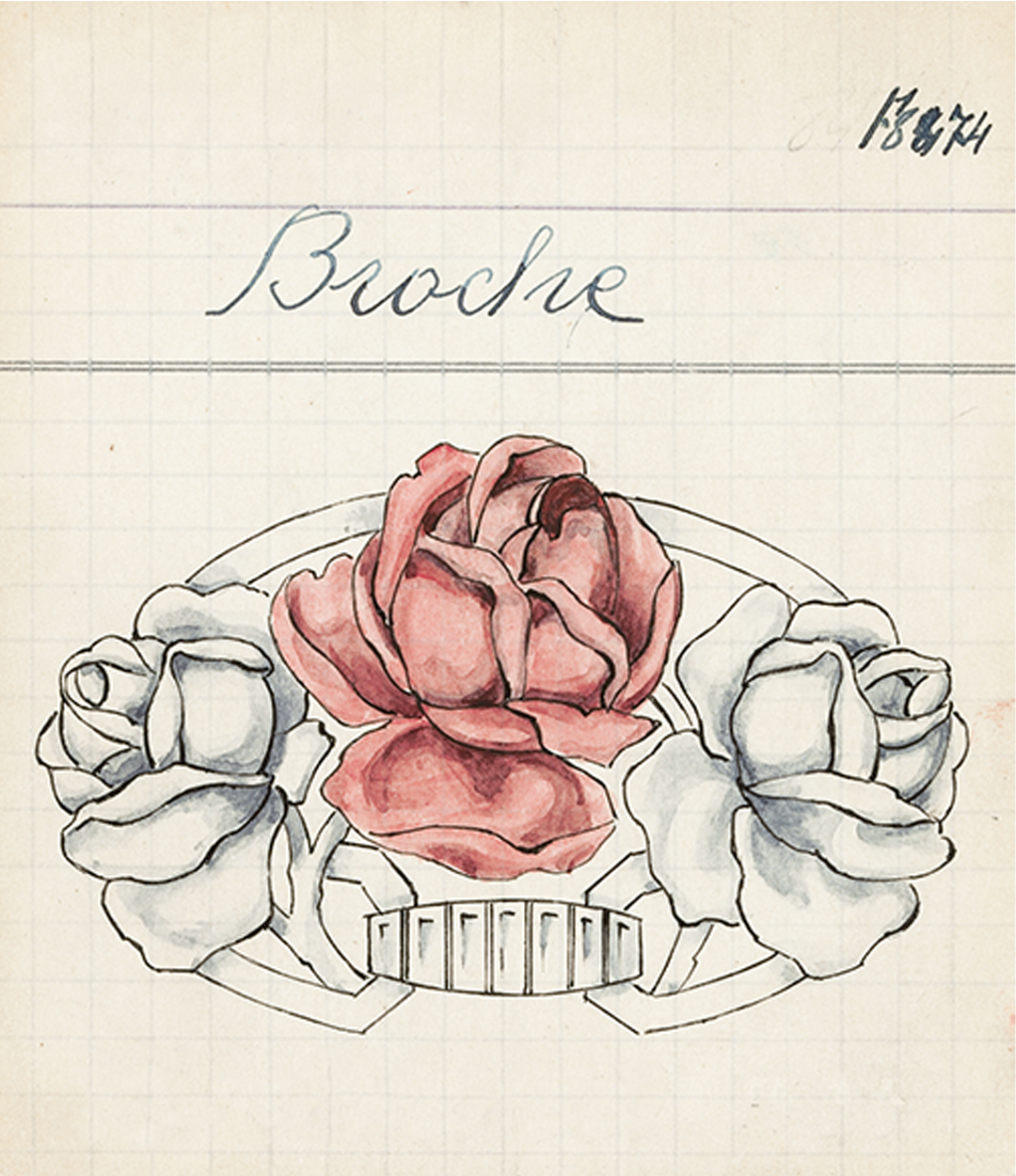

In 1922, for example, a rose pattern in brilliant-cut diamonds was repeated like a frieze on a hair comb. This floral design, with its simplified contours evoking one created by Paul Iribe as early as 1908, was also used on band bracelets. Such a type of band was perfectly suited to highly symmetrical, recurring patterns. These bracelets, made of platinum and brilliant-cut diamonds, illustrate the use of such traditional iconography for particularly luxurious creations typical of the early Art Deco period. The geometric decomposition of the flower coexisted with a greater fidelity toward floral representation.

This is true of a brooch inscribing three flower heads set with diamonds and rubies in an oval frame, but also and above all in a group of pieces presented by Van Cleef & Arpels at the 1925 Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes in Paris. At this event, which was attended by no less than four thousand visitors on the opening day at the Grand Palais on 28 April 1925, with twenty-one participating nations, the Maison was awarded a Grand Prix for a bracelet and brooch with entwined roses, one in buff-top rubies and the other in brilliant-cut diamonds.

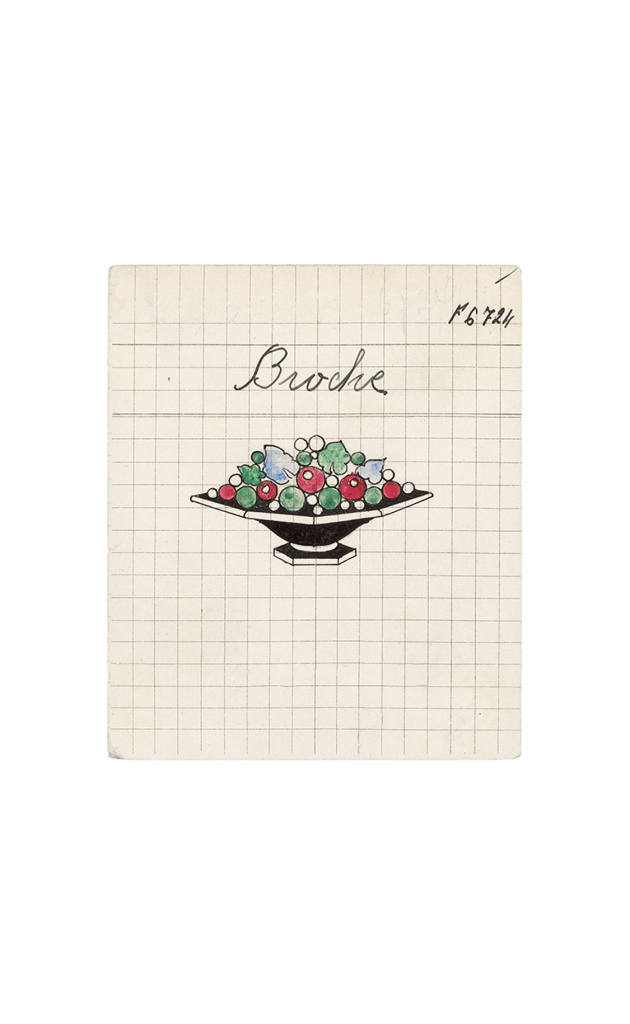

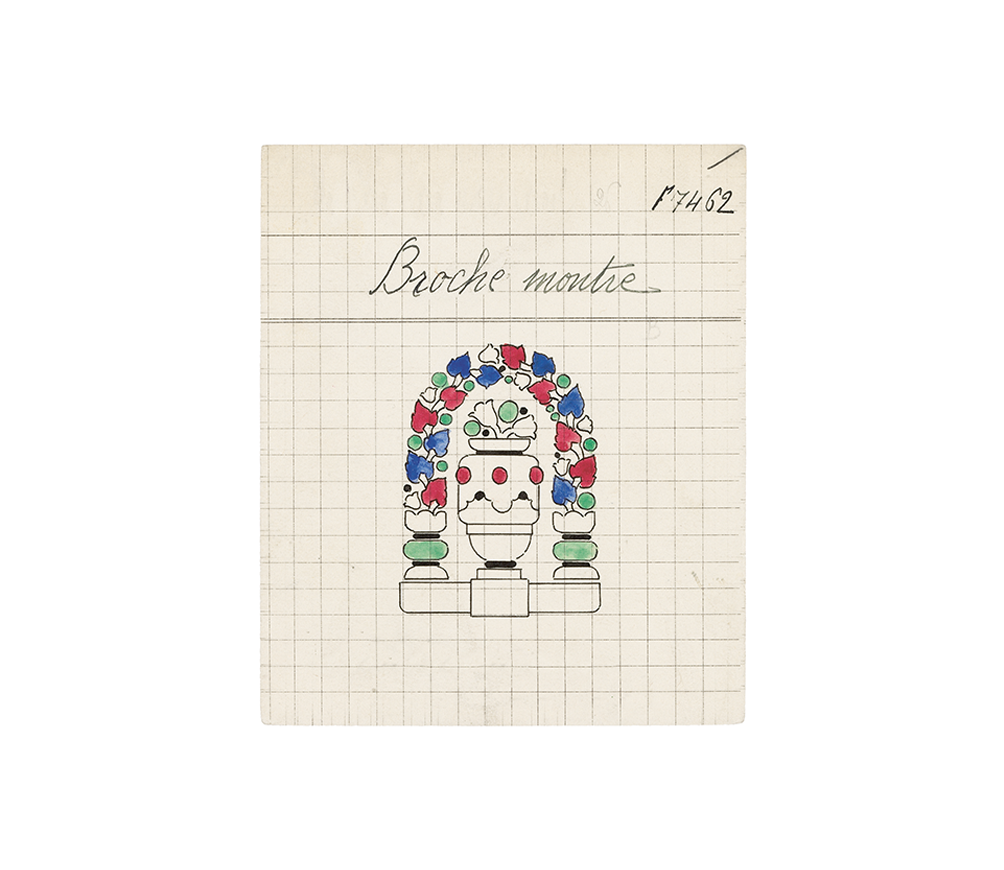

While the rose was one of the Maison’s favorite ornaments during the 1920s, baskets of flowers featured in many different types of jewelry during the same period: châtelaine watches, brooches, brooch watches, and pendants. Some of these pieces were interpreted in white diamond jewelry, but the majority were colorful creations with rubies, sapphires, and engraved emeralds. Emeralds, traditionally found in Indian jewelry, were used here to create leaves and flowers. They were also found on a Cornucopia brooch, the subject of which is also derived from ornamental vocabulary from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

BASKET OF FLOWERS ORNAMENTS

A strong interest in non-European arts

Reference to “the French tradition”7André Véra, “Le Nouveau style,” L’Art décoratif (January 1912): 31. nonetheless cohabited with an interest in non-European art that was boosted by international exchange. Alongside the development of Art Deco in the early years of the twentieth century, the Ballets Russes was giving its first performances in Paris. Its rich iconographic repertoire ranged from Ptolemaic Egypt (Cleopatra) to the Persian dreamworld of the tales of the One Thousand and One Nights (Sheherazade), via the “India of fables”8Jean Cocteau, Frédéric de Madrazo, Programme officiel des Ballets russes (Paris: M. de Brunoff, 1912). in Le Dieu bleu.

These theatrical visions contributed to an intense fascination for distant lands, which was also found in the applied arts. This could be seen in the apartments of the couturier Jacques Doucet, where an occasional table by Paul-Louis Mergier reinterpreted Chinese cabinets alongside an Egyptian-style trinket tray and African chairs by Pierre Legrain.

Fashion designers also adopted the prevailing geographic and cultural eclecticism for their garments.

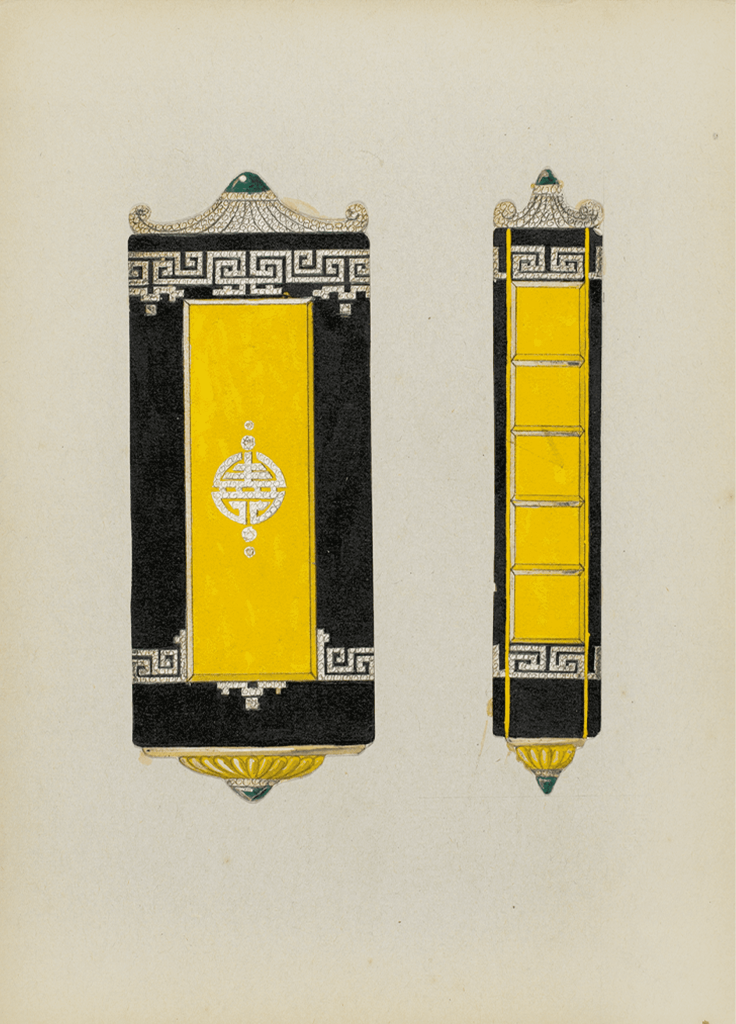

Similarly, “jewelry designers […] look[ed] […] to the Orient”9[Ministère du Commerce, de l’industrie, des postes et des télégraphes], Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes, Paris 1925: rapport général. Section artistique et technique (General Report: Artistic and Technical Section), Vol. IX, Parure (Finery) (Classes 20 to 24) (Paris: Librairie Larousse, 1927), 86.—one that was vast and vague and included Egypt as well as India, China, and Japan. It features in the work of Van Cleef & Arpels from the very end of the 1910s, in early pin brooches with lotiform and papyriform heads. From then on, the Maison aimed to combine Eastern-inspired forms, materials, and iconographies with traditional Western jewelry. Inrōs,10Small boxes, originally from Japan, worn by men who attached them to the belt of their kimonos with a cord. in particular, inspired new forms of women’s nécessaires in the early 1920s. In the previous decade, these containers had been rectangular in shape or appeared as small clutches, but they were now cylindrical and linked to a ring by a chain, like traditional Japanese inrōs.

DRAWINGS OF NÉCESSAIRES

The first of these creations adopted the neoclassical motifs of white diamond jewelry with bichrome decoration (black enamel and diamonds) typical of the 1910s. Gradually, these nécessaires came to be inlaid with figurative decoration in lacquer or carved ornamental stones. The interest in Asian and African art encouraged a rich diversity of materials that characterized the decorative arts in the 1920s, especially the jewelry arts. The designers and craftspeople working for Van Cleef & Arpels studied “the way in which Asia uses jades, corals, enamels, and pearls to obtain particular color effects.”11[Ministère du Commerce, de l’industrie, des postes et des télégraphes], Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes, Paris 1925: rapport général. Section artistique et technique (General Report: Artistic and Technical Section), Vol. IX, Parure (Finery) (Classes 20 to 24) (Paris: Librairie Larousse, 1927), 86. When the constraints of the scale of jewelry prevented the use of these materials, they were imitated with the use of colored enamels.

The arts of these distant lands also provided a vast figurative repertory. “The magnificent ornaments […] [of] archaic Chinese bronzes” were adapted to cigarette cases and nécessaires “to powerfully simple effect.” The abundance of iconographic sources inspired a multitude of jewelry types—sautoirs, brooches, châtelaine watches, and bracelets—all of which displayed the same craftsmanship. They “reproduced in color stones [buff-top rubies, emeralds, and sapphires] on a background of brilliant-cut diamonds, characters […] [and] motifs […] borrowed from […] Egyptian [bas-reliefs]”12[Ministère du Commerce, de l’industrie, des postes et des télégraphes], Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes, Paris 1925: rapport général. Section artistique et technique (General Report: Artistic and Technical Section), Vol. IX, Parure (Finery) (Classes 20 to 24) (Paris: Librairie Larousse, 1927), 86., Indian gold and silverwork, and Japanese prints.

The “cubist style”

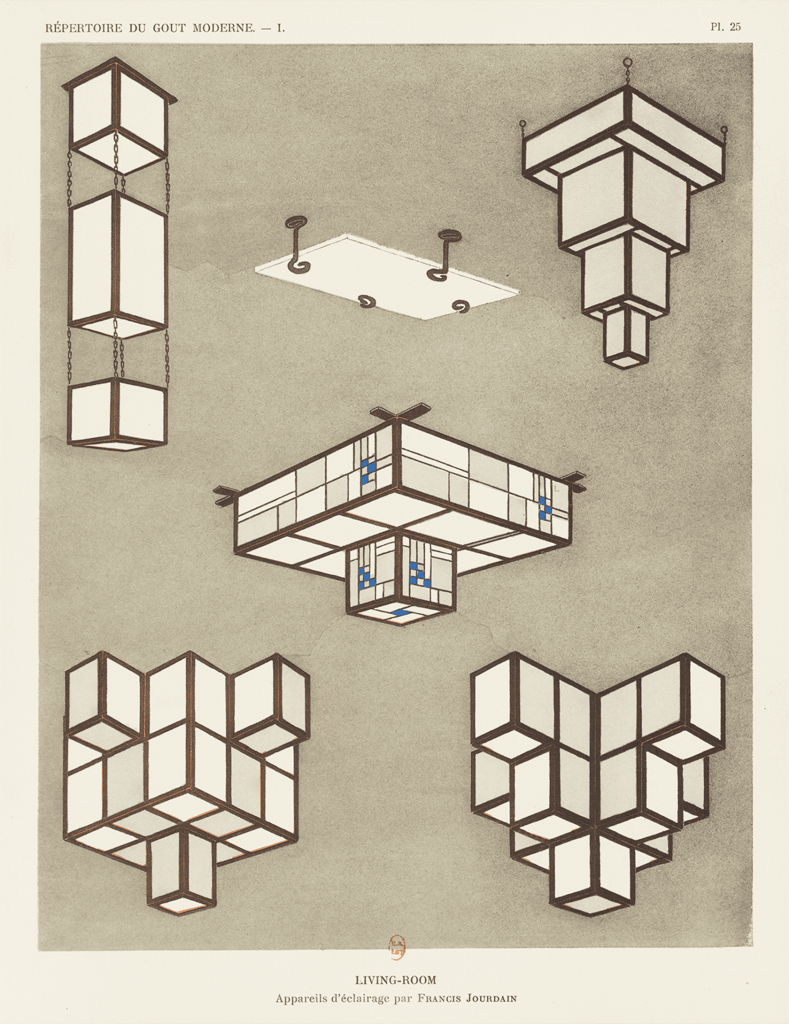

In parallel with this figurative iconography, a purely abstract, decorative vocabulary evolved, composed of simple geometric forms inspired by Cubism.13[Ministère du Commerce, de l’industrie, des postes et des télégraphes], Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes, Paris 1925: rapport général. Section artistique et technique (General Report: Artistic and Technical Section), Vol. IX, Parure (Finery) (Classes 20 to 24) (Paris: Librairie Larousse, 1927), 86. The links between this second aesthetic of Art Deco and the avant-garde movements of the early part of the century were already seen in the 1910s, and were formalized in a joint venture, the Maison cubiste, that illustrated the rapport between representatives of different artistic practices. The project was jointly conceived by the sculptor Raymond Duchamp-Villon, the interior decorator André Mare, and the painters Fernand Léger, Albert Gleize, and Jean Metzinger. It provided a cubist vision of architecture and design that was presented in the “decorative art” section of the Salon d’Automne in 1912.

That same year, Gleize and Metzinger published their manifesto, which created a theoretical premise for Cubism.14Albert Gleize, Jean Metzinger, Du cubisme (Paris: Eugène Figuière, 1912). See also: Cubism (London: T.F.Unwin, 1913). Henceforth, even if the interior of the Maison cubiste dreamed up by André Mare still bore the mark of a tradition centered around furniture and furnishings, the angular, geometric compositions of Cubism were reflected in the stylization and ornamental austerity of the decorative arts of the 1920s.

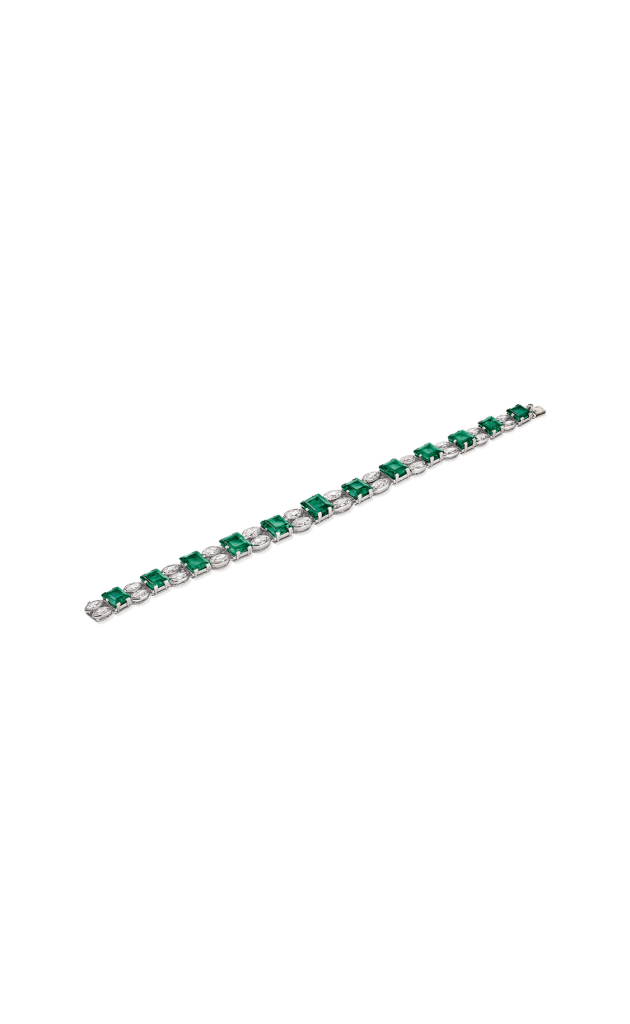

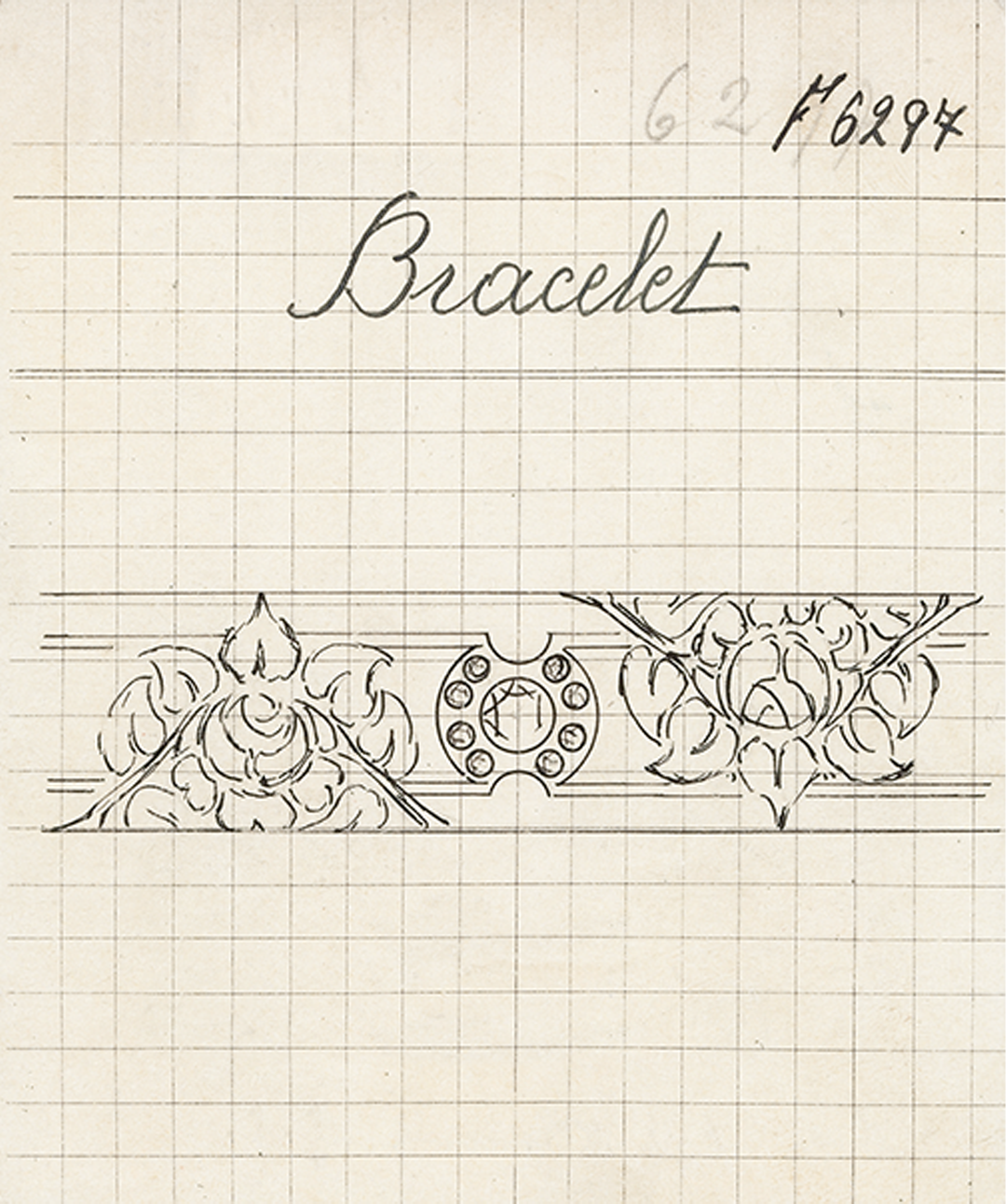

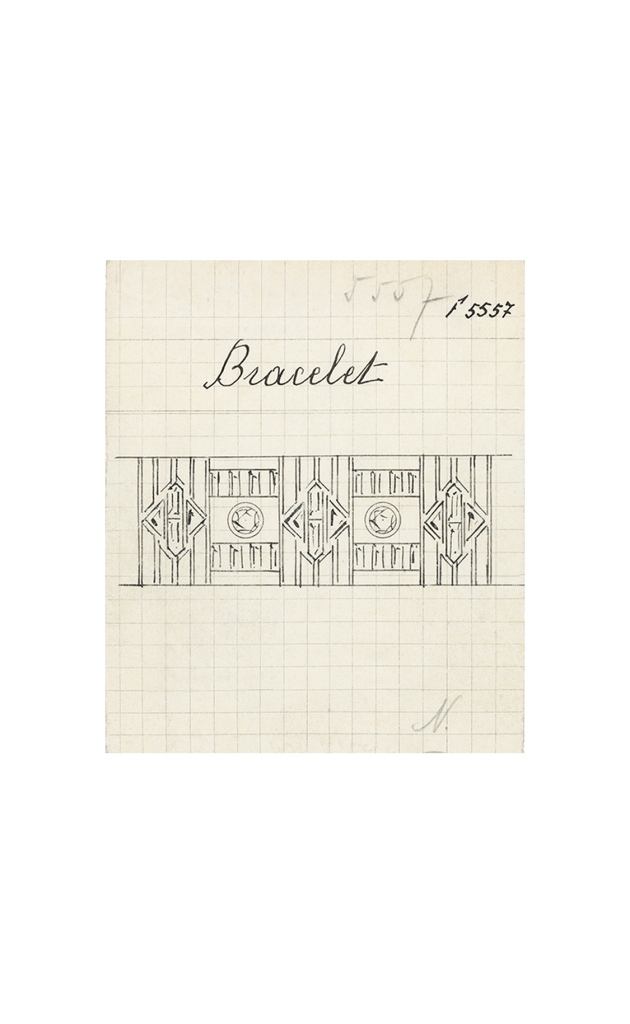

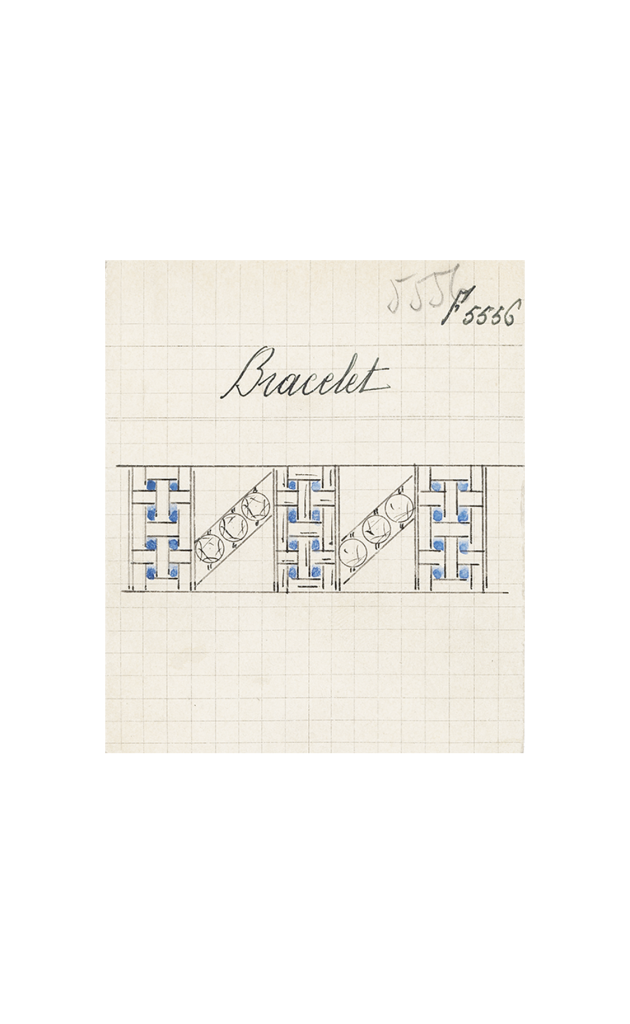

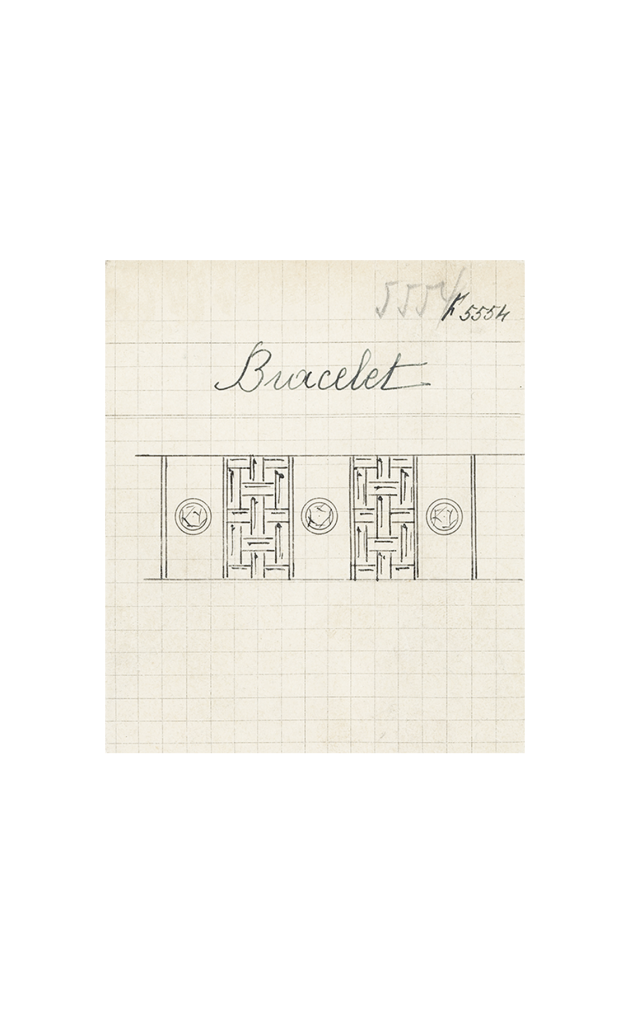

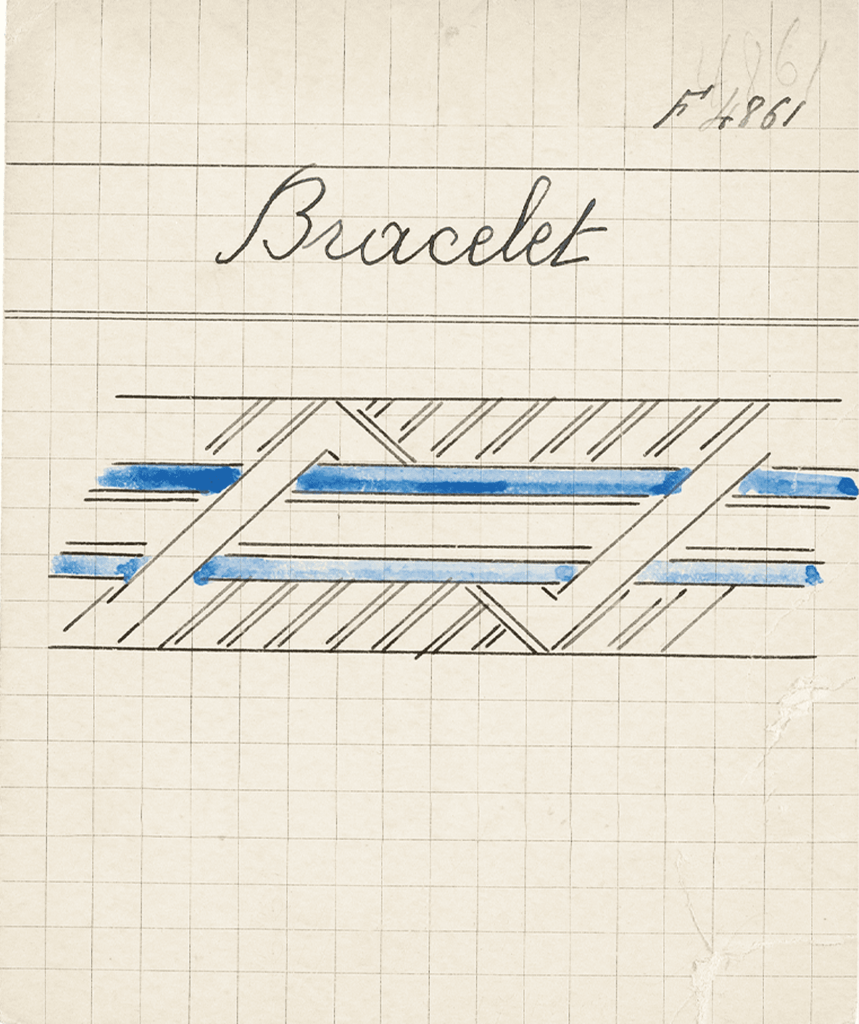

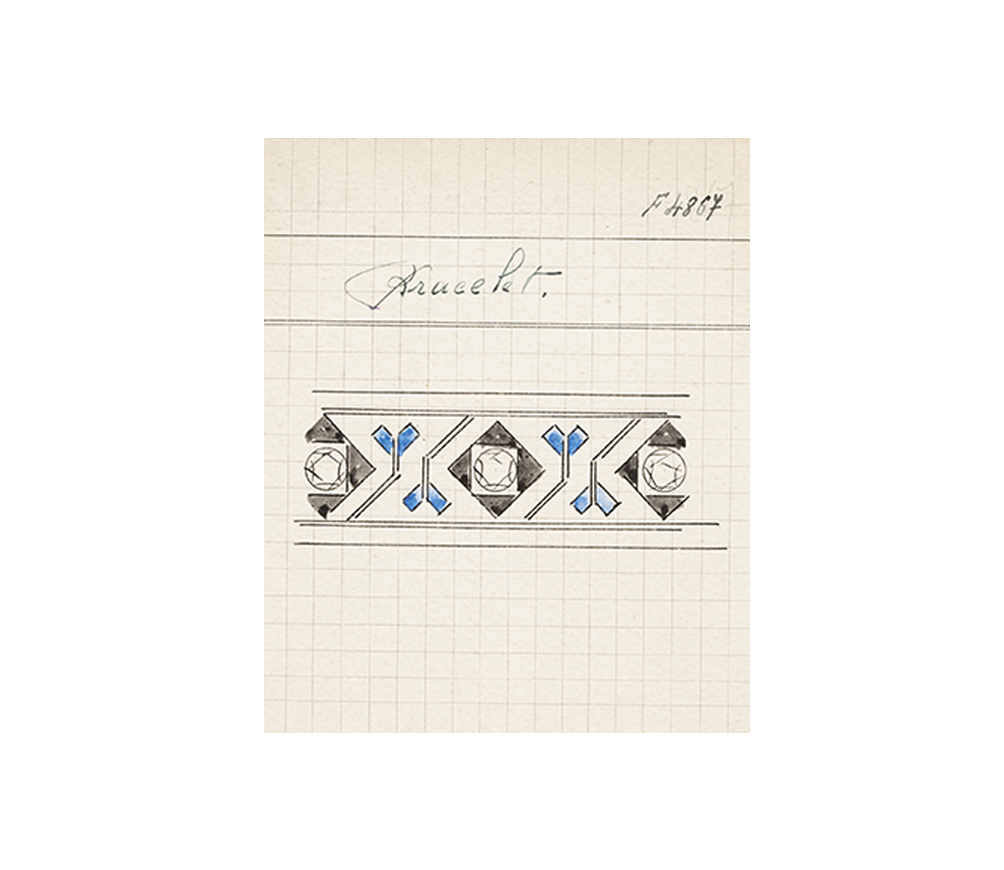

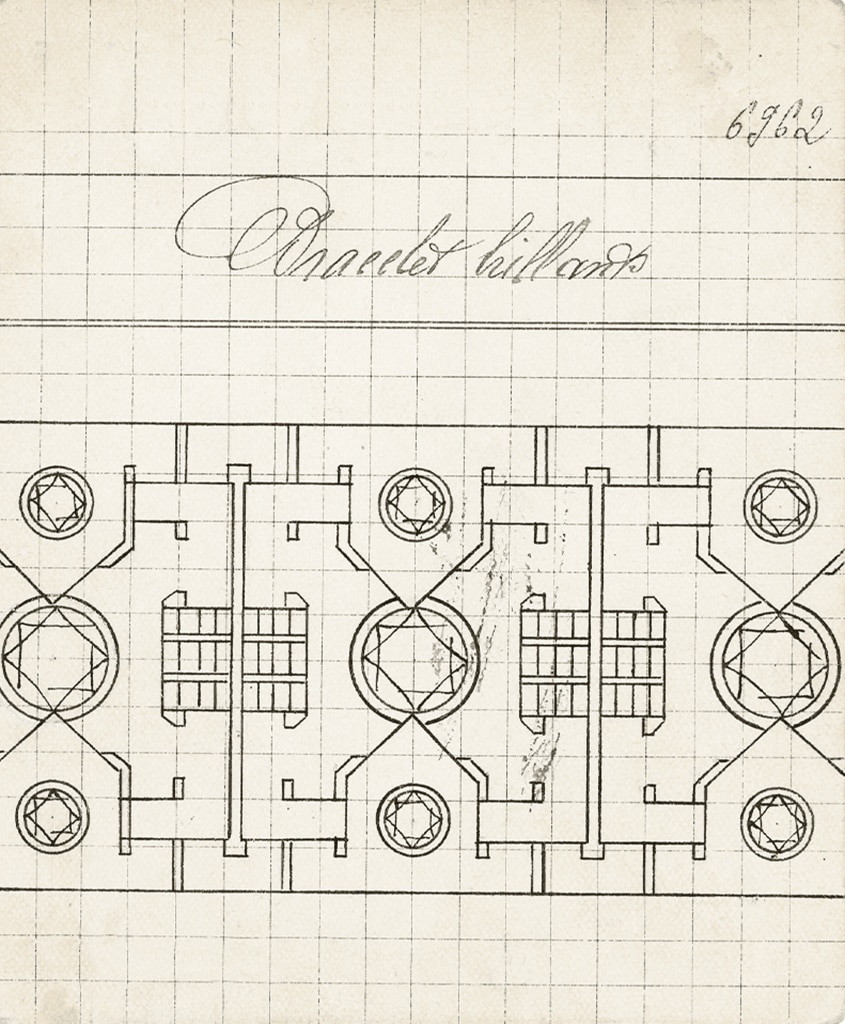

Thus it was that jewelers looked to this new repertory for the creation of pieces with “simple, robust forms, [and] clean lines,” enhanced by “pleasingly harmonious, strong colors.”15[Ministère du Commerce, de l’industrie, des postes et des télégraphes], Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes, Paris 1925: rapport général. Section artistique et technique (General Report: Artistic and Technical Section), Vol. IX, Parure (Finery) (Classes 20 to 24) (Paris: Librairie Larousse, 1927), 86. Van Cleef & Arpels favored the use of these motifs around “wide, flexible bracelets” that became “the fashionable jewelry item”16“L’Exposition des arts décoratifs,” Vogue Paris (June 1925): 49. of the decade. The jumble of overlapping straight lines was made possible thanks to the wide range of gemstone cuts available, whereby the round-shaped brilliant cut could be paired with the rectangular form of the baguette cut. The calibrated setting also gave gemstones geometric contours. The play of contrasting forms could be enhanced by a similar play of contrasting colors, which saw stones of a single color— either sapphires, rubies, or emeralds—forming a pattern on a pavé-setting of diamonds.

This play of contrasting colors was also found on band bracelets of more traditional design. In fact, the new geometric style, far from replacing Neoclassical decoration, existed alongside older styles. This is particularly noticeable in the ensemble created by Van Cleef & Arpels for the 1925 Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs. Two esthetics stand out in the projects that the Maison submitted to the selection committee: pieces in a naturalist style presenting “red and white roses,” and a series of flexible bracelets—two in white diamond jewelry and two adorned with sapphires— illustrating the use of Cubism in the jewelry arts.

PRODUCT CARDS OF BRACELETS

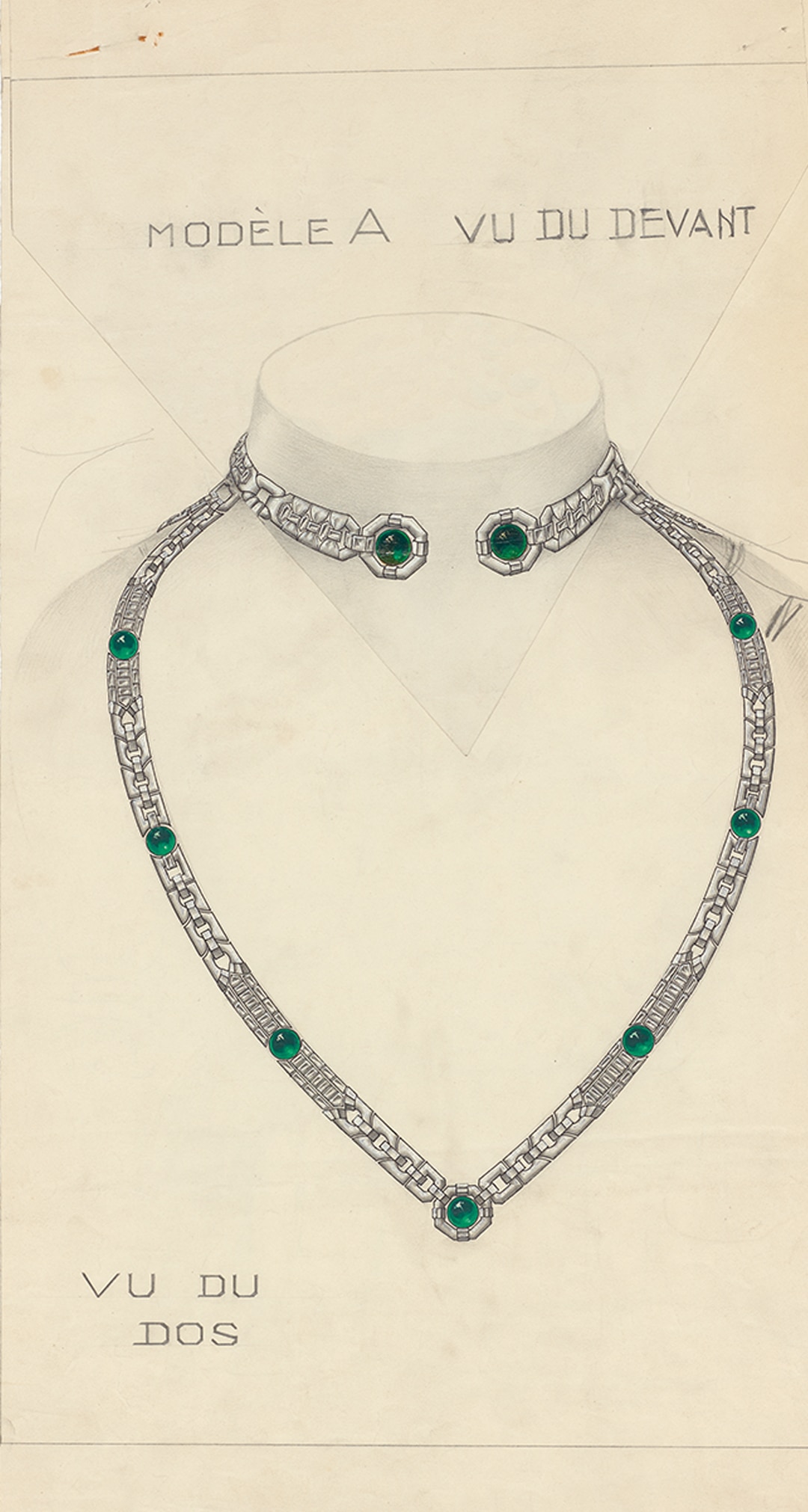

A fifth bracelet selected for the exhibition17This bracelet is illustrated in the exhibition’s general report. See: [Ministère du Commerce, de l’industrie, des postes et des télégraphes], Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes, Paris 1925: rapport général. Section artistique et technique (General Report: Artistic and Technical Section), Vol. IX, Parure (Finery) (Classes 20 to 24) (Paris: Librairie Larousse, 1927), 86. differed from the other four by the width of its band. This difference was also seen in another bracelet interspersed with emerald cabochons, the drawing of which also bears the stamp of the exhibition’s Class XXIV.18The Exhibition Class XXIV was dedicated to jewelry. Some of the preparatory gouachés conserved by the Maison bear the stamp of the “President of Class 24.” We cannot be certain, however, that this stamp is proof of the presentation of the piece represented in this drawing. Even if the rules of the exhibition mention that the admission of a work “will be announced beforehand on very detailed drawings,” we cannot state with certitude that this stamp is proof of the definitive validation by the category committee. While this piece is still stylized and uses just two colors, it provides a glimpse of a development whereby cleverly articulated, invisible rectangular units on the back of band bracelets gave way to clearly outlined links of larger size.

Jewelry at the 1929 Exhibition

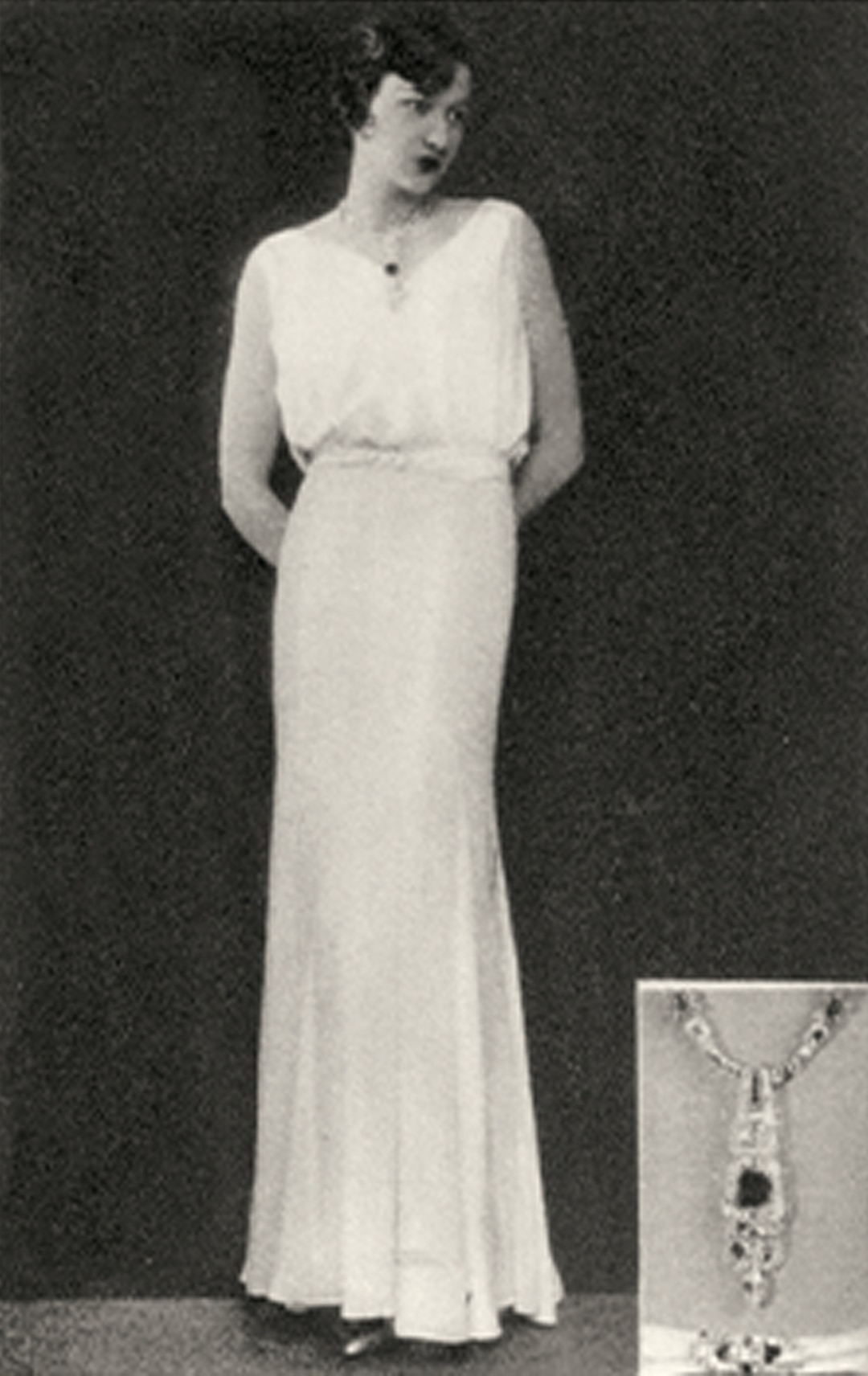

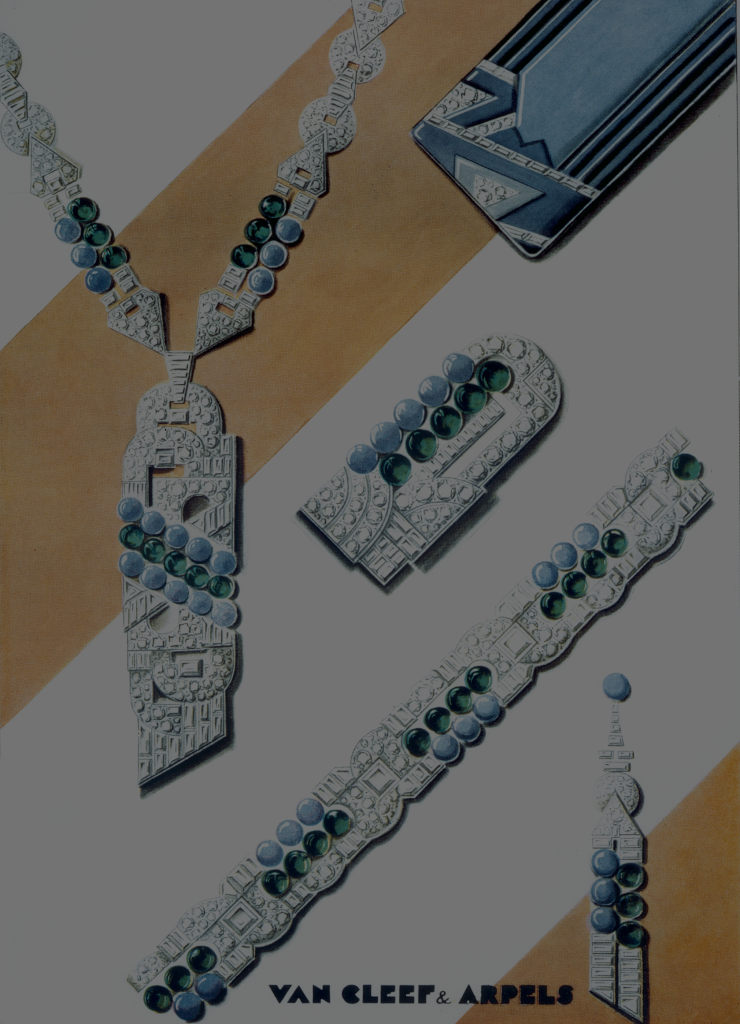

Following on from its success in the 1925 Exhibition, Van Cleef & Arpels focused its creativity on another event, the exhibition held at the Palais Galliera in 1929, dedicated to the jewelry arts, and gold-and silverwork. The Maison’s designs at that time were characterized by larger surfaces set with stones that exuded a sense of opulence. These pieces afforded a “richness of composition”19“La Somptueuse féerie des bijoux,” Vogue Paris (September 1930): 49. previously unseen in the Maison’s production, while retaining the “rigorous logic”20“La Somptueuse féerie des bijoux,” Vogue Paris (September 1930): 49. developed in the first half of the 1920s. “The taste for the stone in its own right was more marked” and in consequence, “it was used with less casing.”21“La Somptueuse féerie des bijoux,” Vogue Paris (September 1930): 49.

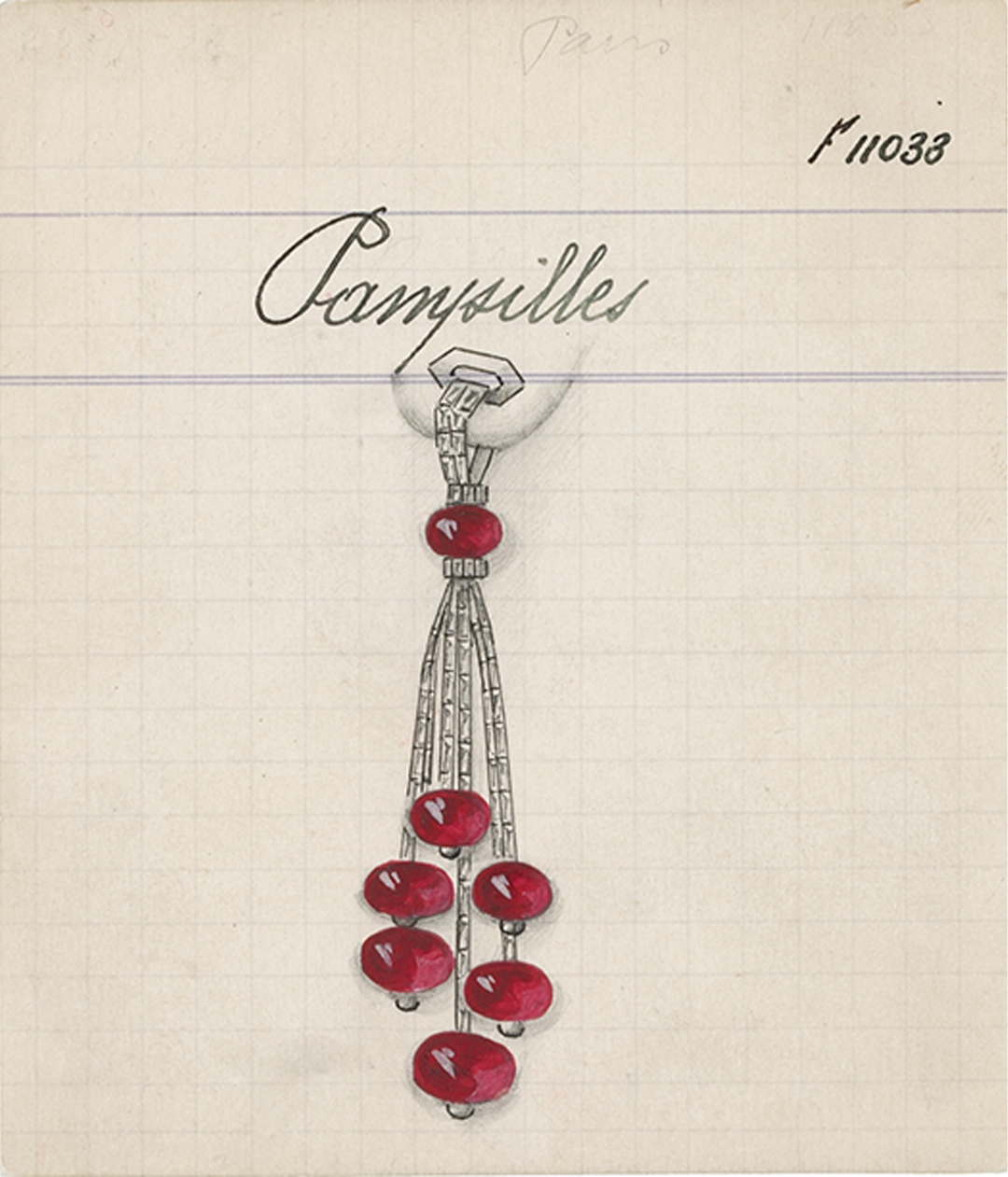

Closed-set cabochon stones and pear-shaped pendants were favored for having as little mount visible as possible. The volume of stones conferred a new three-dimensionality to the pieces of the late 1920s, albeit relatively timidly at first. They adorned pendant earrings, brooches, and necklaces that could be worn in many different ways.

One of the major innovations introduced by Van Cleef & Arpels in the late 1920s was a renewal of jewelry types that in turn led to an ingenious range of ways of wearing them. Bracelets could be buttoned around the upper arm like armbands, for example, thanks to an emerald cabochon, while the long necklace, popular in the early part of the decade, gave way, from 1928, to the “trend for shortening necklaces”22“La Somptueuse féerie des bijoux,” Vogue Paris (September 1930): 49.. Collerettes formed cascades of pear-shaped emeralds or rubies, both at the front and back of the piece. Ditto for short necklaces which had pendants front and back. Another novel manner of adorning the bust was the tie-necklace composed of a bejeweled strip with a trompe-l’œil knot.

Although the use of just two colors popular at the start of the decade could still be found, other stones such as turquoise and coral were being used by jewelers together with white diamond jewelry. More daring combinations were also experimented with, such as the turquoise and emerald used in a jewelry ensemble (brooch, bracelet, chain, and pendant) selected for display at the Palais Galliera in 1929. These innovations were actually a legacy from traditional eighteenth-and nineteenth-century jewelry. Attempts at simplification through the use of geometric forms were seen in white diamond jewelry arranged around central stones. At the same time, workers of precious metals within the Union des artistes modernes (UAM)—a movement founded in 1927—aimed to revitalize the metal arts by introducing previously unheard-of volumes into the jewelry arts.

Towards modernism

Thus, “to be modern [in 1929 was] not a question of making use of so-called modern formulae with an old approach to decoration,”23Raymond Templier, “L’Art de notre temps,” Revue de la Chambre syndicale de la bijouterie, de la joaillerie, de l’orfèvrerie de Paris et des industries qui s’y rattachent (1928): 15. but rather of questioning the methods inherited from previous centuries. For partisans of Modernism, “the market value should not be a factor in determining the beauty of a piece of jewelry.”24Jean Fouquet, “Du bijou” (On Jewelry), Revue de la Chambre syndicale de la bijouterie, de la joaillerie, de l’orfèvrerie de Paris et des industries qui s’y rattachent (1928): 17. They pointed out that “in their entirely praise-worthy desire to ‘be modern,’ [the] Galliera exhibitors allowed themselves to be hypnotized by the success of high jewelry.”25Jean Fouquet, “Du bijou” (On Jewelry), Revue de la Chambre syndicale de la bijouterie, de la joaillerie, de l’orfèvrerie de Paris et des industries qui s’y rattachent (1928): 17. It was not until the early 1930s with the repercussions of the Wall Street Crash on the French economy that the first traces of Van Cleef & Arpels’ adherence to Modernism were to be seen.

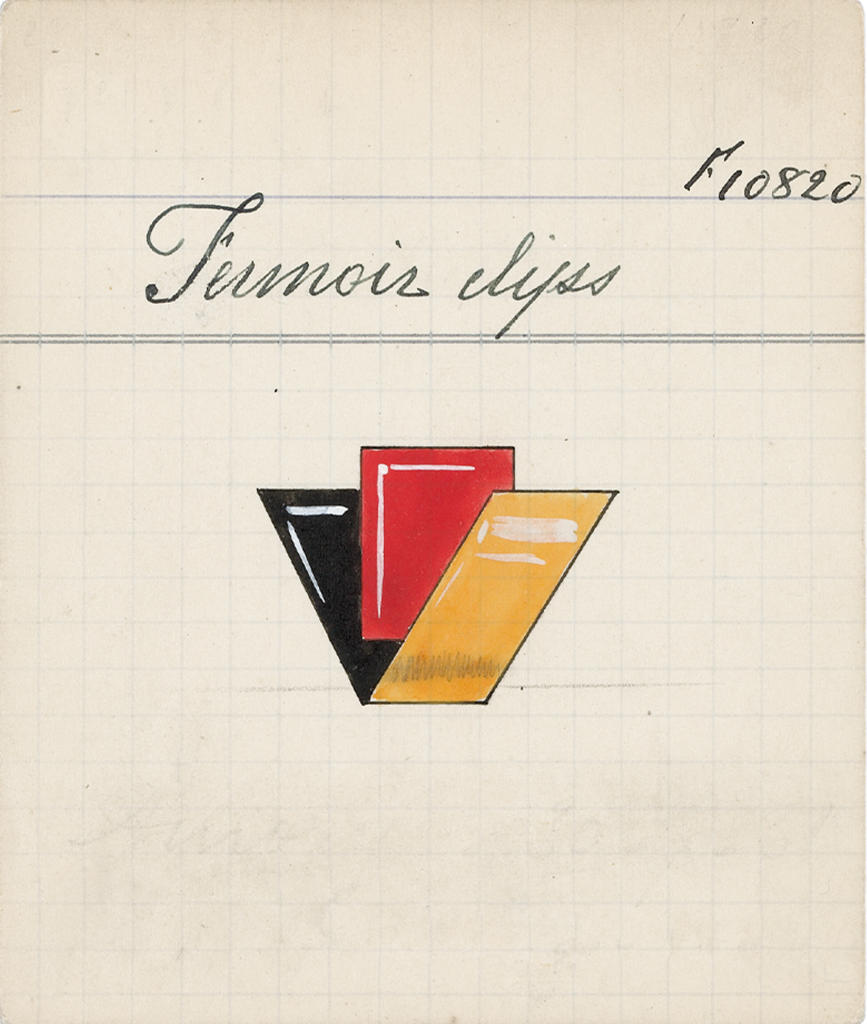

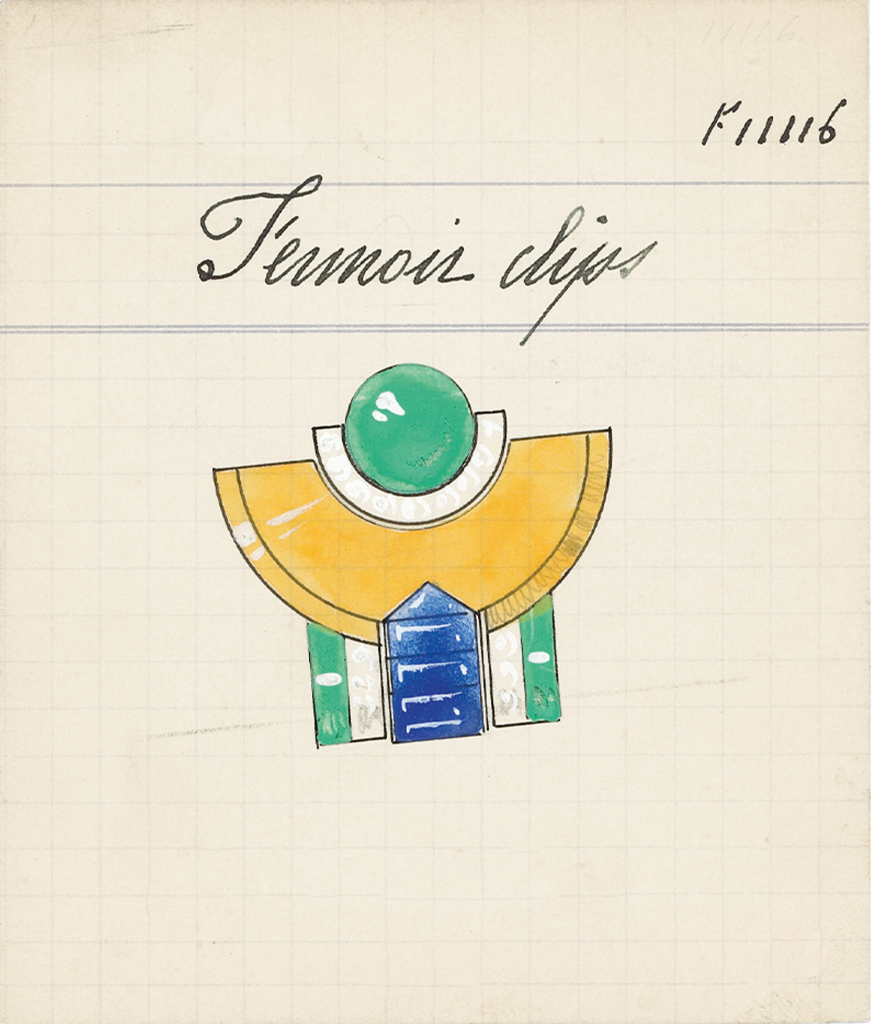

While sumptuous pieces of jewelry from 1929 were being dismantled barely a year after their creation in order to recover their precious materials, the Maison launched a so-called “fantasy” series of jewelry. This name described the use of stones and metal judged to be less precious. Such was the case for osmior, an alloy of gold, copper, nickel, and zinc imitating platinum, and of ornamental stones like lapis lazuli, malachite, and agate.

Furthermore, this production illustrates a revaluation of the “techniques of precious metal jewelers,”26Anonymous, “Nouvelle réflexions sur la bijouterie à Galliera,” Revue de la Chambre syndicale de la bijouterie, de la joaillerie, de l’orfèvrerie de Paris et des industries qui s’y rattachent (1929): 11. promoting the qualities of metal, whereas high jewelry promotes the art of setting stones. Purse clasps, in particular, provide sizable surfaces of metal that are not set with stones, but rather are enlivened with the rich “range of colors afforded by [alloys].”27Anonymous, “Nouvelle réflexions sur la bijouterie à Galliera,” Revue de la Chambre syndicale de la bijouterie, de la joaillerie, de l’orfèvrerie de Paris et des industries qui s’y rattachent (1929): 11. The notion “of contrasting values” was central to Modernist preoccupations: “The structure of jewelry should produce effects […] of light, color, […] planes, and volumes.”28Jean Fouquet, “Du bijou” (On Jewelry), Revue de la Chambre syndicale de la bijouterie, de la joaillerie, de l’orfèvrerie de Paris et des industries qui s’y rattachent (1928): 17.

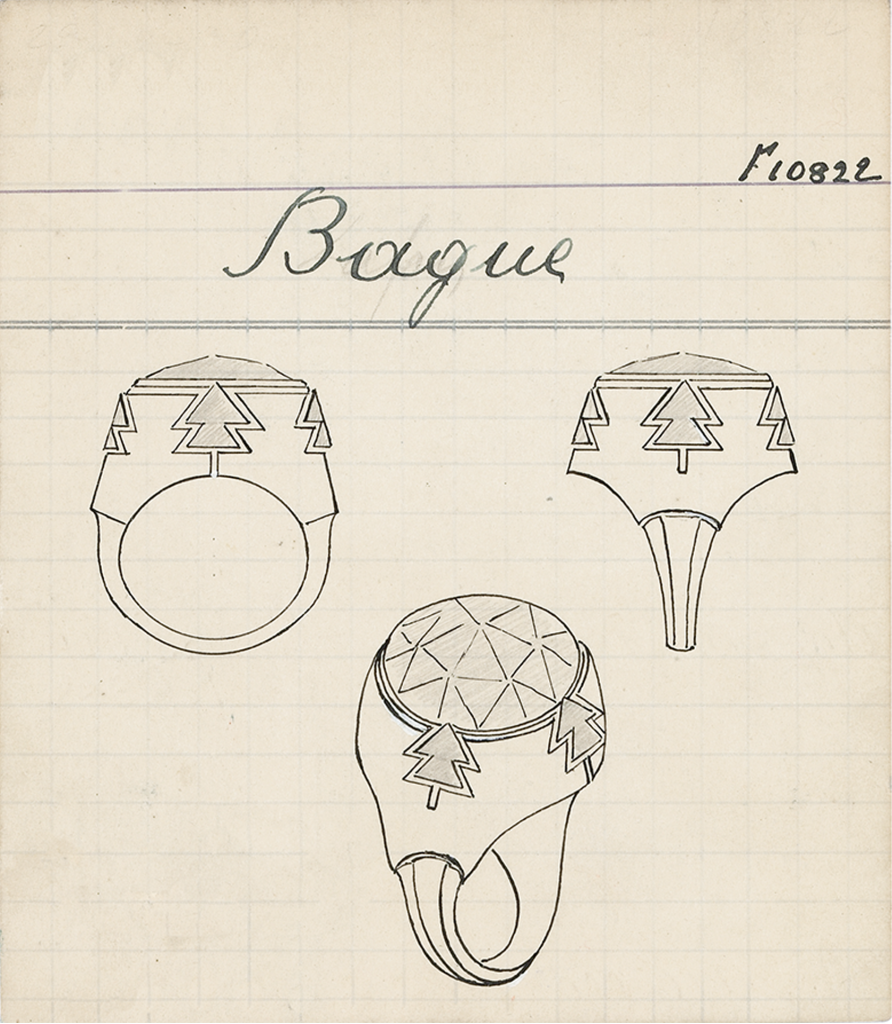

The three-dimensionality that was explored by jewelry in 1929 was heightened during the early years of the following decade: “A piece of jewelry should be seen as volumes in space and should be visible from every possible angle.”29Raymond Templier, “L’Art de notre temps,” Revue de la Chambre syndicale de la bijouterie, de la joaillerie, de l’orfèvrerie de Paris et des industries qui s’y rattachent (1928): 15. Which is why “one should not draw a piece of jewelry from the front only, but also in perspective, so that the planes can be seen.”30Raymond Templier, “L’Art de notre temps,” Revue de la Chambre syndicale de la bijouterie, de la joaillerie, de l’orfèvrerie de Paris et des industries qui s’y rattachent (1928): 15. Several sketches produced by the draftsmen working for the Maison in 1930 illustrate this, depicting rings shown from three different angles: front on, in profile, and from above.

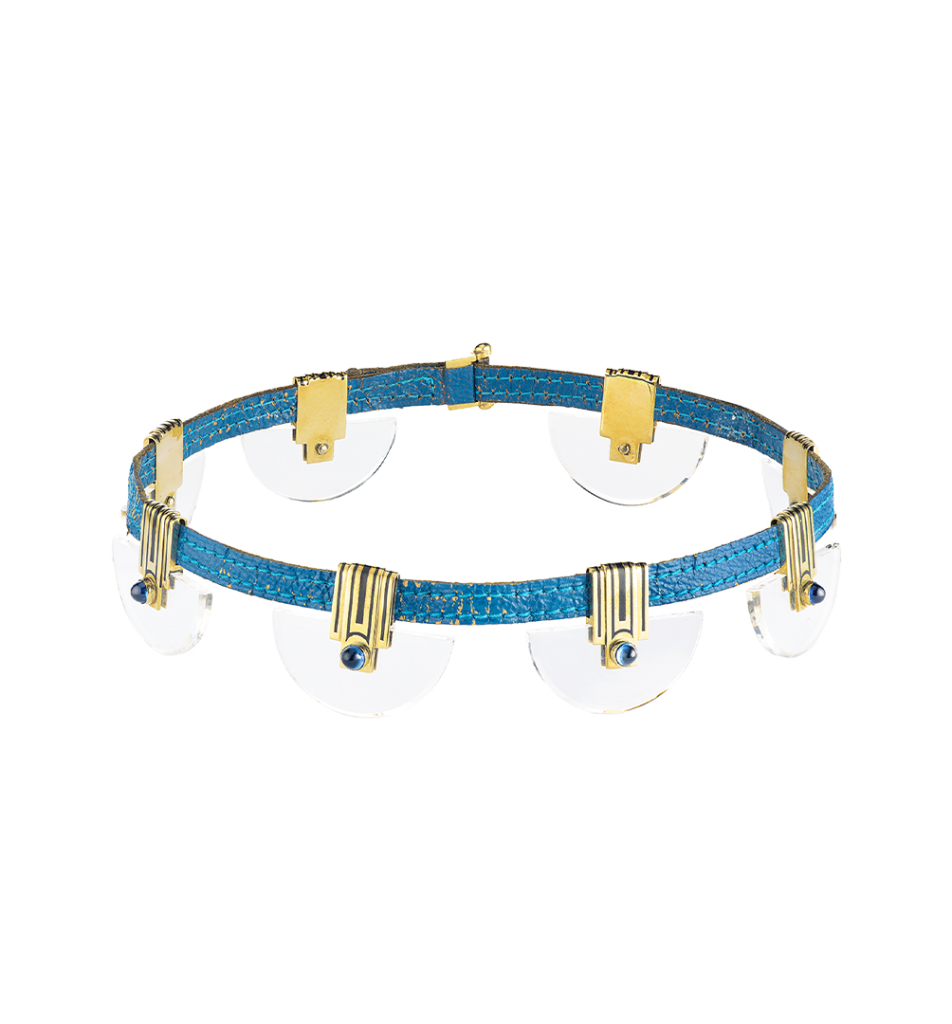

In short, modern jewelry calls for a communion of all artistic practices: “To be a jewelry designer, you have to be part painter, part sculptor, and even part architect, because it’s important for a piece to be studied […] for its color as well as its form.”31Éric Bagge, “Le Bijou moderne,” Revue de la Chambre syndicale de la bijouterie, de la joaillerie, de l’orfèvrerie de Paris et des industries qui s’y rattachent (1928): 19. This is illustrated by a group of costume chokers, created in 1930, in which color and form mutually define each other. These pieces offer an interplay between bold volumes and lively colors to enhance the effects of contrast, with ornamental stones in high relief adorning enameled metal motifs arranged on a strip of leather. Not many examples were purchased during the 1930s,32On the other hand, some models were acquired several decades later, in 1971 and 1973. perhaps because of their format combined with the avant-garde nature of the materials and shapes used. Like the jewelry sets produced in 1929, the unsold pieces were also subsequently dismantled and transformed into bracelets, considered less ostentatious than chokers.

The posterity of a style

The Art Deco movement was a major factor in the revival of the jewelry arts throughout both the 1920s and 1930s. In 1933, when the Maison redirected its production towards more strictly high jewelry compositions once again, after its short-lived Modernist phase, it looked to the geometric language of the late 1920s. Art Deco precious metal jewelry and high jewelry were to undergo a revival in the second half of the twentieth century, from the 1960s, inciting Van Cleef & Arpels to renew its production.