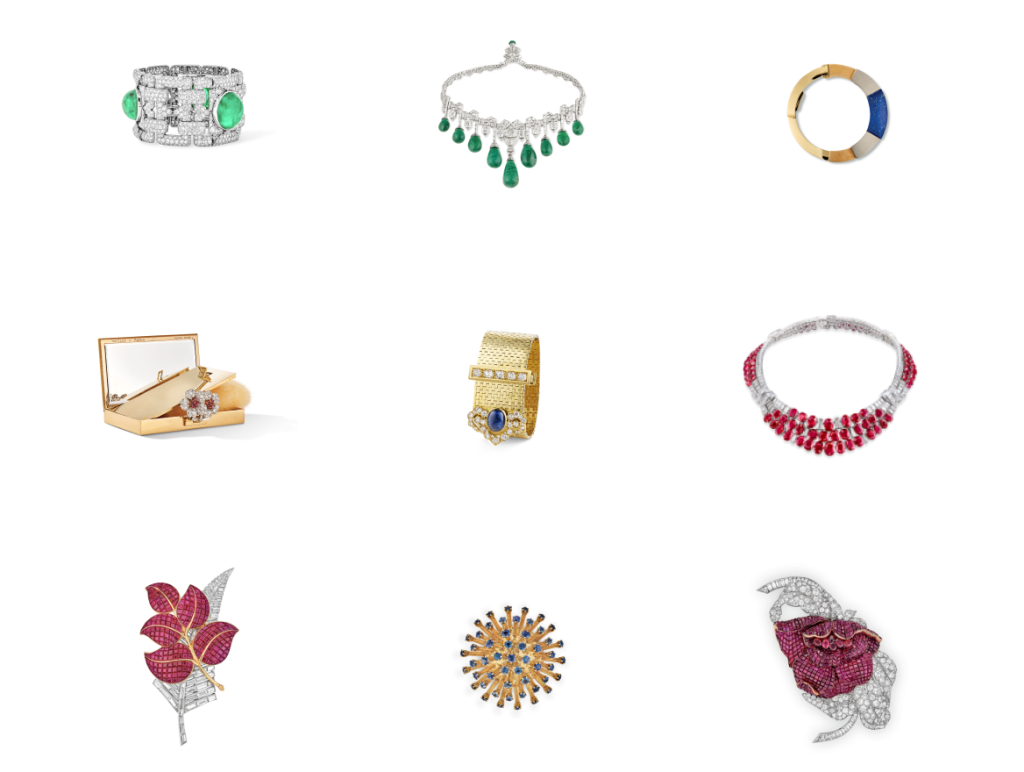

Radiator watch

Creation details

- Creation year 1930

- Stone Onyx

- Material Gold

- Usage Watch

- Dimensions 47 × 39 mm

Notice

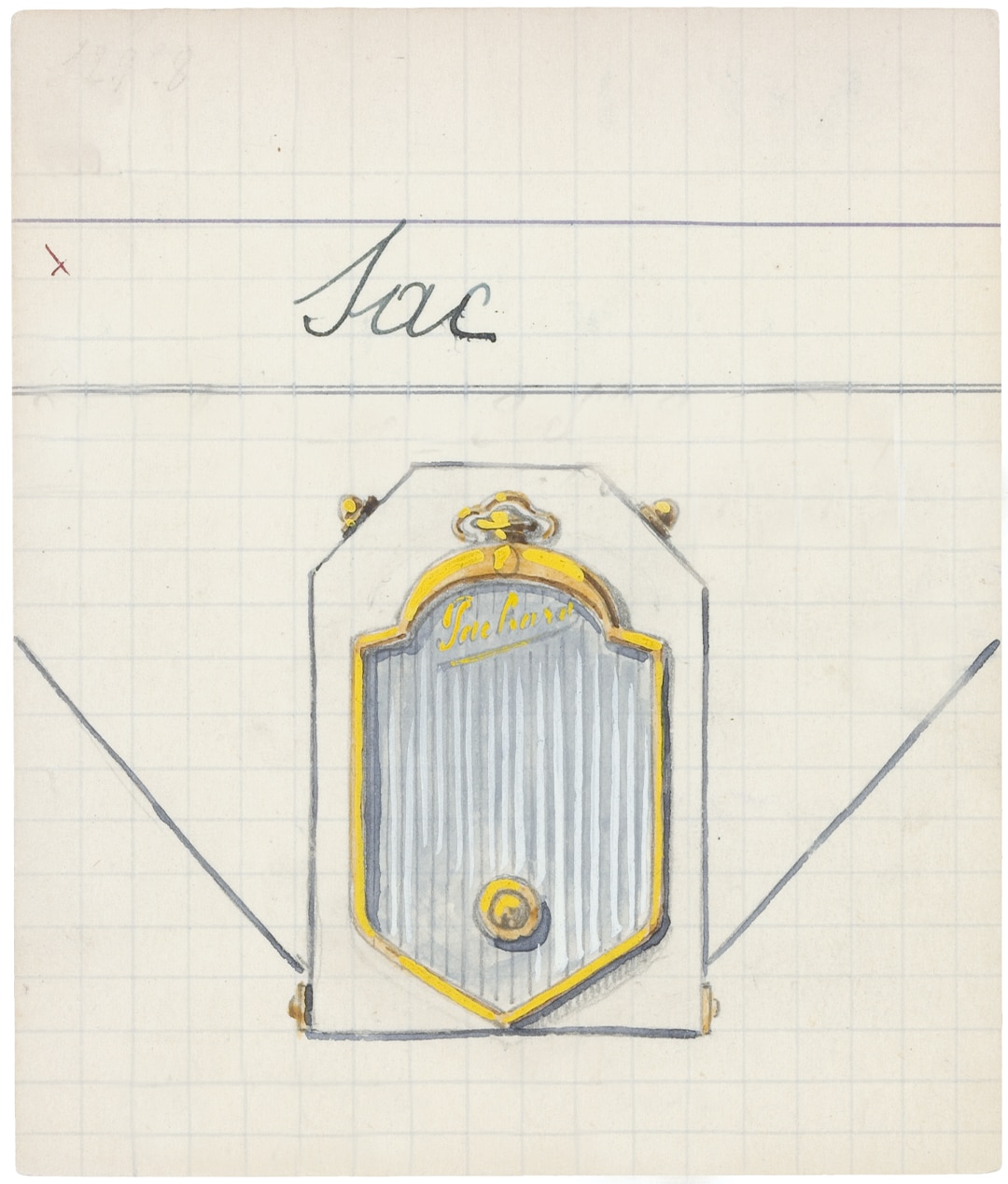

The Radiator watch was inspired by the principles underlying the mechanical arts and evokes both the world of watchmaking and that of automobiles. As its name indicates, this timepiece reinterprets the design of an automobile radiator and is typified by a novel system of “pivoting slats forming [a] protective screen [for the] dial”.1Patent for a “Watch with pivoting blades, forming a protective screen for the dial”, no. 691.683, filed by Georges Verger on March 10, 1930. Paris, INPI Archives.

The automobile’s radiator grille was thus replaced by strips of white gold, activated by push buttons decorated with onyx cabochons positioned either side of a case of yellow gold that accentuated the dial. The strips of this radiator grille extend beyond the casing to roll around a metallic cylinder that hides a fastening, thus enabling the watch to be used as a clasp for a purse. The watch case is sheathed in leather similar to that of the purse it is intended to adorn.

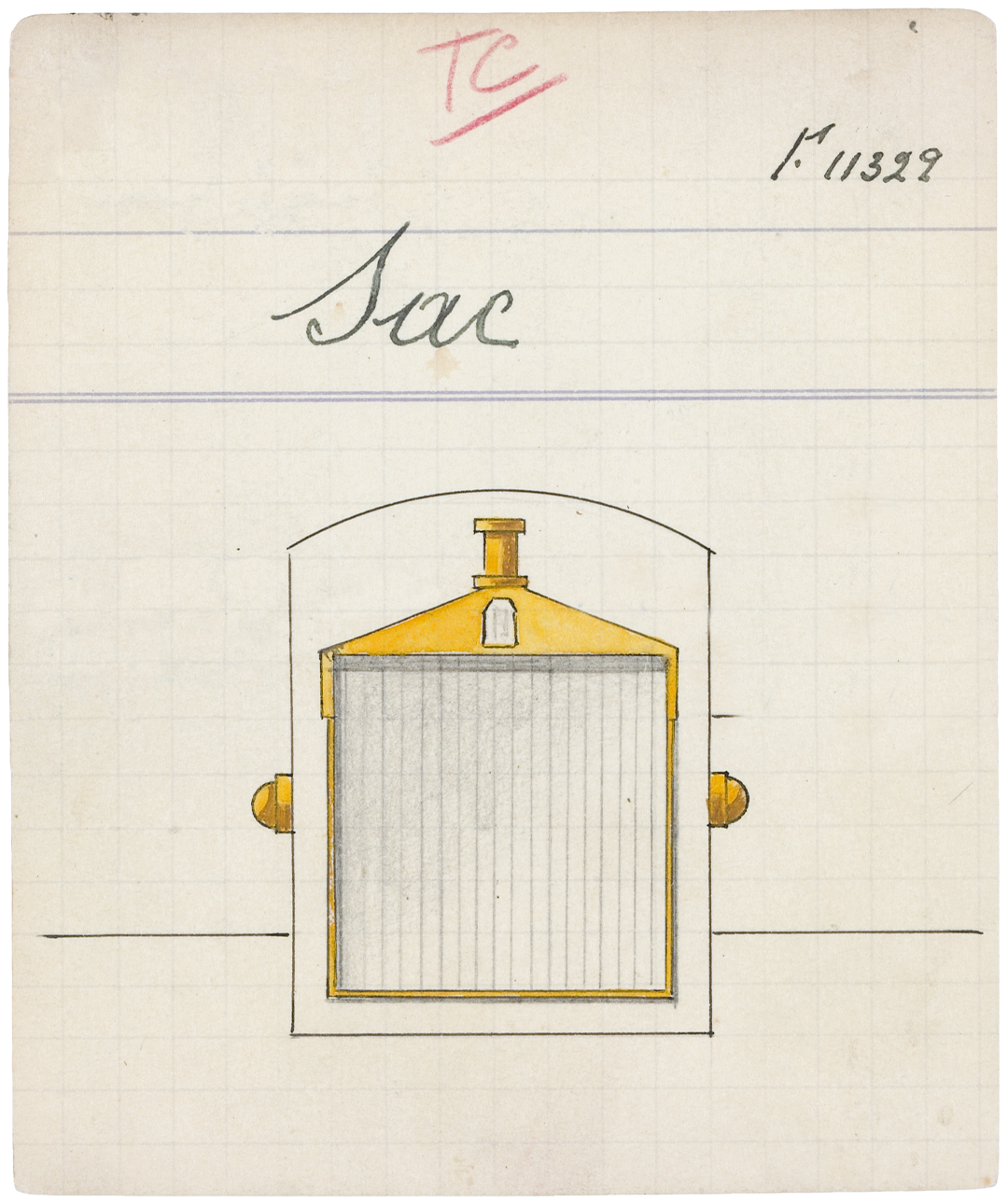

Automobile : iconography of modernity

Clasp-watches with pivoting strips were first seen in early 1931 as literal transpositions of automobile radiators. They faithfully reproduced the hood of a Packard automobile. A little later, a more pared-down model—all straight lines and devoid of any decoration—introduced a new technical contribution: a dial with “luminous numbers.” After a few months, Maison Van Cleef & Arpels abandoned these reproductions of automobile “fascia” in a radical simplification that retained solely the essential lines, as seen here in this piece.

The fascination for machines

During the early decades of the twentieth century, the art world was captivated by the beauty of machines. Of all the new industrial production, the automobile incontestably remained the star of modern life for many artists. The flowing lines of its bodywork and the speeds it achieved captivated the public imagination as it became more accessible during the 1920s. Back in 1909, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti was already singing the praises of the “racing automobile” which, “with its body decorated with large pipes, like snakes with explosive breath” suggested “a new Beauty: the Beauty of Speed.”2Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, “Manifeste du futurisme,” Le Figaro (February 20, 1909).

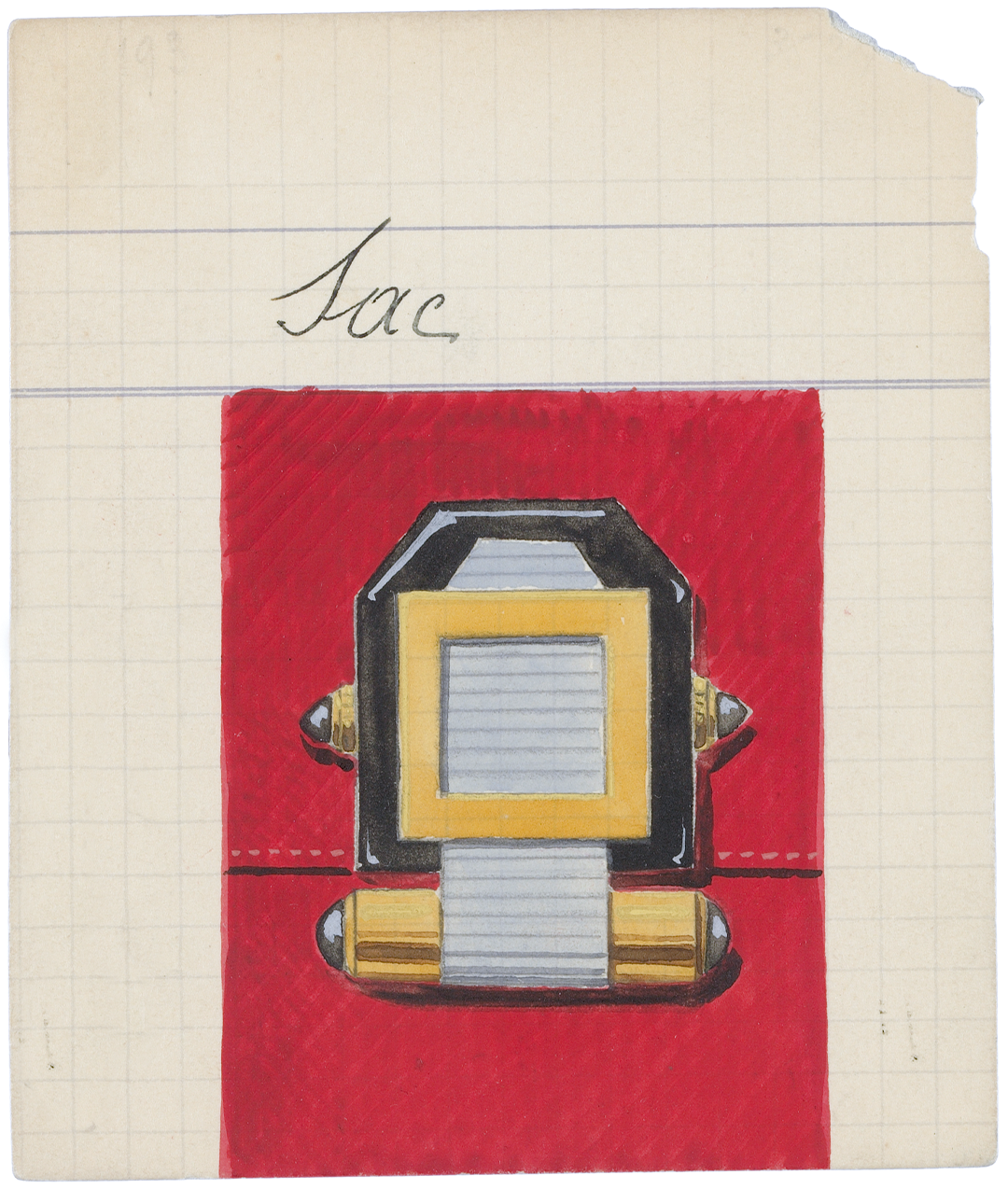

La simplification par le mouvement

The gradual simplification in the shape of the Radiator watch was in keeping with this new notion of beauty. As Jean Fouquet, another representative of the jewelry arts, said: “objects glimpsed at 75 mph become distorted and we only see their useful volumes.”3Jean Fouquet, “Du bijou”, Revue de la Chambre syndicale de la bijouterie, de la joaillerie, de l’orfèvrerie de Paris et des industries qui s’y rattachent, (1928): 15.

Automobile : women’s emancipation

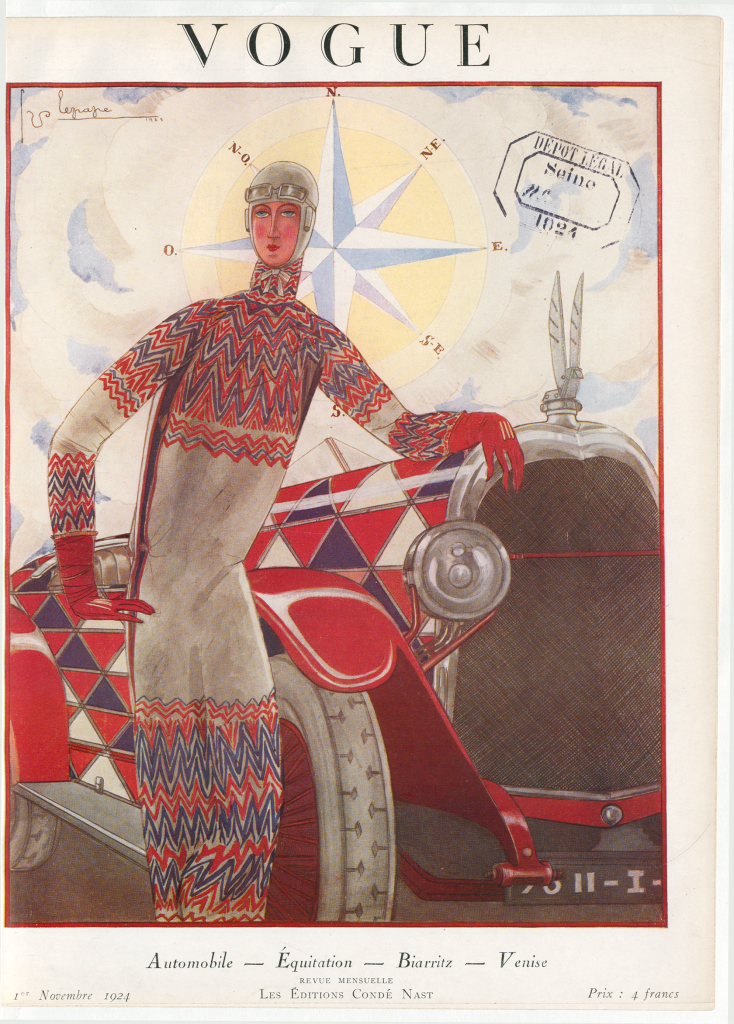

The Radiator watch, an accessory that enhanced a woman’s wardrobe, reflected, by its very modernity, the relative emancipation of women after the First World War. Women were now seen on the cover of Vogue alongside a Voisin automobile or posing for Robert Doisneau’s camera at the wheel of a Renault Vivasport, while advertising slogans proclaimed: “A modern women only rides in a convertible.” The automobile thus became a sign of modernity both in the daily lives of women and in their outfits.

To go deeper