The first Salon dedicated to the jewelry arts and gold- and silver-work held at the Palais Galliera in Paris from May 28 to July 11, 1929, aimed to renew the success of the 1925 Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes.

The exhibition space was “more intimate” than the 1925 exhibition but was designed by the same architect, Éric Bagge, and aimed to create “perfect equality between [the] masters of the precious arts.” In the museum’s main gallery “a true temple to jewelry” was built, with “walls covered in silver and highlighted with gold.”1Henri Clouzot, “Au Musée Galliera. Les Arts de la bijouterie, joaillerie, orfèvrerie,” Le Figaro, arts supplement (June 13, 1929): 589–91. “The master jewelers presented […] their most recent creations [there].” These displayed “common traits— those that had proved their worth in 1925: simplicity of line, elegance of form, pleasing use of color, sobriety, equilibrium,” but were more assertively stated: “Far from coming to an end, the Modernist movement [had] just accelerated.”2Henri Clouzot, “Au Musée Galliera. Les Arts de la bijouterie, joaillerie, orfèvrerie,” Le Figaro, arts supplement (June 13, 1929): 589–91.

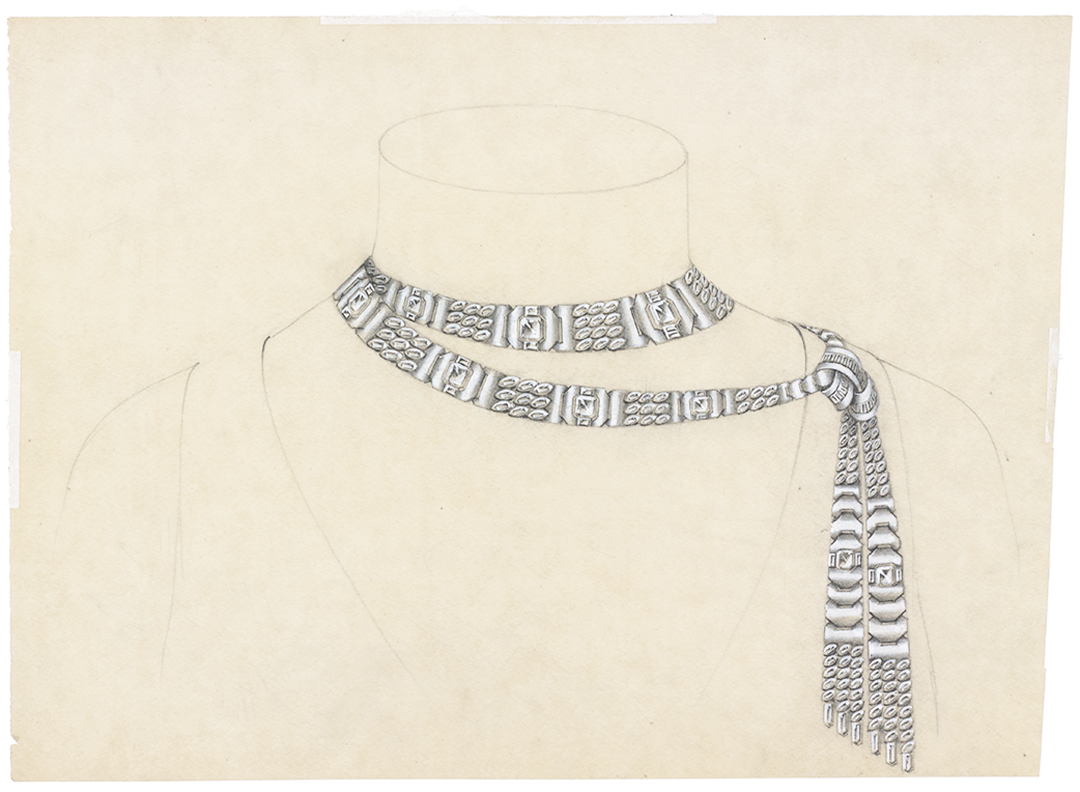

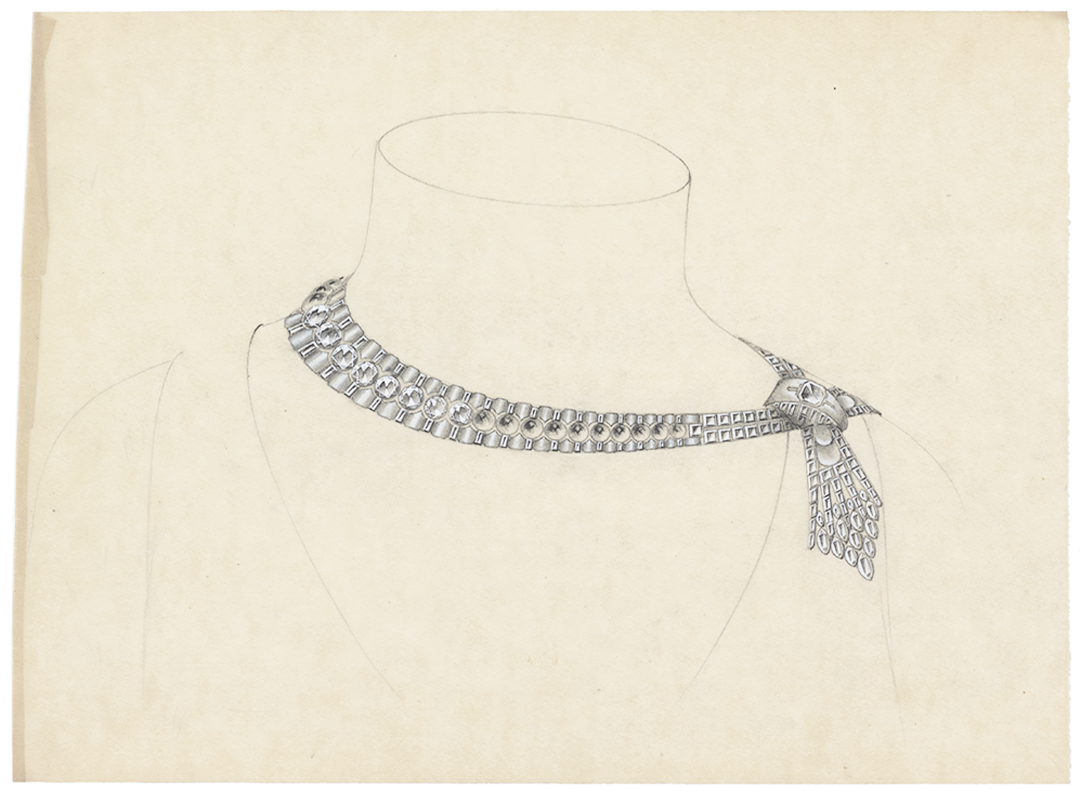

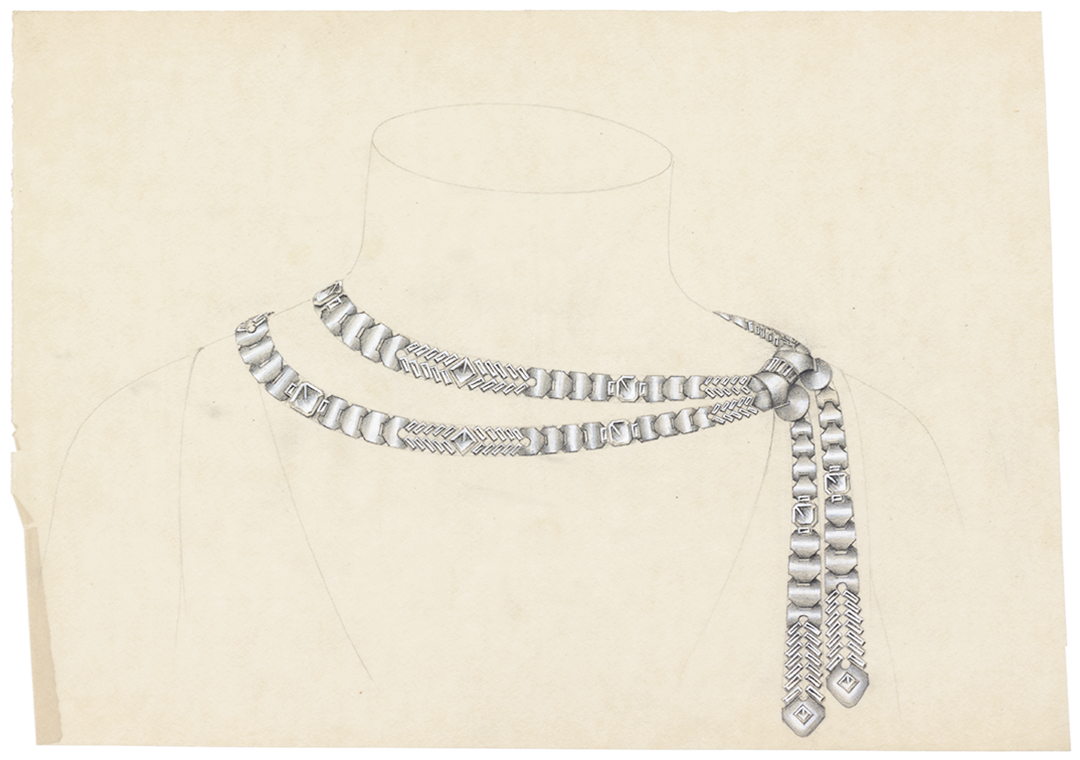

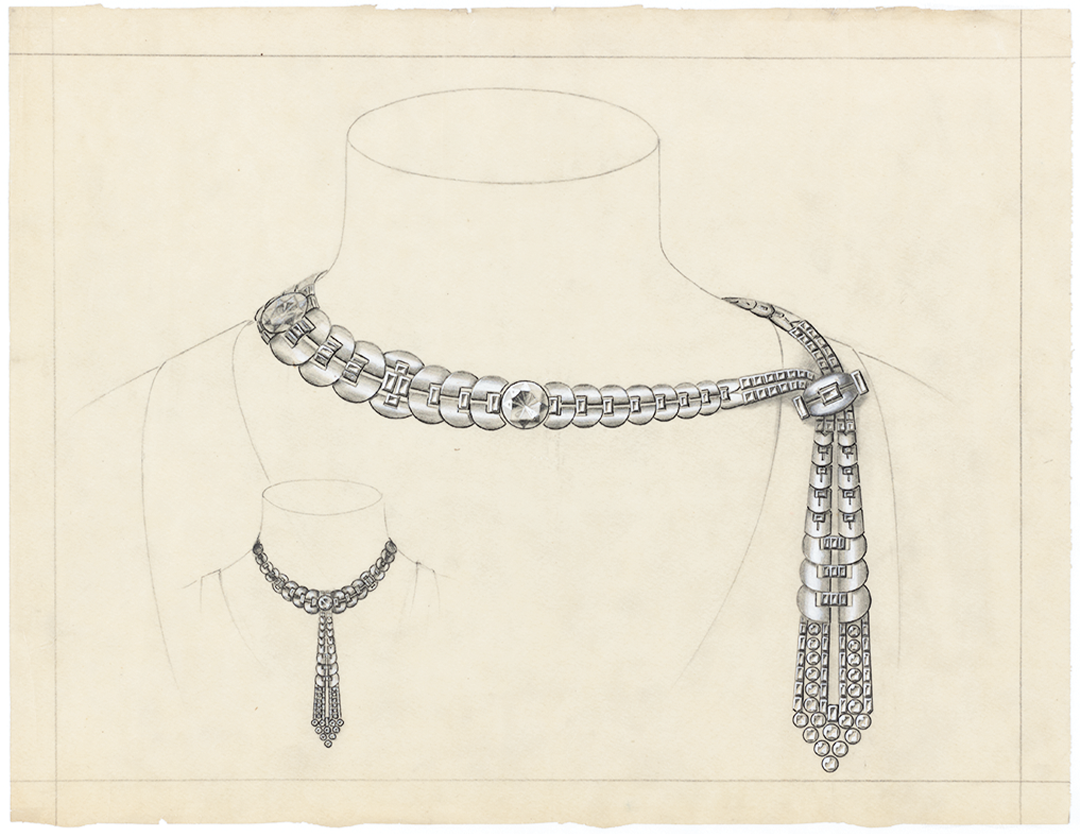

A new piece: the tie-necklace

The Salon also had a retrospective dedicated to precious metal jewelry from 1829 to the present, which not only illustrated its development over the previous century, but also enabled the public to observe that “the arsenal of elegance in 1929 is considerably less well stocked than that of a hundred years ago. Van Cleef & Arpels is the only jeweler to present a new genre of jewelry: a large tie-necklace knotted at the neck that hangs down across the chest with the fluidity of a ribbon.”3Henri Clouzot, “Réflexions sur la joaillerie de 1929,” Le Figaro, arts supplement (summer 1929): 685–88.

The prevalence of the jewelry

Van Cleef & Arpels also distinguished itself at this Salon with “imposing white jewelry,” which sometimes “[married the diamond] with emeralds” or “soft turquoises,” as seen in another of the Maison’s sets composed of a long necklace, a brooch, a bracelet, and pendant earrings. These four pieces of white diamond jewelry were notable for their geometric simplification and use of “less precious materials.”4Yvanhoé Rambosson, “Les beaux joyaux du Musée Galliera,” Comœdia (May 27, 1929).

The Birds clock

The art of stonecutting was also celebrated with a remarkable “piece of clockmaking worthy of a fairytale”.5Ruth Green Harris, “Paris sees interesting Modern Jewelry,” New York Times (August 11, 1929). This description refers to two birds in lapis lazuli perched on an ornamental basin resting on four agate columns, all placed inside a glass display case. The birds’ “beaks point out the time indicated by numbers set with diamonds”6Anonymous, “Detectives Watch Crowds at Exhibit of Costly Jewelry,” The Chicago Tribune and the Daily News (May 28, 1929): 3. inscribed on the edge of the basin. The two birds can move, which makes this clock the earliest example of a timepiece equipped with an automaton to be presented at an event of this importance.

A stylistic momentum restrained by the crisis of 1929

The organizers of this Salon, exclusively dedicated to the jewelry arts and goldsmithery, hoped that “more than a passing impression of taste and beauty” would remain from this event. The “lasting lesson[s] and guidance,”7Henri Clouzot, “Au Musée Galliera. Les Arts de la bijouterie, joaillerie, orfèvrerie,” Le Figaro, arts supplement (June 13, 1929): 589–91. as well as the creative impetus that should have resulted from it were arrested by the stock market crash, the first repercussions of which reached France in 1930. As a result, many of these opulent sets of jewelry were transformed during the following decade.