Émilie Bérard

The mystery set, an extraordinary technical achievement, is the result of an age-old quest traversing the entire history of French jewelry-making. The art of gem setting is thousands of years old.

It consists of folding metal around polished or cut stones in order to fix them securely to a metal support. The technical progress made in cutting gemstones during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries brought about a distinction between the work of goldsmiths and that of jewelers. The latter accentuated the stones by setting them on an openwork precious metal mount that let the light through. So-called “modern” French jewelry was thus born. From then on, craftsmen continually endeavored to lighten the silver and gold mounts, but it was not until the end of the nineteenth century that the first mounts or “carcasses”1The word “carcass” refers to the metal mount of a piece without its stones, and is frequently found in nineteenth-century jewelry archives. using platinum claws were to be seen. The early twentieth century was marked by the real advent of platinum, which gave jewelry designs hitherto unforeseen lightness. Despite these technical advances, the desire to create jewelry “relieved of all visible metal”2Advertisement, 1951. Paris, Van Cleef & Arpels Archives. remained omnipresent.

A long genesis

In the first half of the twentieth century, a number of Maisons and jewelry workshops sought to develop a system of invisible mounts, including Chaumet, Cartier, Boucheron, and Van Cleef & Arpels, as well as the Langlois, Guérin, and Rubel workshops. The process began on August 17, 1904, when Jean-Baptiste Chaumet registered a patent. Nearly thirty years later came Maison Cartier’s turn to register a patent, on October 22, 1932.3Patent no. 753 508: “Mode de fixation des bijoux sur leur monture” (Method of fixing jewels to their mount). Competition was stiff; neither of these two patents, however, appears to have been exploited on a large scale.

Collaboration with the Langlois workshop

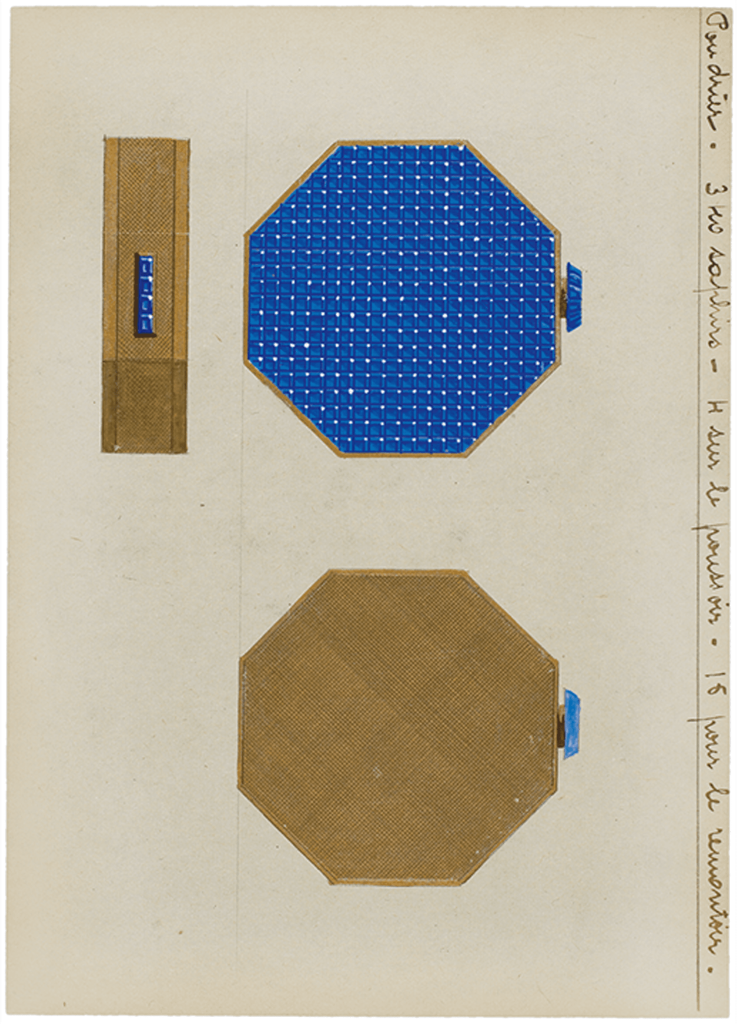

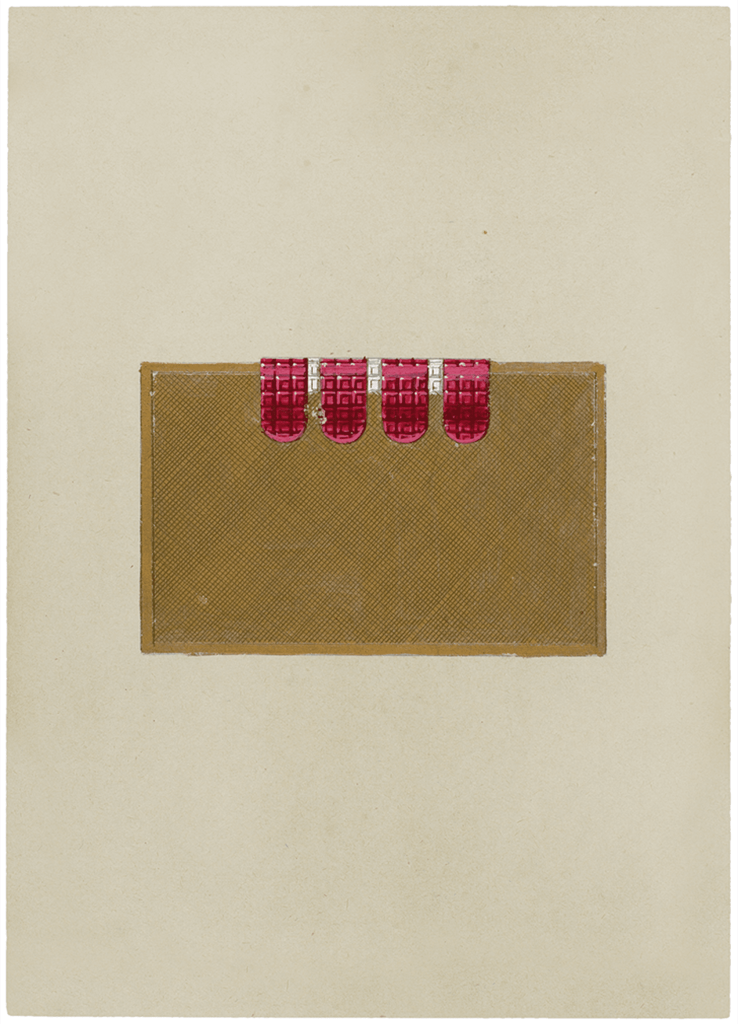

The early 1930s brought with it shifts at Van Cleef & Arpels, as the Maison developed new creative momentum and expanded internationally. These changes were closely linked to the partnership between Van Cleef & Arpels and Atelier Alfred Langlois. The Langlois workshop was located at 243 Rue Saint Martin in Paris’ third arrondissement, and was specialized at that time in making boxes and nécessaires. It worked with all the famous Maisons of the period, such as Boucheron, Cartier, Lacloche Frères, Mauboussin, Marchak, Ostertag, and Van Cleef & Arpels. The friendship that developed between Alfred Langlois and Alfred Van Cleef led to a creative partner- ship that was officialized on July 1, 1932,4This collaboration was upheld through to 1996, when Atelier Langlois became part of Maison Van Cleef & Arpels. when Alfred Langlois signed an exclusive contract with Van Cleef & Arpels, which, until then, did not have its own workshop. In exchange, Alfred Van Cleef became a trustee of Langlois.(5) The latter was responsible for making the Minaudières and mystery set jewelry, two emblematic and technically ambitious lines with a strong visual identity that, from then on, were part of the Maison’s creative and marketing strategy.

Minaudière

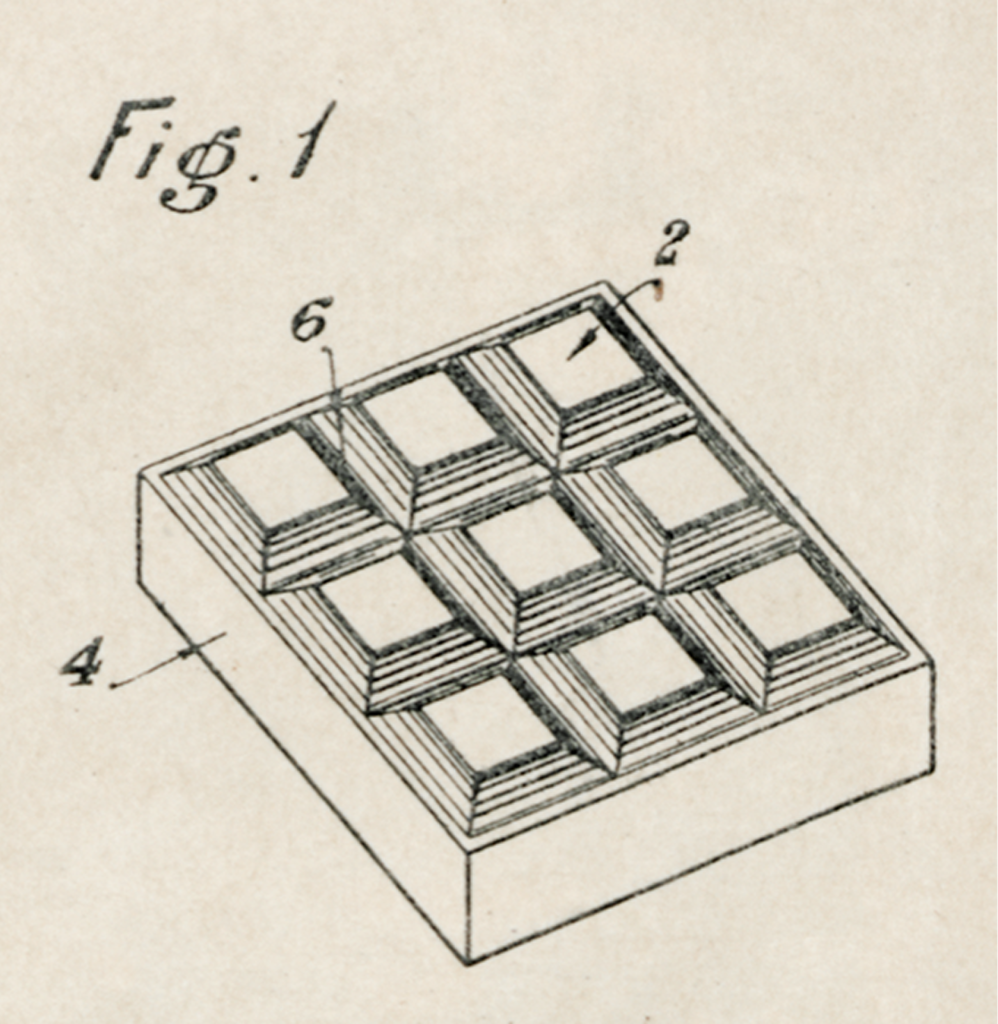

Patent registration

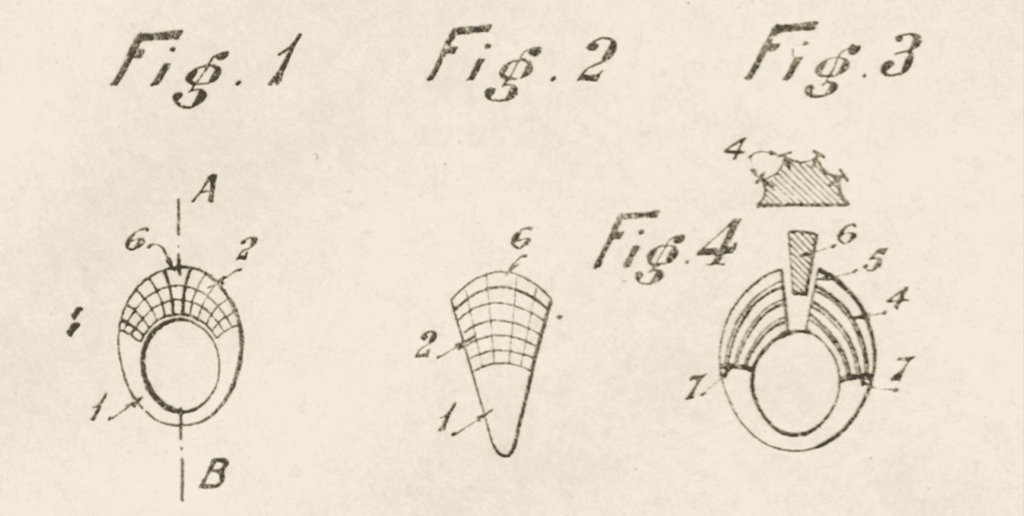

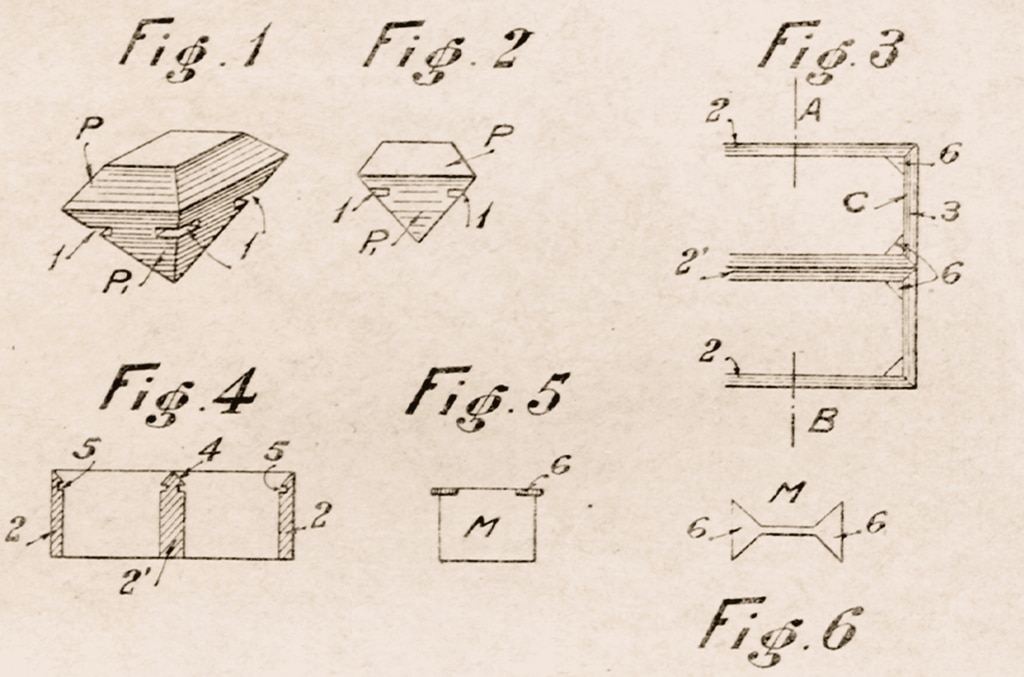

On December 2, 1933, it was Van Cleef & Arpels’ turn to register a patent for adorning boxes with invisible settings, based on the technical research carried out by the Langlois workshop. The patent was titled “method for mounting precious stones,” and was issued on March 19, 1934, and published on May 31 of the same year. It was explained as follows: “A method for mounting stones for jewelry, characterized by the fact that the precious stone has hollow parts into which relief parts of the mount are inserted, thanks to which the mount is largely or entirely hidden within the stone.”5Patent no. 764 966. The same patent was registered in Great Britain on September 25, 1934,6Patent no. 432 074. demonstrating Van Cleef & Arpels’ eagerness to include this invention in its conquest of new markets.

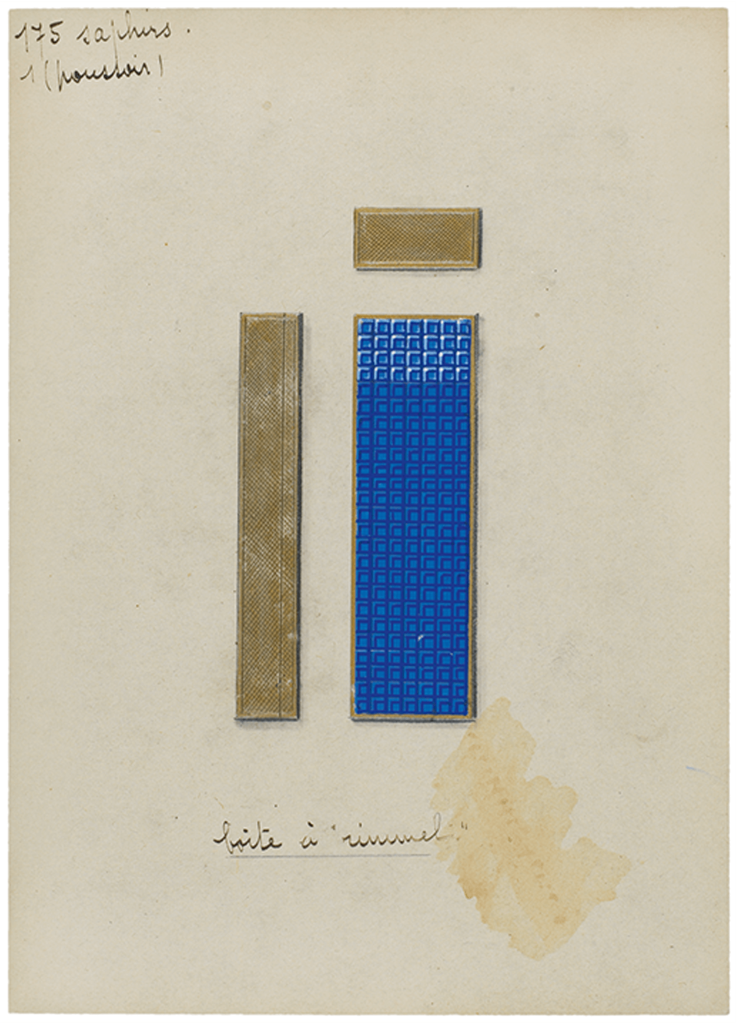

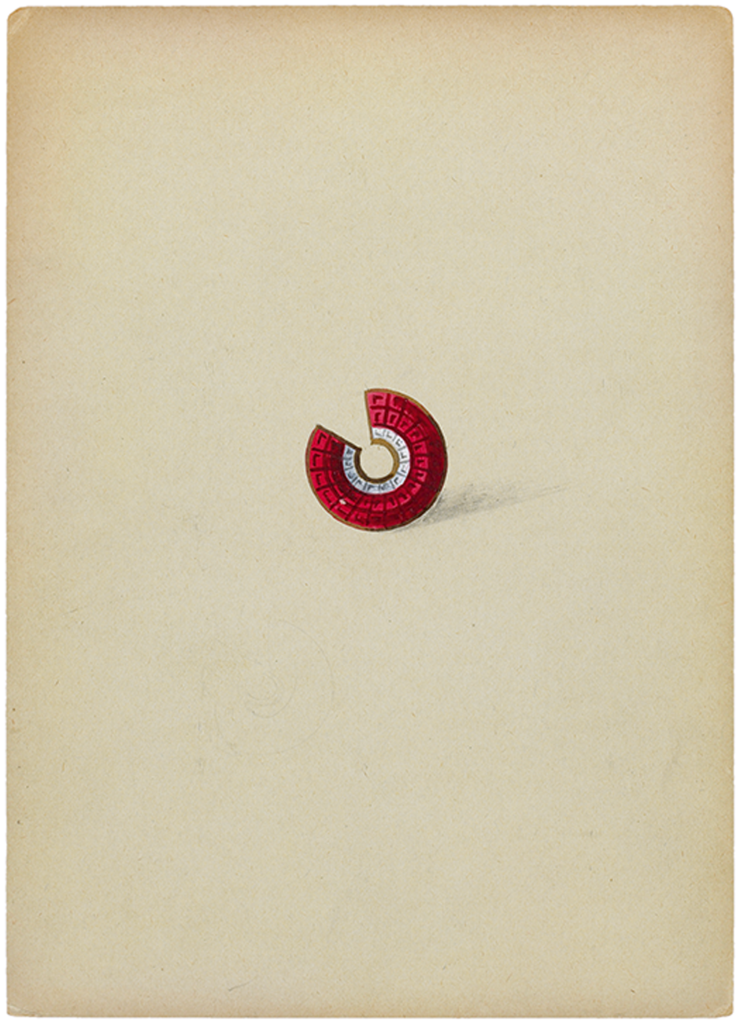

The term “mystery set” did not yet exist. Between 1933 and 1934, the expression “new set” or “invisible set” is found in the Maison’s archives. It was not until December 14, 1936, that the name “mystery set”7Patent registration no. 311 911. was registered. The first pieces to use this innovative technique were objects with flat surfaces: cufflinks, powder compacts, boxes, and Minaudières. The “creole earrings” were the first to use it on a curved surface.

The evolution of the mystery set

On February 13, 1936, the mystery set technique was improved and a patent registered in the name of the “Société Van Cleef & Arpels (S.A.R.L.)”. It aimed to perfect the method from 1933, and described the origin of what was a crucial element for a mystery set piece of jewelry: the “key,” nowadays known as the “porte” in French (“door”). “The invention aims to perfect a kind of mount for precious stone motifs in which the various stones are maintained parallel, or nearly parallel, to each other between bands or strips; the invention being characterized by the fact that part of the motif, suitably chosen, called the key, is immobilized in such a way that when this key is removed, it is easy to insert the stones for the rest of the motif, either by sliding them between the strips, or by inserting them between these strips thanks to their malleability, after which the key can be put back in place and secured, thereby blocking the stones that are already mounted and preventing them from popping out of the mount again.

In a variant that is preferable, the key is positioned so that its surface can be covered in stones, which, once the key is in place, form an integral part of the planned motif, so that the key becomes completely invisible, and the piece is perfectly homogeneous.”8Patent no. 801 863. The invention of this system was crucial and marked an important stage in the creative process, extending the range of possibilities; no longer limiting it to flat surfaces but encouraging the creation of mystery set pieces with volume. In line with the Maison’s desire for commercial development abroad, this patent was registered in Germany,9Patent no. 669 580, registered on March 20, 1936. then Great Britain,10Patent no. 454 770, registered on March 31, 1936. and lastly the United States.11Patent no. 2 119067, registered on May 1, 1936.

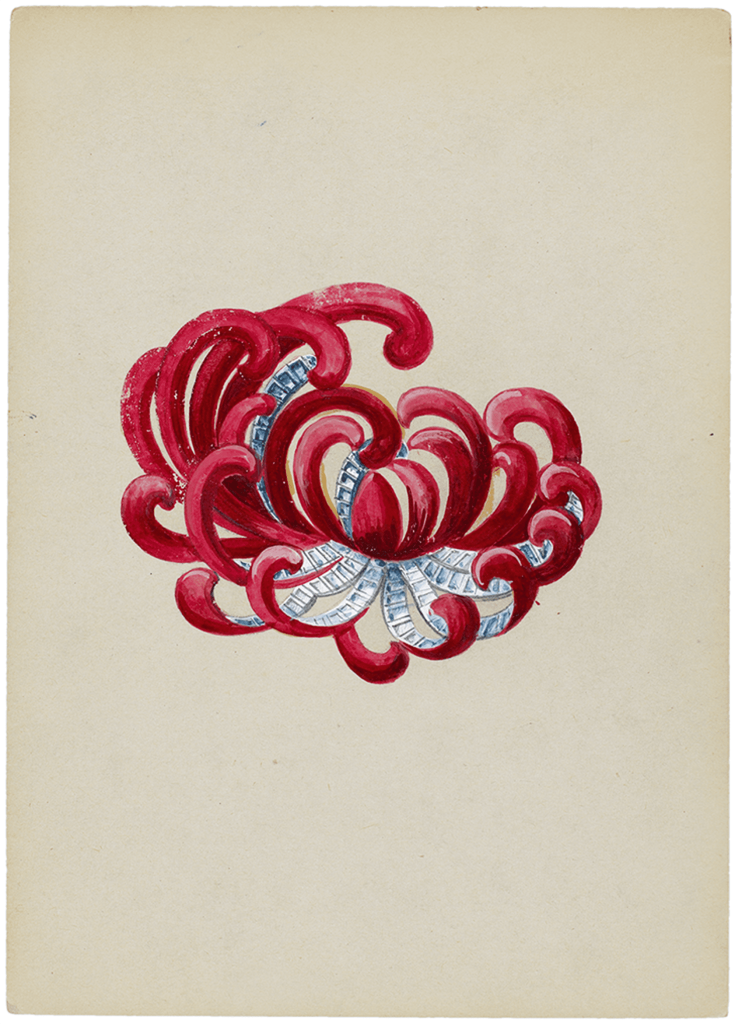

Chrysanthemum clip

The third patent

This second patent was completed by a third one,12Patent no. 802 367. dated February 24, 1936. “The invention is intended to be a method of mounting precious stones characterized by the fact that the stones are simply placed on the mount, fixed by means of pieces with projections that fit into the notches made in the stones, on one side, and into the compartments made in the mount, on the other, the latter being invisible once the stones are completely mounted.”13Patent no. 802 367. This third patent was only registered in France.

Volume and curves

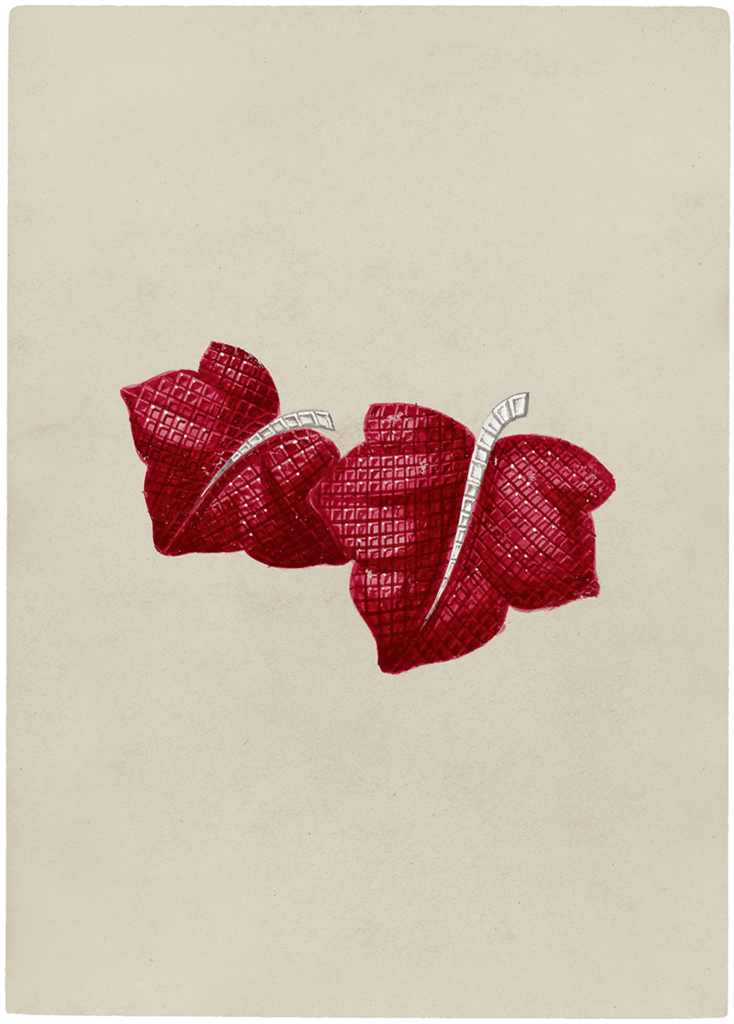

Between 1935 and 1937, each new piece that used the mystery set technique had more volume and curves than its predecessor. As the three figures of the second patent illustrate, the Boule ring was the first three-dimensional piece to use the mystery set technique. From 1935, the Langlois workshop made models of the Boule ring with sapphires, emeralds, and rubies. That same year, a Three-Leaf clip was created in rubies; it was the first mystery set piece directly inspired by nature. In 1936, a Palm Leaf clip was sold, while Wave bracelets were made in rubies, then sapphires. Each of these models represented new technical prowess, breaking entirely new ground.

The choice of gems

In the 1930s, emeralds, rubies, and sapphires were the gems of choice for mystery set creations. Thereafter, emeralds were less frequently used due to their fragility, the lack of a regular supply, and the difficulty in finding stones of the same color. Diamonds were also dismissed because of their hardness, which made them difficult to cut, and their clearness, which allowed the mount to show and cause a “black effect.” Several pairs of cufflinks using topaz were made in the late 1930s,14Product cards. Paris, Van Cleef & Arpels Archives. but this gem remained an exception due to its fragility. The batches of stones used for the mystery set technique were carefully assembled, classed by material and color. These batches “existed on a day-to-day basis” in so far as the gems were used for repairs and matching other stones.

Like a building made of cut stone, the gems used for the mystery set technique are calibrated squares recut by the lapidary. The square form is the one that loses the least material possible. Collecting the stones is difficult, as each gem is individually selected. The selection criteria are color, thickness of the “pavilion,” and purity. For pieces made of rubies, there is a selection process whereby up to three shades of color are gathered, which, when juxtaposed, give a velvety finish typical of the mystery set. The pavilions of gems have to be high in order to accommodate the etched lines where the rails have to be slotted. The almost total absence of inclusions avoids unpleasant surprises when recutting. Lastly, the pairing must be perfect: the gems must all have the same color intensity, and assembling them together requires time. This selection process for the mystery set is done solely with the naked eye, placing the gems in a row and looking at them through their “table” facet.

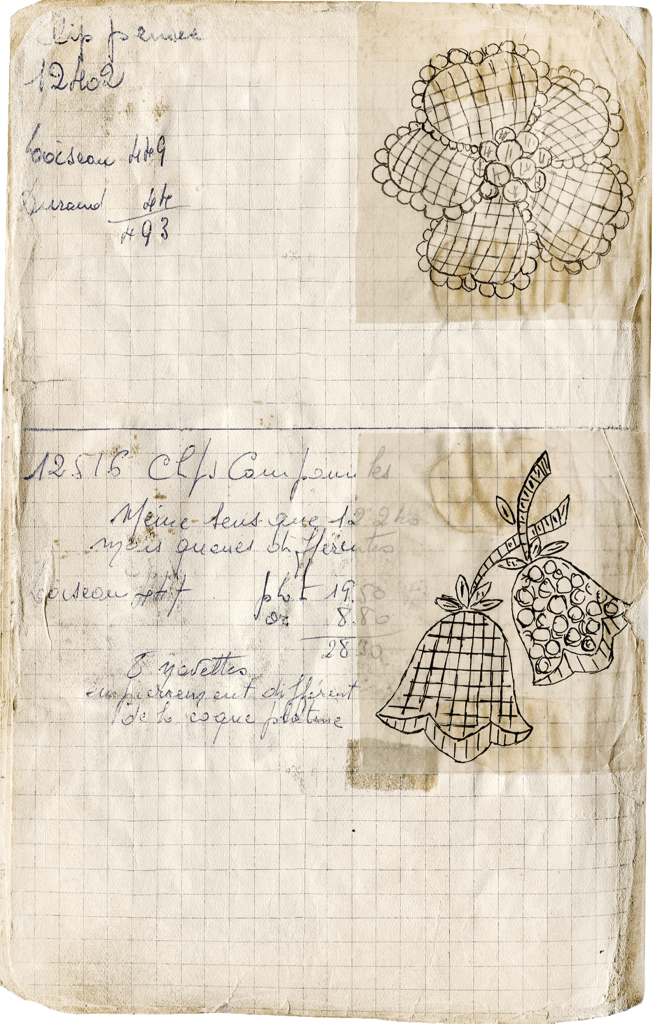

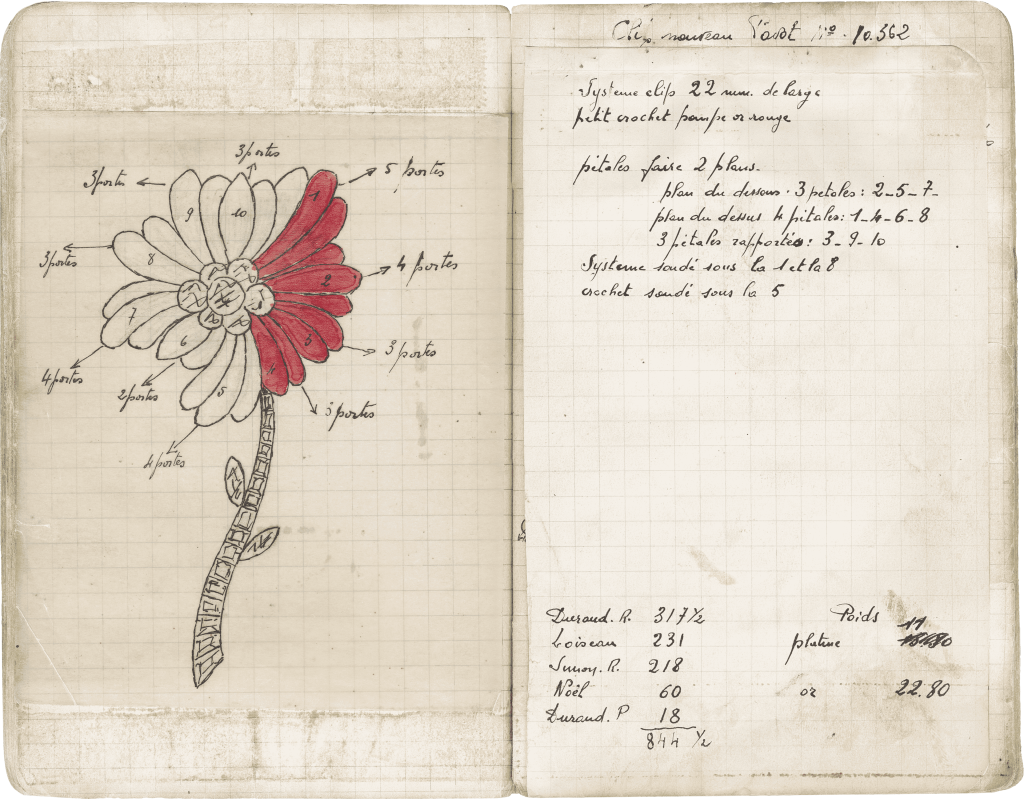

The technical excellence of the jeweler and the lapidary

Many years of experience are required for jewelers and lapidaries alike to master the demands of the mystery set technique and attain the very highest degree of excellence. When a piece of jewelry is being made, both jeweler and lapidary must interact with each other. Based on the chosen motif, the jeweler makes a flat drawing of the stones in a notebook and determines the number of doors. These are located in the widest parts of the piece to supply all the surfaces with stones.

The jeweler, part architect part engineer, has to have three-dimensional vision, to anticipate the dilation of the metal for cutting the rails and shaping the “soul” of the piece. The role of lapidaries is “to dress the jewel”15Account given by the Van Cleef & Arpels workshops. and “illuminate the gems.”16Account given by the Van Cleef & Arpels workshops. They work on the piece directly, cutting each stone to order, creating the facets and notches. For that, they select the finest gems from the available batch. The mystery set lapidary expert has an “eye for capturing the beauty of color.”17Account given by the Van Cleef & Arpels workshops. In fact, the cut brings out the depth of nuances as if the lapidary “were capturing the color of the stones.”18Account given by the Van Cleef & Arpels workshops. The absence of metal gives the piece a totally different perception to when the mount is visible. The mystery set enables gemstones “to send colors to each other” and “to live among them”. The experts in the Maison’s Stone Department say “that they warm each other.”19Account given by the Stone Department at Van Cleef & Arpels.

A technique that has become emblematic

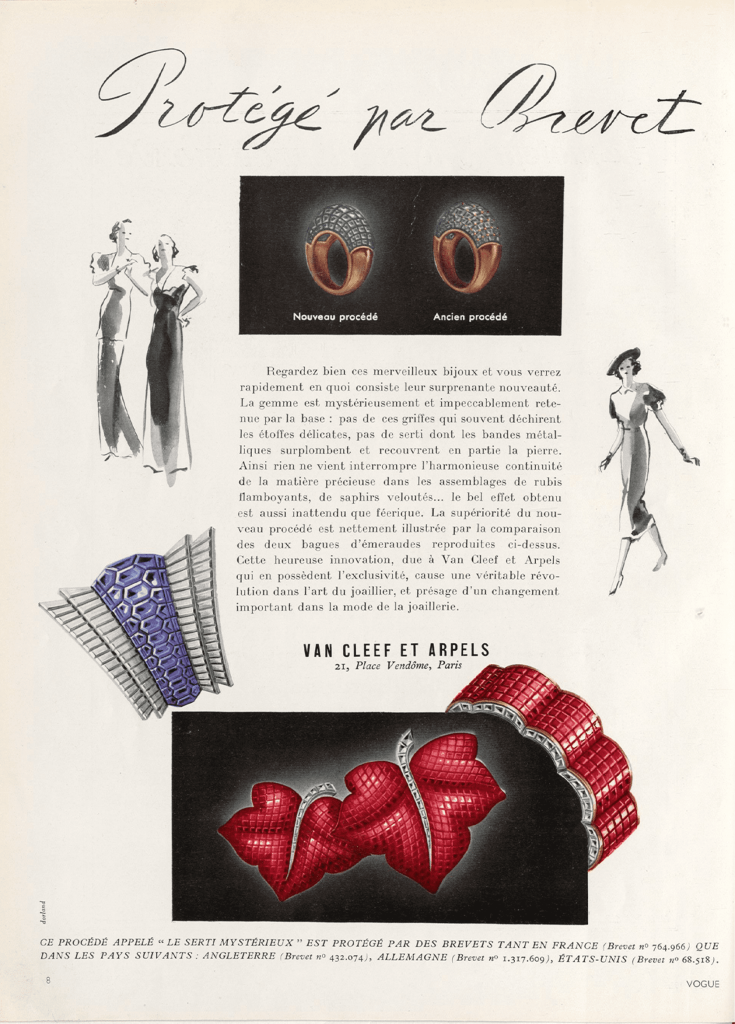

The mystery set contributed to the validation of the style, excellence, and renown of Van Cleef & Arpels. The Maison accompanied the artistic development of mystery set jewelry, promoting its novel technique and claiming authorship of it through advertisements. The July 1936 issue of Vogue Paris, for instance, dedicates a full page with the title “Protected by Patent” to this innovation. The article states: “Look at this marvelous jewelry carefully and you will soon see what constitutes its surprising novelty. The gem is mysteriously and impeccably held by the base; there are no claws that so often snag delicate fabrics, no mount with metallic bands overlapping and partially covering the stone. Nothing interrupts the harmonious continuity of the precious material in clusters of flamboyant rubies or velvety sapphires. The resulting effect is beautiful, as unexpected as it is enchanting. […] This fortuitous innovation, created by Van Cleef and Arpels who own the exclusive rights to it, is causing a revolution within the jewelry arts, and presaging an important change in jewelry fashion.”20Vogue Paris (July 1936): .8

The mystery set also came to be associated visually with the name Van Cleef & Arpels, becoming an emblem for it. The design of an advertisement dating from 192921La Renaissance de l’art français et des industries du luxe (December 1929): n.p. showing two motifs frequently used in the Maison’s corporate identity, the Vendôme Column and the facade of the Ségur and Boffrand private mansions forming one side of Place Vendôme, was reused in 1932.22La Revue de Paris (December 15, 1932): 5. This was just a few months after the partnership between Van Cleef & Arpels and Atelier Langlois was established, and a year before the registration of the first patent. In the second advertisement, the column is still shown in silhouette, but the facades now resemble gemstones.

From success to abandonment, from abandonment to renewed interest

Every single mystery set piece has contributed to the Maison’s artistic and technical path to excellence, from the early, flat-surfaced objects made in 1932 to the curved forms of the Creole rings, the first to use volume, as well as pieces available in a range of variations, and even one-off creations. In just five years, Van Cleef & Arpels succeeded in mastering and glorifying the mystery set technique, anchoring it as one of the foundations of the Maison’s distinctive style. The 1937 Exposition internationale des arts et des techniques appliqués à la vie moderne held in Paris represented the height of the mystery set creations of the 1930s. The Chrysanthemum clip and Peony double clip were exhibited at this event, helping to gain recognition for Maison Van Cleef & Arpels.

Peony clip

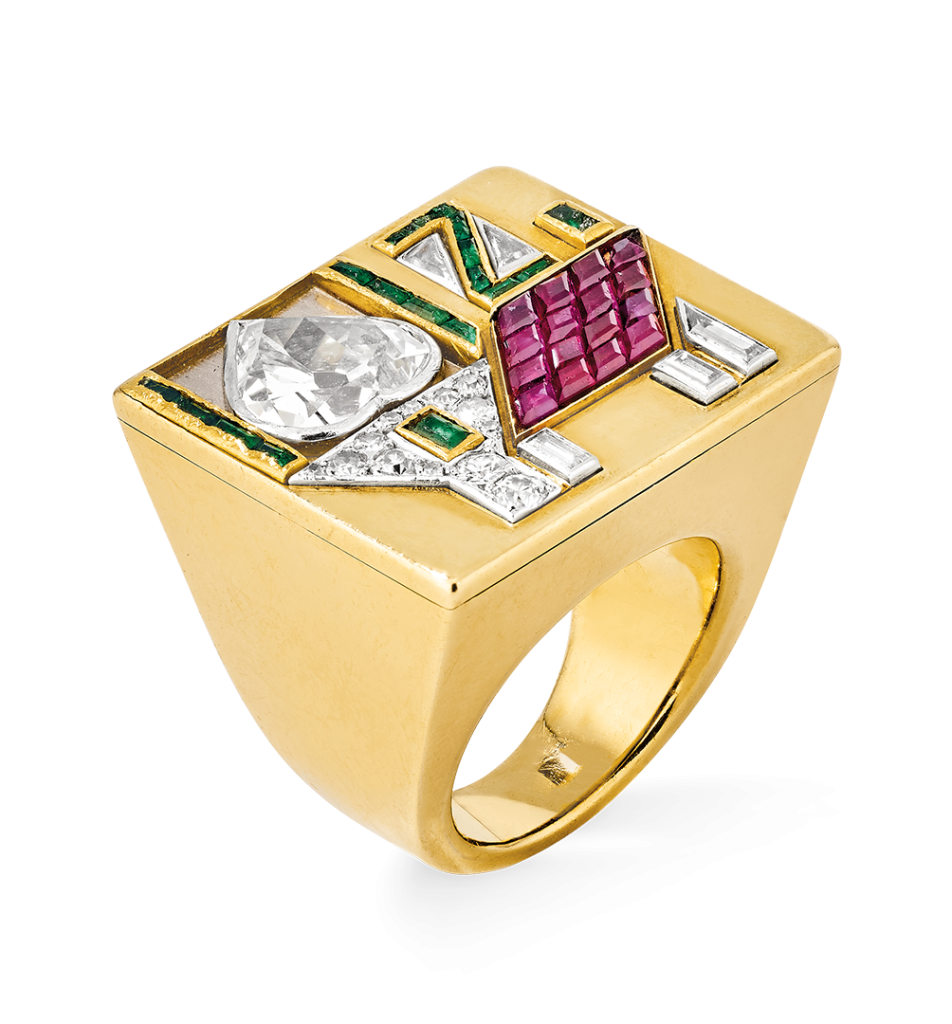

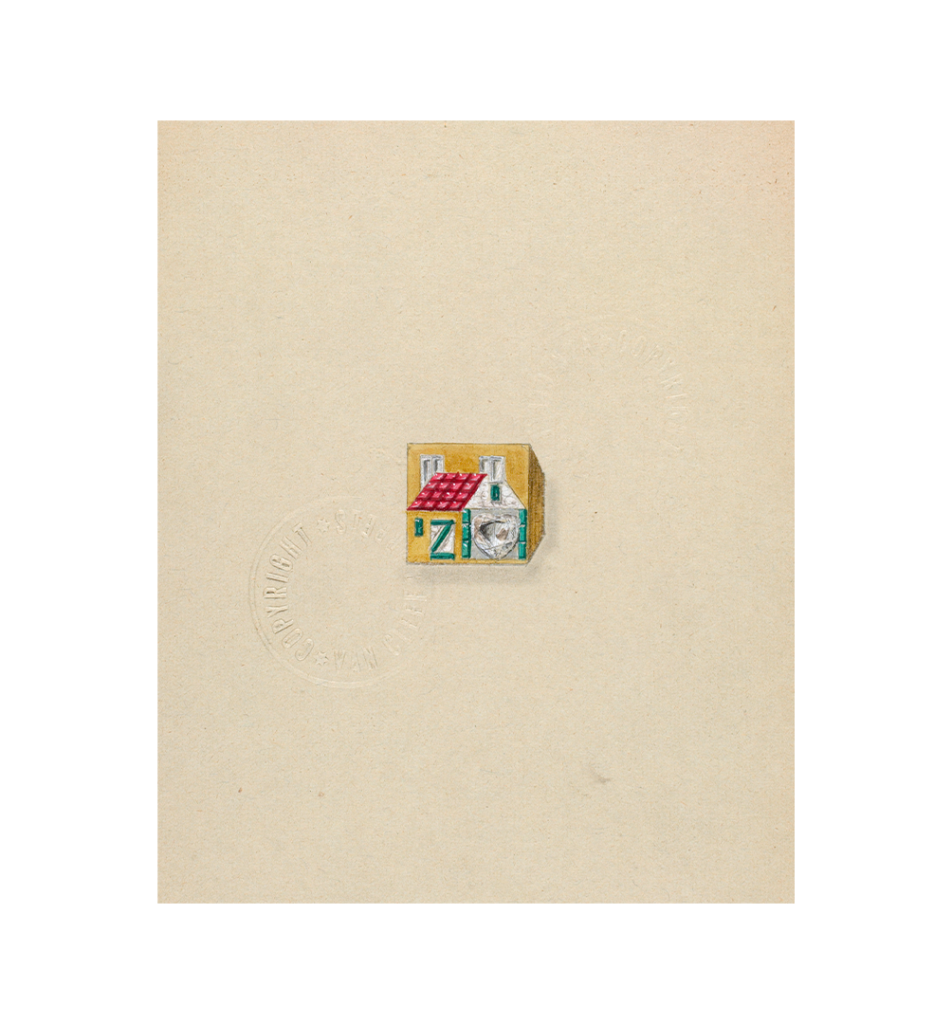

Despite this success, the mystery set technique was all but abandoned in the 1940s. The Cottage ring, from 1942, was one of the rare exceptions. The Second World War, the difficulty of finding experienced jewelers and lapidaries, the demands of long apprenticeships, and the time and cost of such a technique were all factors that endangered its very existence within the Maison’s creations. It took all the willpower and tenacity of the Arpels brothers to orchestrate its comeback in the 1950s, including calling upon a retired lapidary living in the south of France to train a new generation of gem-cutters.23Correspondence. Paris, Van Cleef & Arpels Archives.

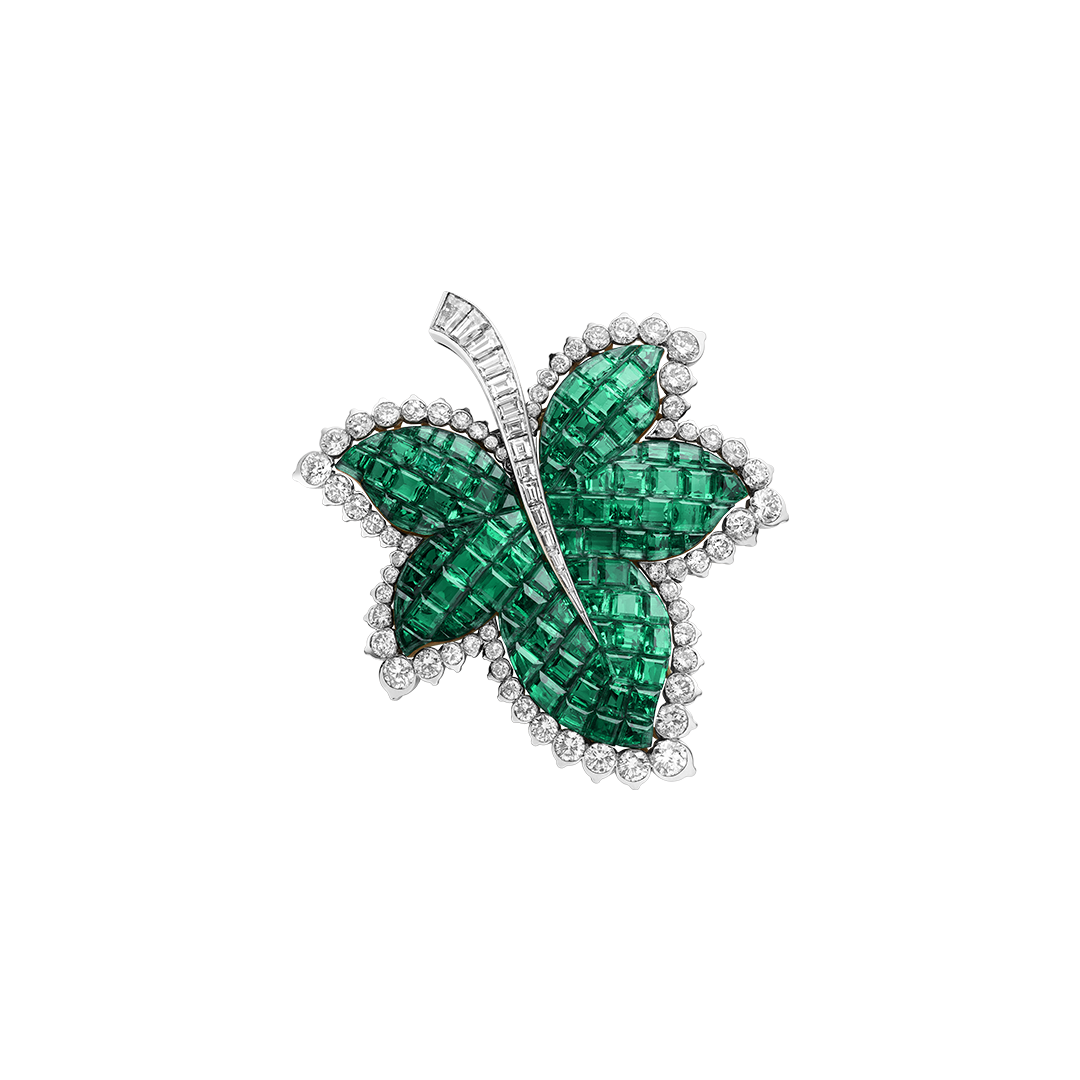

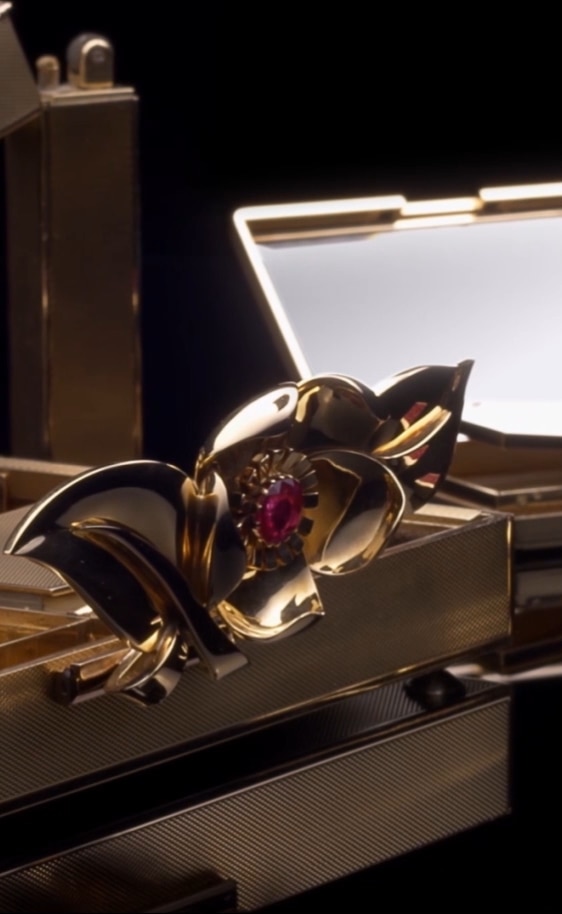

Some of the emblematic models from the 1930s were reproduced, like the Boule ring, the Wave bracelet, and the cufflinks. The 1950s also saw the appearance of original models inspired by nature, such as a range of clips, including Poppy, Plane Tree Leaf, and Vine Leaf. These pieces boosted the creative revival of mystery set jewelry with variations that heralded the signature collections of the following decades.