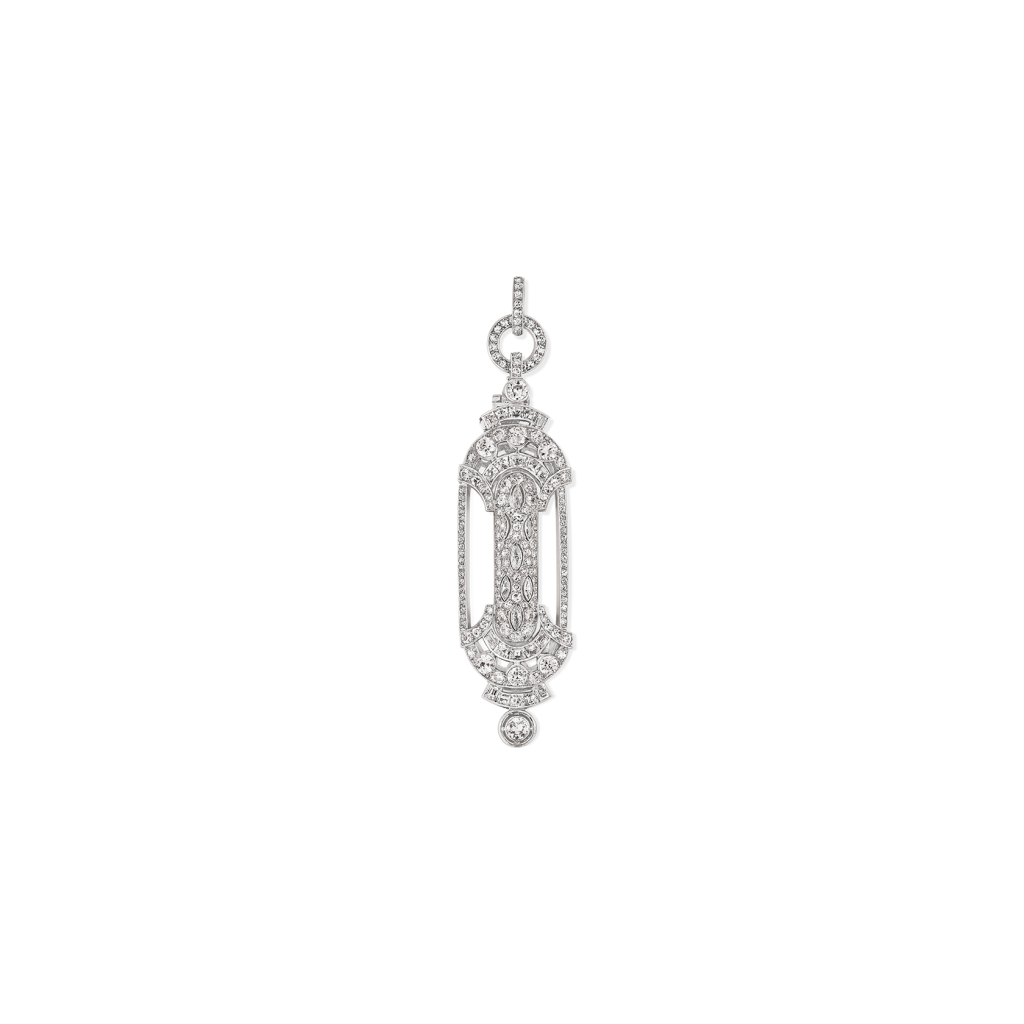

Lorgnette

Creation details

- Creation year 1927

- Stone Diamond

- Material Platinum

- Usage Other

- Dimensions 90 × 22.5 mm

Notice

This precious lorgnette, an accessory for enhancing vision, illustrates the range of the types of objects designed by Maison Van Cleef & Arpels in the 1920s. Its platinum frame is set with rows of brilliant-cut diamonds while the bridge, with its engraved geometric pattern, conceals the hinge between the two eyeglasses.

Once folded, these slip ingeniously into the handle, pivoting on an axis hidden by a closed-set diamond. The handle, entirely pave-set with brilliants and navette-cut diamonds, can be worn as a pendant thanks to two jump rings [see below]. Three round diamonds are arranged at both ends of the handle, framed by smaller brilliants and two rows of calibrated diamonds. A closed-set brilliant is symmetrically positioned opposite the one used as a pivot.

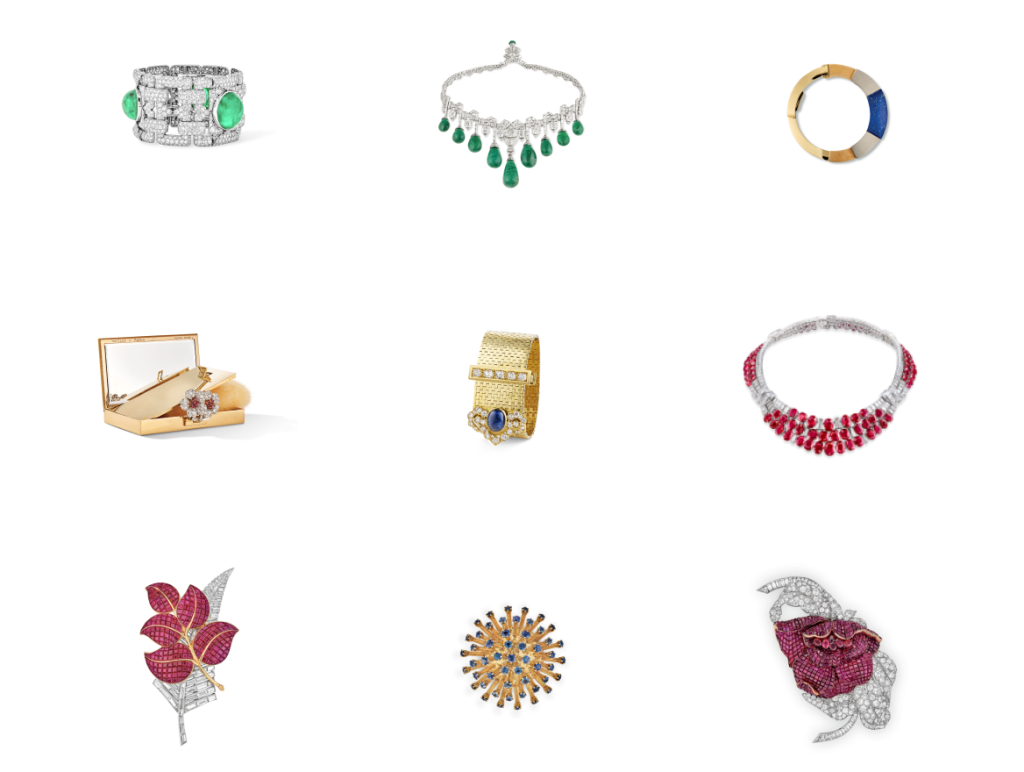

Diamond jewelry lorgnettes

Van Cleef & Arpels produced numerous lorgnettes during the early decades of the twentieth century. Most of them were made of platinum and diamonds, transforming an everyday object into a precious piece of jewelry. The production of precious lorgnettes illustrates the development of white diamond jewelry during the 1920s. The rose-and brilliant-cut diamonds in examples dating from the start of the decade gradually gave way to new cuts of gems: navette, baguette, and calibrated.

Between instrument and object of elegance

The lorgnette, an accessory uniquely for women, was made in various materials, from less expensive to more luxurious, depending on its uses. Versions in niello enamel and tortoiseshell, materials also used for all manner of objects made by spectacle makers, tended to be recommended for everyday use. Those made of precious metals and stones were reserved for rare occasions and for wealthy, fashionable women. Even if they were intended to correct vision, lorgnettes could also be used solely for decorative purposes. More often than not, they were “pretexts for vanity rather than serious instruments,”1Marcel Dufour, Quelques renseignements sur les verres de lunettes et leur emploi (Paris: A. Maloine Édietur, 1907), 33. which is why jewelers were tempted to transform an everyday object into a real jewel.

To go deeper