Mélodie Le Lay

Unparalleled, sumptuous, heavy brocades, duchesse satins with vivid reflections, aglow with diamonds and precious stones, impressive both in quantity and in quality. Desires… unobtainable dreams for most people follies that our couturiers nonetheless presumed to create with intense pleasure, but also as a devilish temptation for those for whom this regal finery was not an impossible pipe dream.”1Anonymous, “Ors et diamants sur les tissus,” L’Art et la mode, no. 2712 (1946): 35.

This article, modestly titled “Gold and Diamonds on Fabrics,” dating from 1946, evoked this relationship that exists between jewelry and clothing—one as lavish and intimate2Our use of this word here refers to a link deeply rooted in time, something tactile, almost carnal, relating to the mutual emulation and blossoming of these objects by being worn together. as it is ancient. It was illustrated by three silhouettes wearing creations by couturiers and jewelers. Dresses by Bruyère and Balmain were adorned with necklaces respectively designed by Mauboussin and Mellerio (known as Meller). The third silhouette wore a top in the shape of a bow, designed by Jacques Fath, dotted with a flight of Bird and Bow brooches, most probably in diamonds, created by Van Cleef & Arpels. This group of brooches, delicately pinned to the fabric, highlights the woman’s décolleté in a play of contrasts, as well as the lines of the garment itself.

An association since the 16th century

How innovative was this? Despite this proposal being in sharp contrast to the period, we are essentially talking about tradition here. Van Cleef & Arpels was pursuing an ancient approach first used by goldsmiths and then by jewelers. While the earliest pieces of jewelry that have come down to us date from at least 5000 BCE, this association between costume fabric and jewelry has been particularly evident since the sixteenth century. Jooris van der Straaten’s 1573 portrait of Elisabeth of Austria—who as the wife of Charles IX, King of France, made a lasting impression despite her short reign as queen from 1570 to 1574—tells us something about this marriage between jewelry and costume.

The young queen’s outfit was typical of the third quarter of the sixteenth century, dotted with jewels, some with a practical purpose in addition to an esthetic one, others highlighting the lines of the female figure. Some of the jewelry worn by the queen was also typical of the sixteenth century: a carcanet,3The carcanet was a typically Renaissance jeweled collar or necklace worn closely fitted to the base of neck that could be divided into bracelets. a côtiere,4The côtière, worn from the Middle Ages through to the seventeenth century, was originally braid or lace used for decorating the neckline of a bodice. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, it was created as a piece of jewelry and adorned with a pendant. and a demi-ceint.5The demi-ceint or half-girdle was the principal form of belt used from the seventh to the seventeenth centuries, combining fabric and chain. It was enlivened by sumptuous stones and pearls, becoming a piece of jewelry worn by female members of royal households from the late fourteenth century onwards. These three items alone reveal the strong link between clothing and jewelry, but it is the gemstones, set and stitched to the sleeves and wimple, that make this link all the more evident. They form a bejeweled resilla design on the bodice, concealing the stitching and offsetting the slashed sleeves, a costly decorative technique in clothing.

This association of jewelry and clothing was to continue through to the twentieth century and assumed many different forms. Two aspects seemed to be central to them all however: mutual imitation, if not emulation, between jewelry and clothing,6In this text, we shall only look at the imitation of clothing by jewelry. and the evolution of both favoring the creation of a “vestimentary ensemble,” a notion we will define further on.

Limitless inventiveness

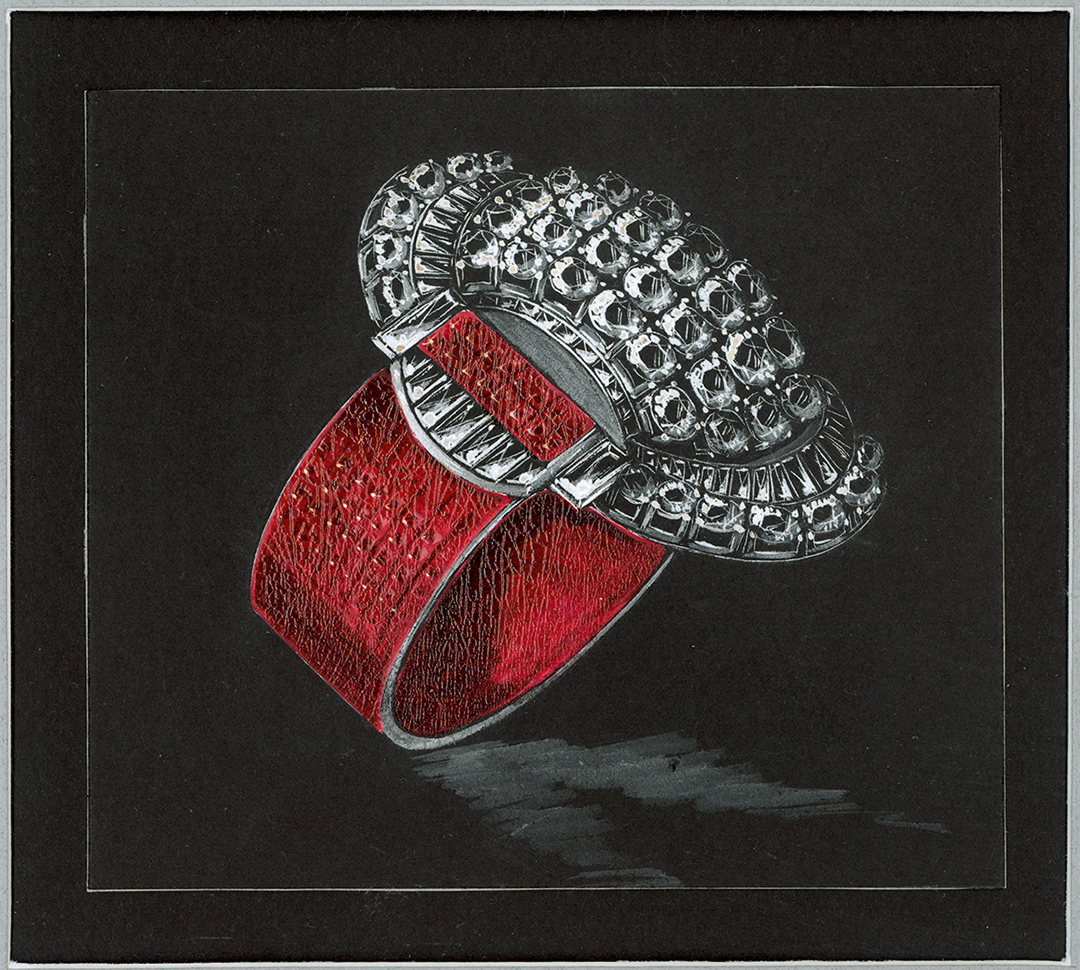

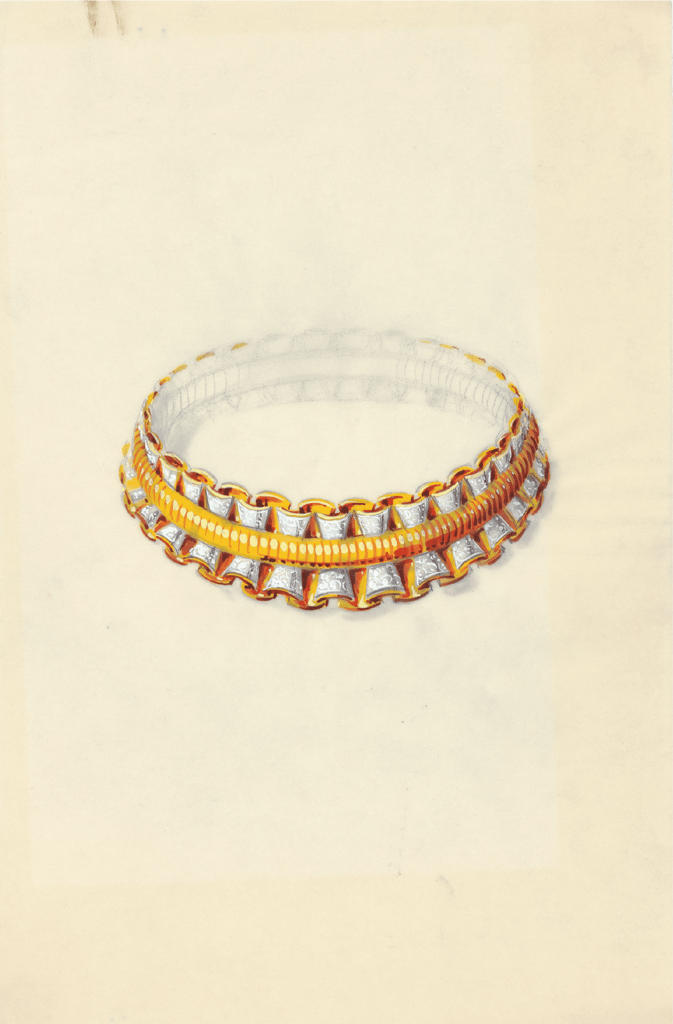

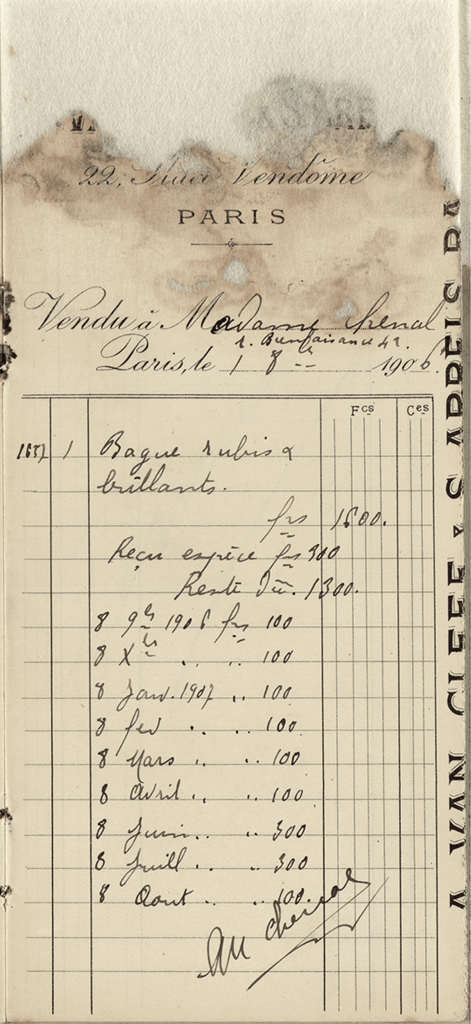

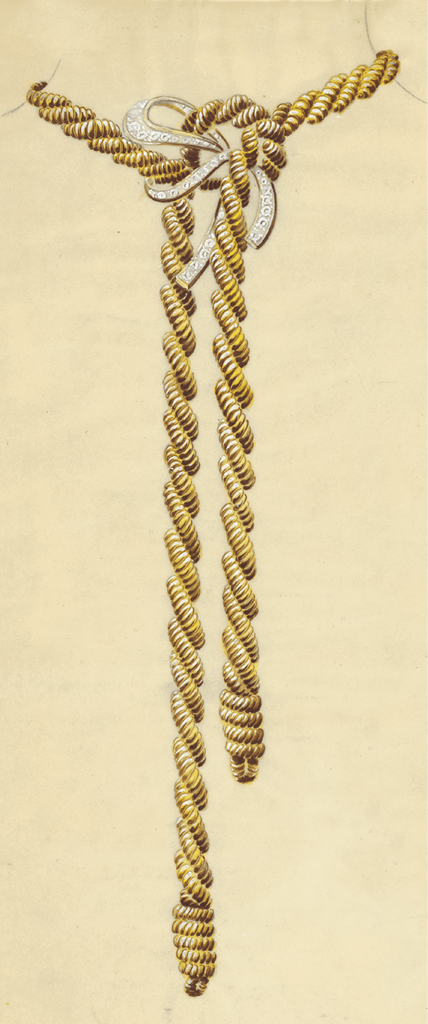

From its foundation in 1906, Van Cleef & Arpels adhered to this traditional jewelry repertory that drew its motifs from the clothing. During the first half of the twentieth century, the Maison’s founders and their descendants were immensely creative with the inspiration they sought from clothing and textiles. Bows and a variety of ribbons were omnipresent in its production, but the inventiveness of the Van Cleef and Arpels families did not stop there. We may refer here to the Handkerchief clips, the Fourragère clip, the tie-necklace, the Jarretière bracelet, the Zip necklaces, the Jersey and Serge fabric motifs, and other imitations of lace and netting, to mention just a few. Without forgetting the Ludo bracelets, inspired by belts.

References to ancient costume

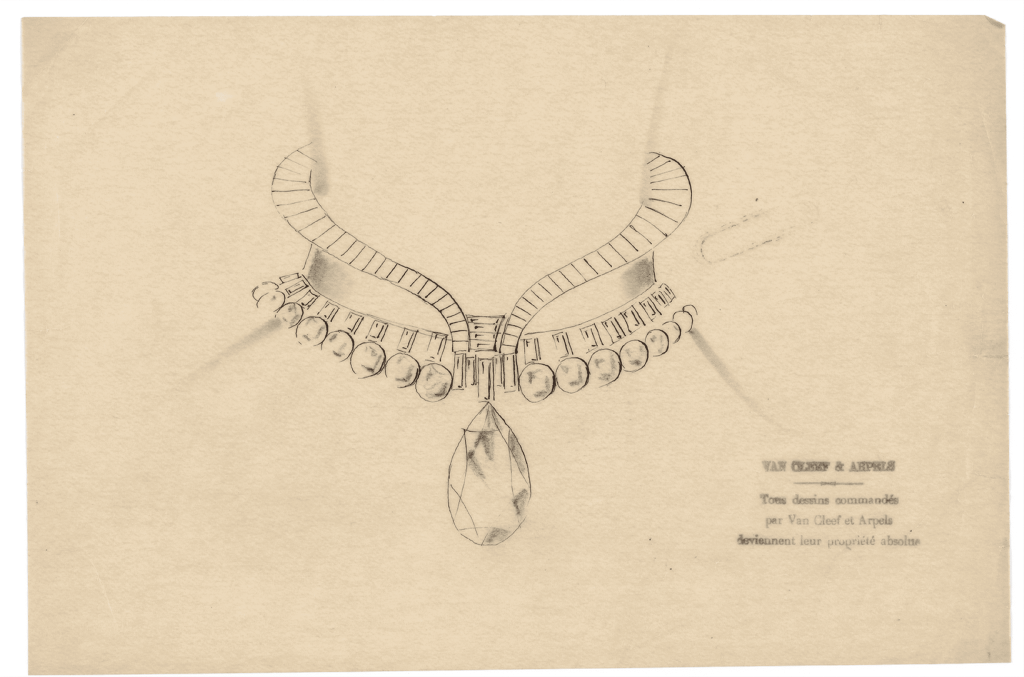

One of the most surprising examples is seen in the Medici necklace made in 1937, which was inspired by the delicately ruched collars of the sixteenth century, as we can see in a portrait of Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots, at age twelve or thirteen7The portrait referred to here is a pencil and watercolor drawing dated circa 1555-1559 and housed in the Lubomirski Museum at the Ossolineum in Poland. It is part of a series by François Clouet of the children of Henri II and Catherine de Médicis, Marie Stuart having been briefly married to François II, who died very young. The portrait’s gold embroidery, and gold-plated jewels reveal the close relationship between jewelry and clothing. where the ruching of the blouse billows over the top of a collar dotted with beads and underlined by a carcanet.

The Medici necklace echoes this composition closely, but with different materials: linen for Mary Stuart’s collar, diamonds for the Maison’s necklace. The carcanet is also lined with a row of round diamonds, while a pear-shaped diamond in the center rivals the luxury of the young queen’s dress. Collars in general were an abundant source of inspiration for the Maison, which, over the years, successfully adapted them to the taste of the day.

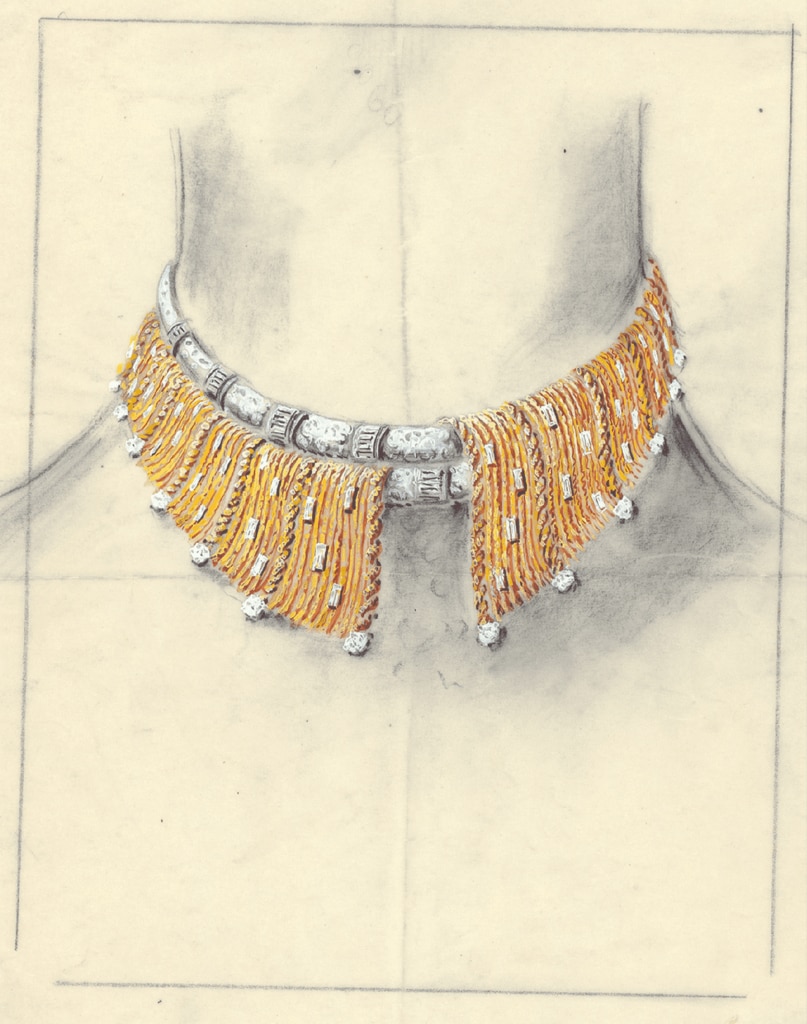

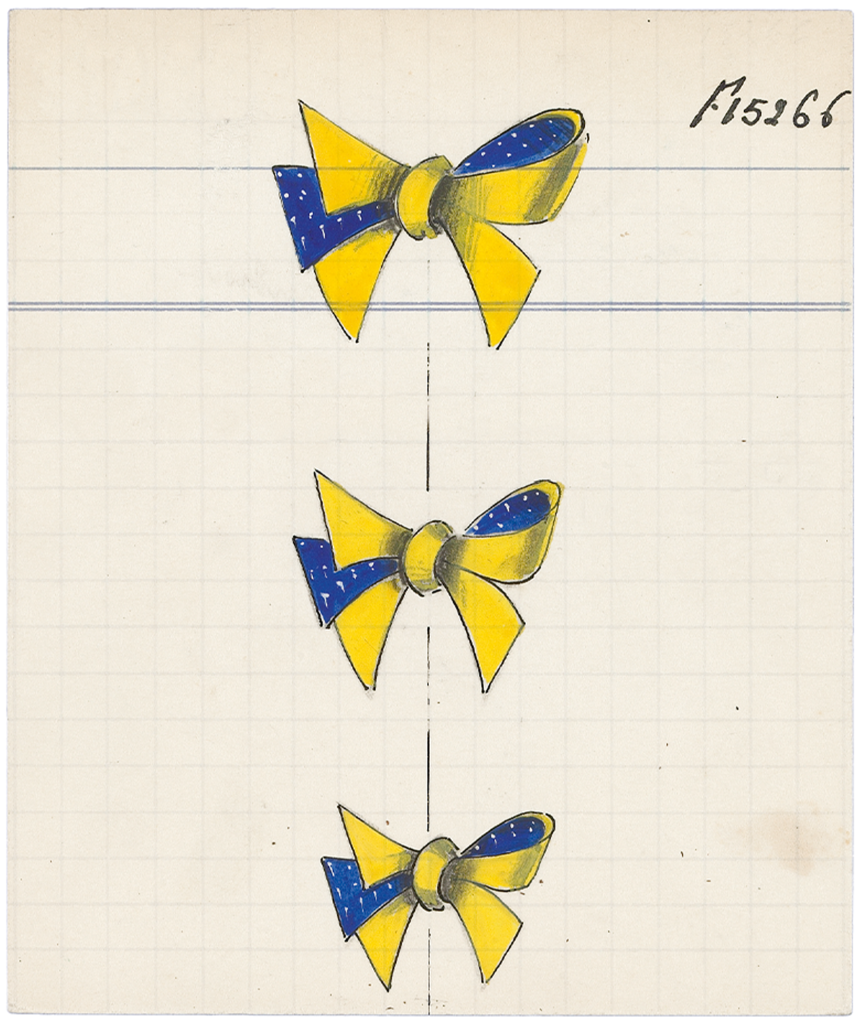

References to costumes of the past were equally successfully adapted and were part of a broader trend from the late 1930s to the late 1950s. For example, Van Cleef & Arpels reinterpreted a decorative technique—multiple horizontal bands of ribbons—that typified women’s clothing in the eighteenth century. On the eve of the Second World War, the Maison looked to the Age of Enlightenment and the splendor of royal clothing. Around 1938, it devised sets of jewelry for adorning the bodices of dresses with three bows of different sizes in gold and precious stones. There were a lot fewer bows here than in the second quarter of the eighteenth century, but the effect was nonetheless maintained.

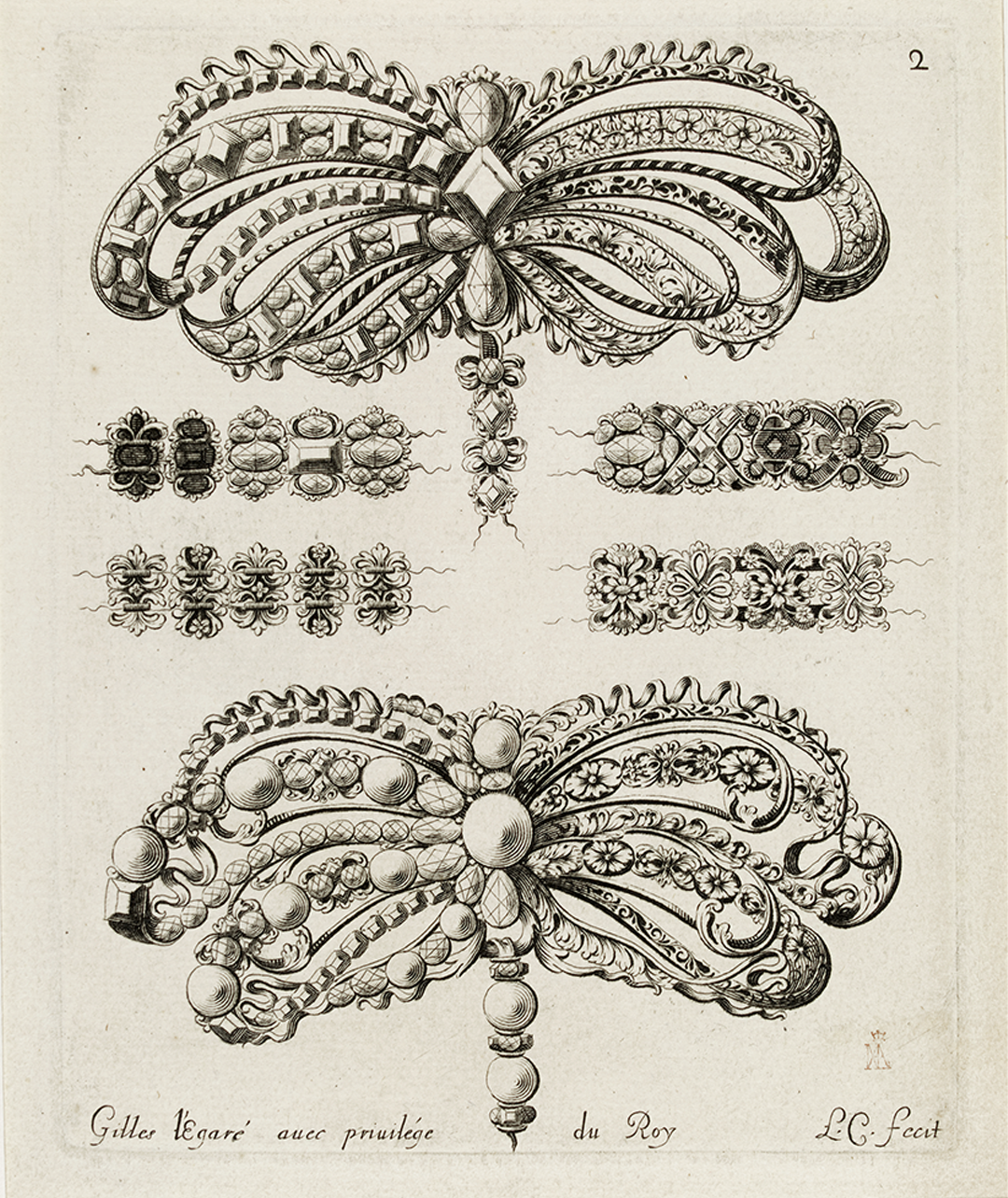

Bows as pioneer in the relationship between jewelry and clothing

Bows form a decorative language that featured very early on in the history of jewelry. Goldsmiths and ornamentists were brimming with ingenuity and creativity in their desire to transcend, albeit subconsciously, this link between jewelry and clothing. Among their number, Gilles Légaré (1617–1663)—goldsmith to the king—stood out and became a source of inspiration for posterity, in particular for his bow-shaped brooches known as “mislaid bows,” so called for being attached to the middle of a woman’s bodice. Jewelry was no longer used solely to enhance an outfit; it was also inspired by it and imitated it. This brightly shining bow, nestled among ribbons, frills, and other trimmings, glorified the garments of nobility, the likes of Madame de Sévigné, Marie-Antoinette in her coronation robes, or even the Empress Eugénie, a great admirer of the latter.

The use of noble materials

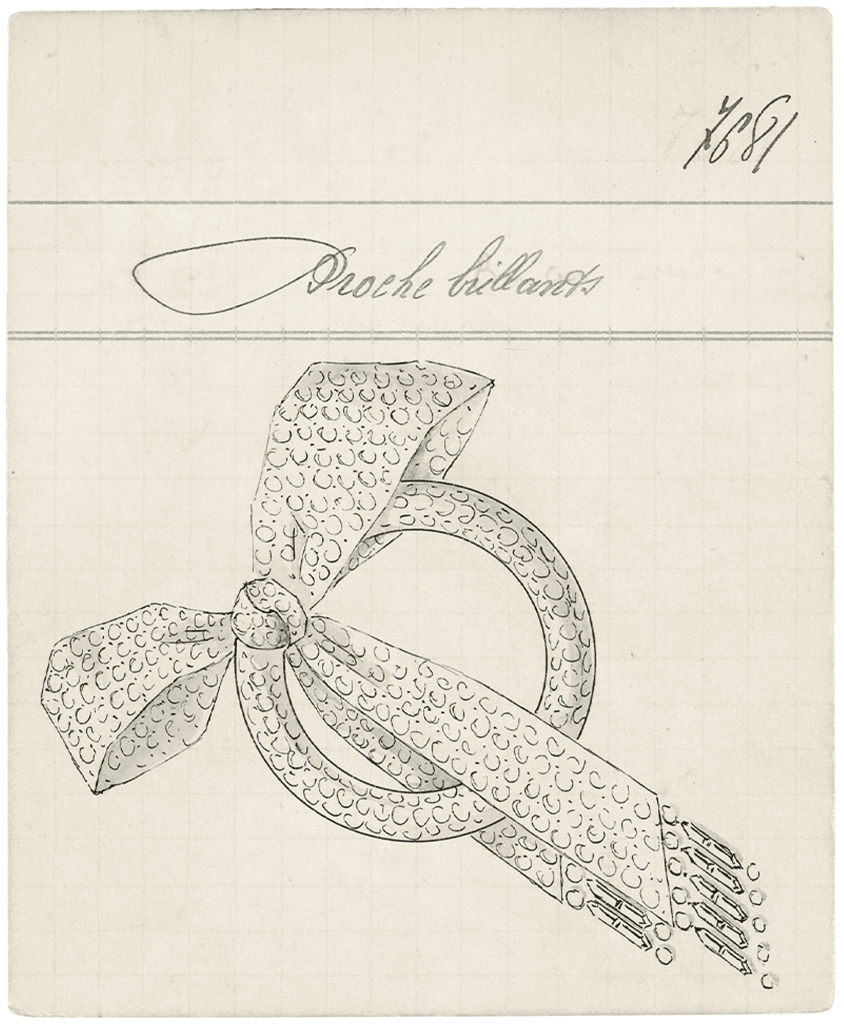

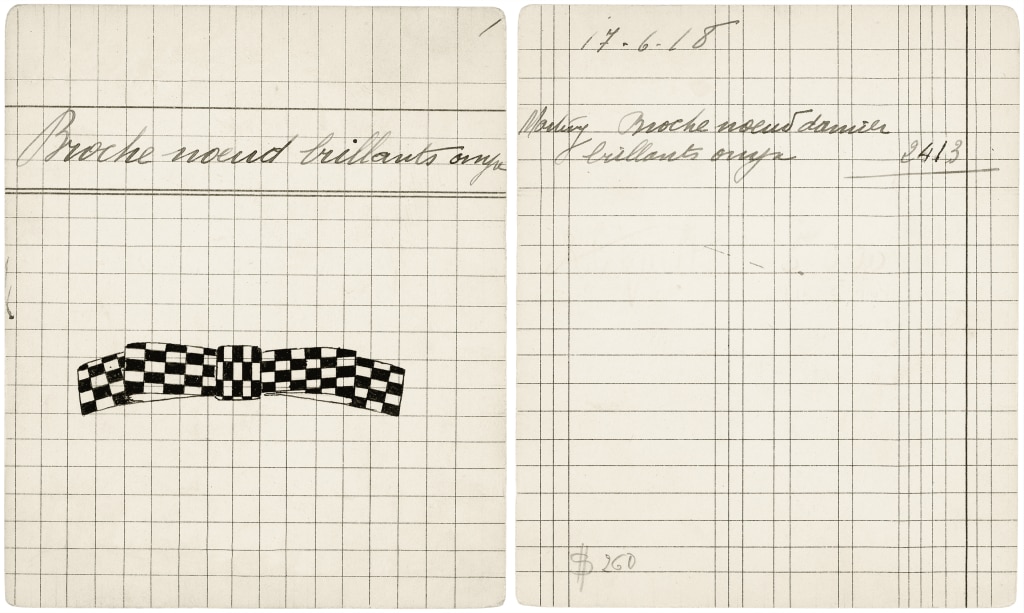

“Art and beauty [being] timeless,” Van Cleef & Arpels subscribed to this jewelry tradition that united clothing and jewelry with threads, or warps and wefts. This belief was expressed by the Maison in one of its advertisements in 1944 with an elegant woman pictured opposite Queen Marie-Antoinette as depicted by Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun in 1783. The woman wears a Bow bracelet around her wrist, reminiscent of those designed by Gilles Légaré in the seventeenth century. While bows were held in the highest esteem during the 1940s, the Maison had created pieces inspired by or transposing this motif with noble materials as early as 1906, as seen in a page from a ledger in the Maison’s archives noting a diamond Bow brooch dating from October 8, 1906.

In the 1920s, white diamond jewelry adopted the motif to adorn dresses and the lapels of women’s jackets. It was treated in a naturalistic manner, gently fluttering, imitating the flexibility of fabric ribbons, as seen in two brooches dating from 1928 and 1927. The fabric’s flexibility and flowing lines were further accentuated by the diamonds’ fire and the three-dimensional treatment of the piece.

The Art Deco movement, on the other hand, stylized the bow motif, playing on contrasts, and fluttering fabric gave way to straight lines. The use of contrasting colors, however, allowed for rhythm and movement, thus avoiding any sense of rigidity.

Imitating the suppleness of fabric

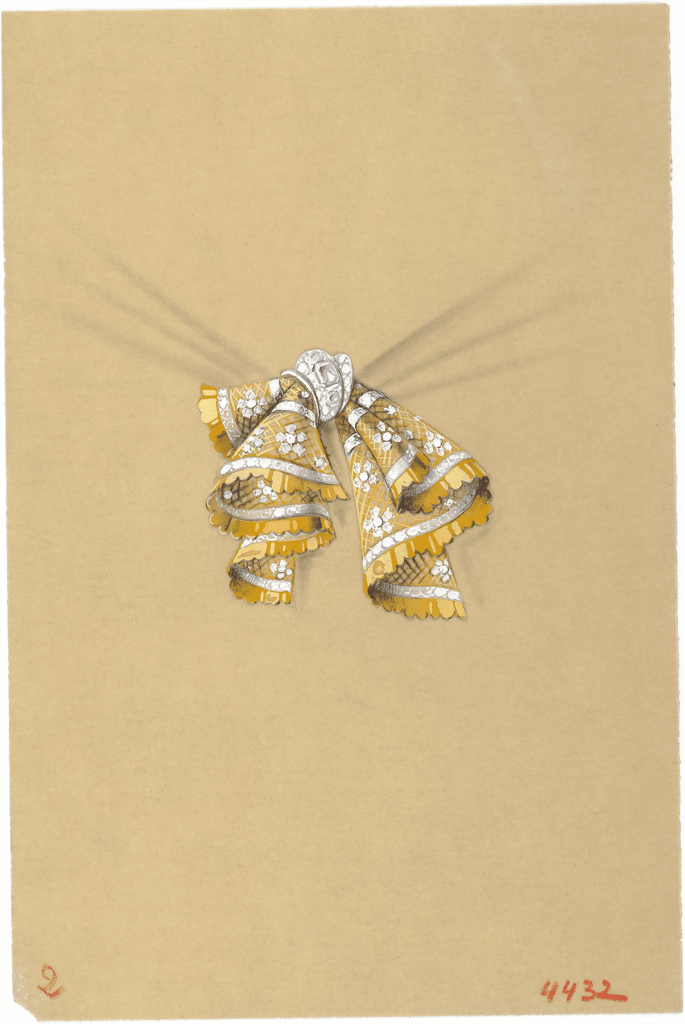

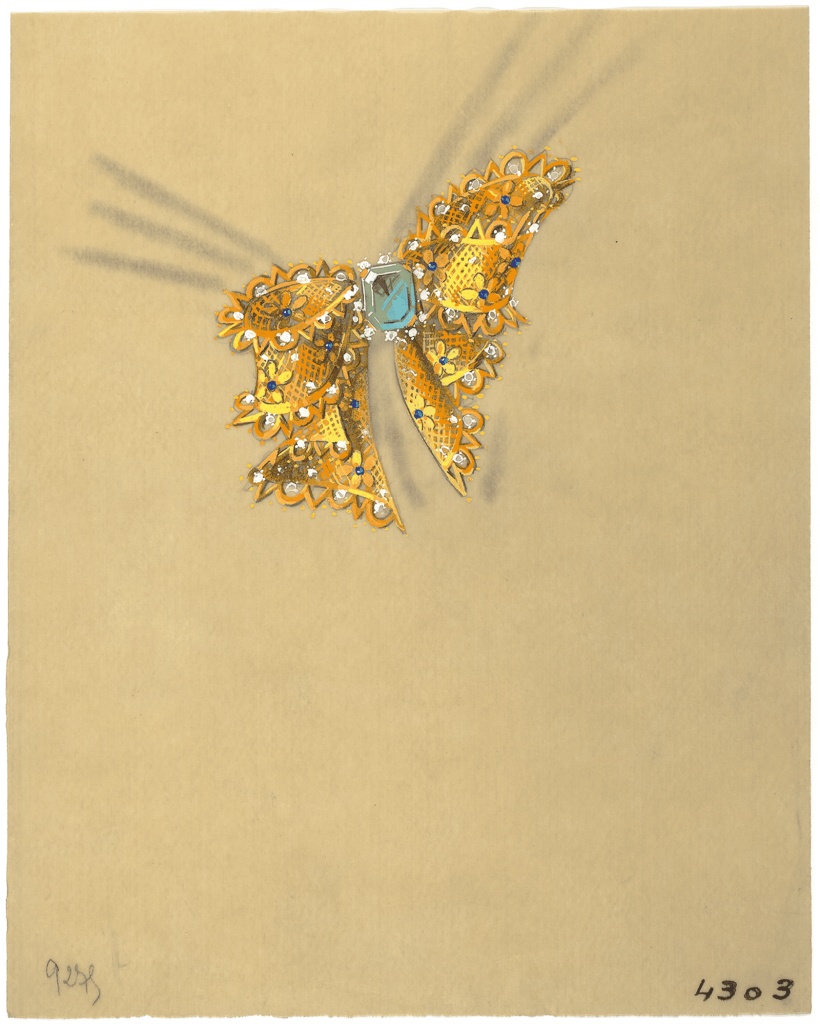

While bows were used in different types of jewelry, they really came into their own as brooches and clips, particularly in the 1940s when they were seen embellishing the female silhouette. The way in which they were imitated, however, changed; largely as a result of the fact that while the diamonds’ fire still played a part in these creations, it was gold that took pride of place. Access to raw materials, for both the arts and industry, was drastically limited by the war effort and the Occupation. “Intelligence and taste were not rationed,”8Mode du jour, no.1055 (February 5, 1942): 3. however, with regard to fashion, nor indeed for the jewelry houses. Gold was particularly used during this period, admittedly accompanied by diamonds, and this reflected the inventiveness and excellence of Van Cleef & Arpels’ work as a goldsmith. The pieces no longer simply imitated the waviness of a ribbon; they actually became its fabric, be it tulle, resilla, or lace.

The delicate gold lacework of a brooch dating from 1949, dotted with diamond flowers, illustrates how these jewelers managed to transcend the fabric by recreating its fluidity and flexibility in an immutable material. The Maison’s archives contain many drawings of these brooches lavishly imitating bows of fabric and ribbons.

The Serge and Jersey creations

Above and beyond the association of gold and diamonds, the use of different-colored metals, if not a few colored stones, gave rhythm to these compositions and life to these immutable fabrics. Stripes of red gold gave form to a ribbon while an aquamarine landed gracefully in the middle of a bow.

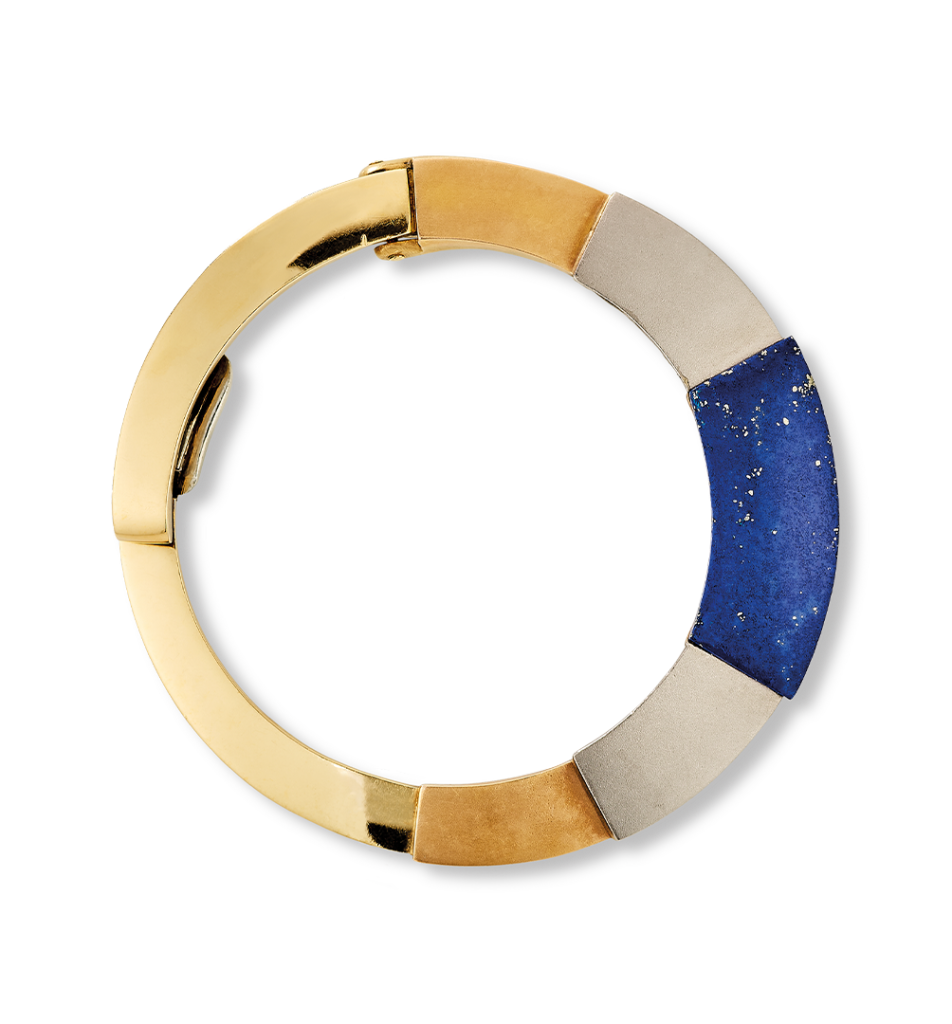

With its ribbons of diamonds, bows of gold lace, and fluttering handkerchiefs, the Maison took its imitation of textiles yet further, at the dawn of the 1950s, looking to contemporary fabrics for its Serge(8) and Jersey designs.

Warps and wefts were transformed into golden matter while retaining their flexibility. Golden fabrics may not have been new, but the materials that were imitated were increasingly prevalent in women’s wardrobes. Jersey, associated with Chanel since the 1910s, and jean twill were two textiles that symbolized practicality for women who, by the middle of the century, were leading increasingly active lives. Was this a coincidence? The orientation of these new looks put forward by Van Cleef & Arpels from the 1950s, seemed to prove otherwise.

The female silhouette in the 1940s

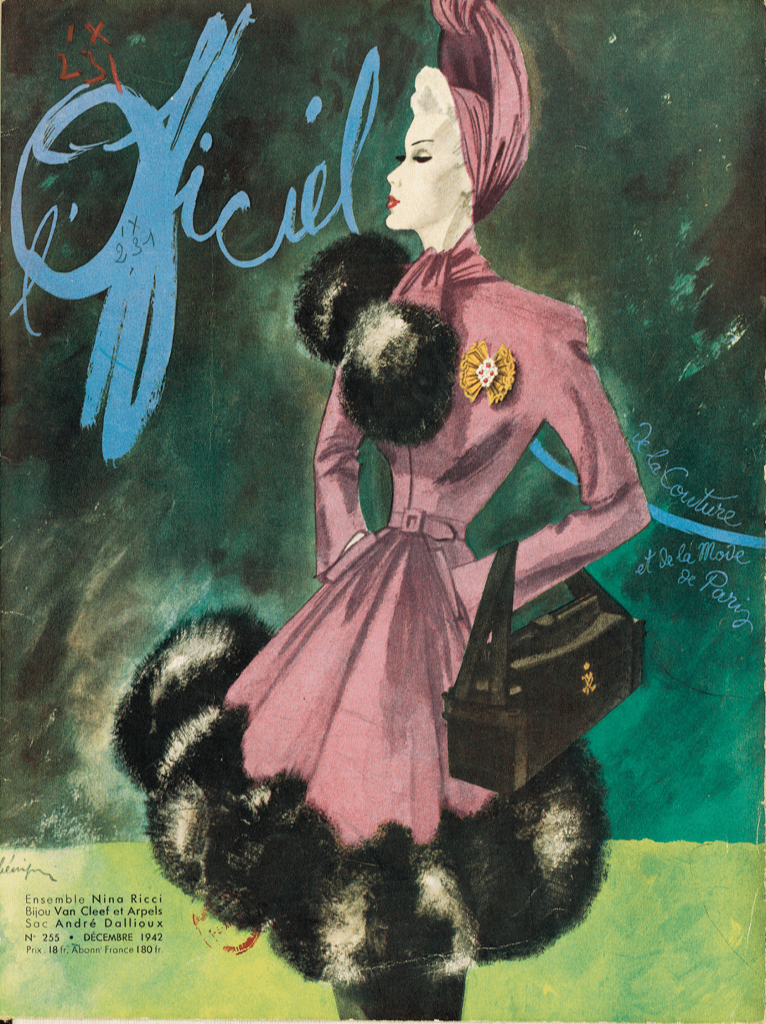

Furthermore, the angular profile of “women soldiers built like boxers”9Christian Dior, Dior by Dior: The Autobiography of Christian Dior (London: V&A Fashion Perspectives, 2018). contradicted the fluency of 1940s jewelry. The cover of the December 1942 issue of L’Officiel de la couture et de la mode de Paris illustrates this with a woman dressed in a straight coat with wide shoulders, fitted at the waist and hemmed with a strip of fur weighing down the lower half of the coat. A turban elongates the silhouette while a brooch composed of small diamond flowers positioned on a resilla bow softens this highly structured outfit. Jewelry played a vital role in the elaboration of the female silhouette, taking the edge off the contours of an angular look or structuring the line of a garment, as Elisabeth of Austria’s côtière had done a few centuries earlier.

“The vestimentary ensemble“

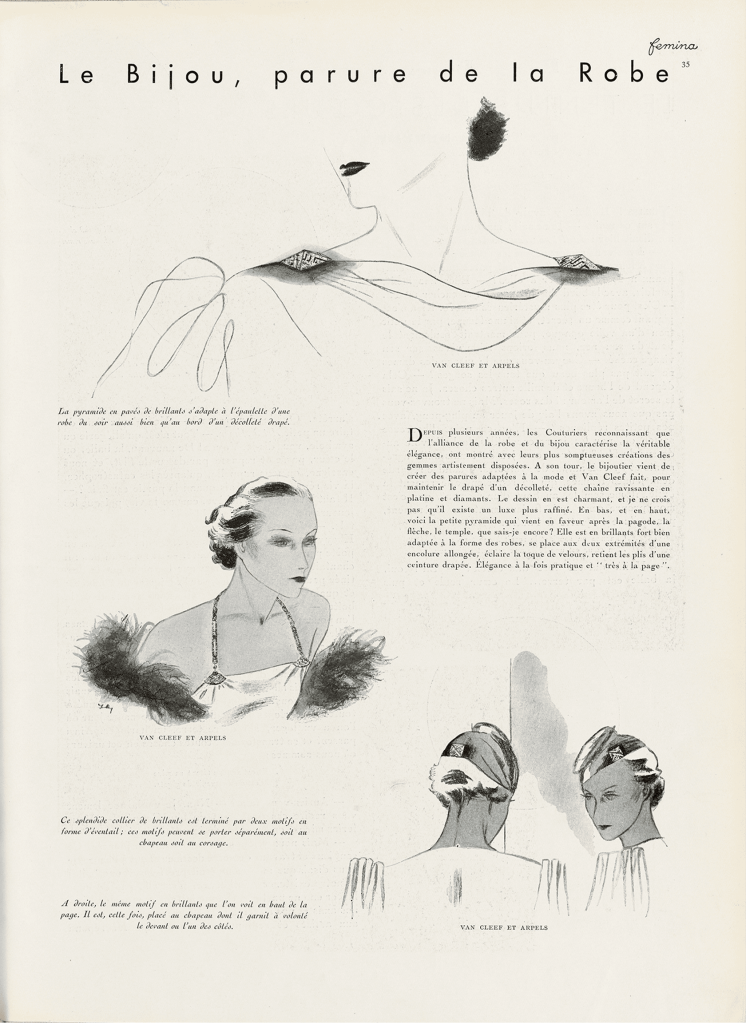

It is this contrast that enables this silhouette to illustrate the intimate link between jewelry and clothing. The richness of this link is expressed through the sense of belonging of both clothing and jewelry to what Roland Barthes calls the “vestimentary ensemble.” The latter does not refer to a gathering of disparate elements each with their own value, but rather to a system ruled by the standards of a given society, a group of individuals, at a particular moment and in a specified place. It is this ensemble—from undergarments to shoes via jewelry—that has to be analyzed if one wants to understand an era and more modestly, a silhouette.10See Roland Barthes, “Histoire et sociologie du vêtement [Quelques observations méthodologiques],” Annales. Économies, sociétés, civilisations, 12th year, no. 3 (1957): 430–441. To consider jewelry merely as a straight- forward element of male or female finery would be an oversimplification, for “it accords with the dress, hat, and hairstyle; it is the link between them in the form of a circle, a dot, a line that casts a favorable light on the ensemble.”11André de Fouquières, “Le bijou et la mode. Quelques pages extraites de Femina par Van Cleef & Arpels,” Femina (January 1933): 2. It is therefore designed in accordance with this ensemble rather than independently.

Van Cleef & Arpels follows the fashion train

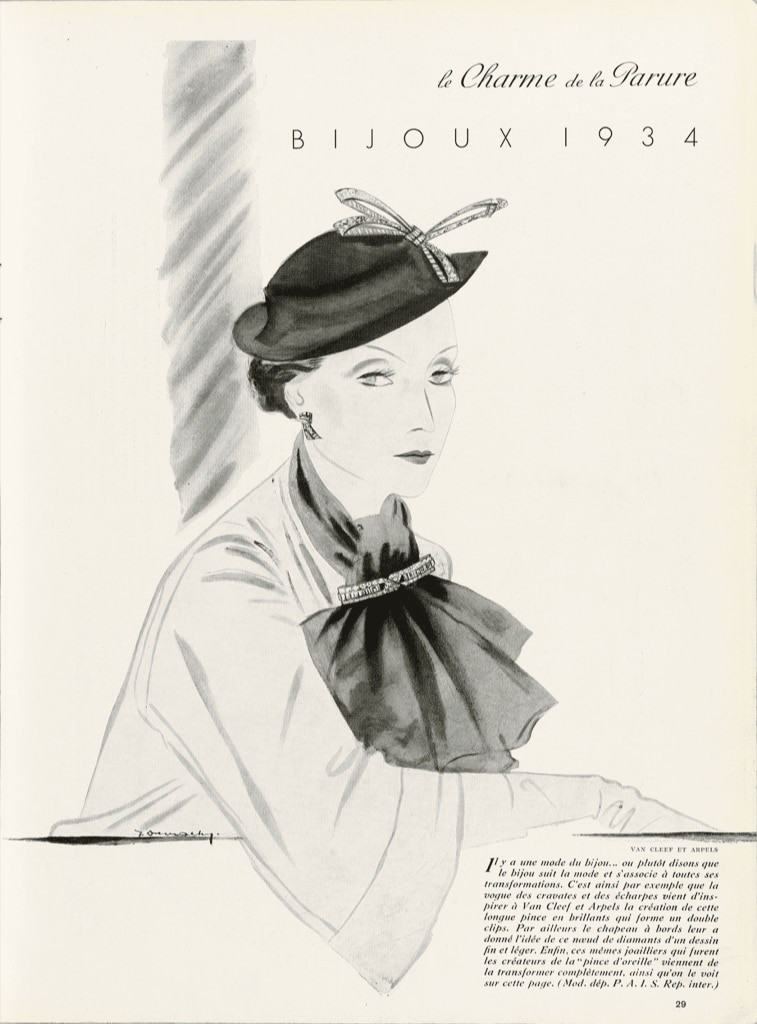

In 1934, an article in Femina magazine pointed out the Maison’s ingenious ability to follow fashion by creating jewelry adapted to its changes.12“There’s fashion in jewelry… or rather we should say that jewelry follows fashion and partners it in all its transformations,” extract from “Le Charme de la parure. Bijoux de 1934,” Femina (June 1934): 29. When scarves and cravats were in vogue, Van Cleef & Arpels came up with “a long clasp of diamonds forming a double clip”. The following month, the same magazine once again vouched for jewelry’s ingenuity in following the slightest variations in clothing and better adorning them, confirming that “every day it seems [to be] more intimately part of this fine and wonderfully observed ensemble that is a woman of taste’s grooming.”13Martine Rénier, “Le Charme de la parure. Bijoux de Paris,” Femina (July 1934): 37.

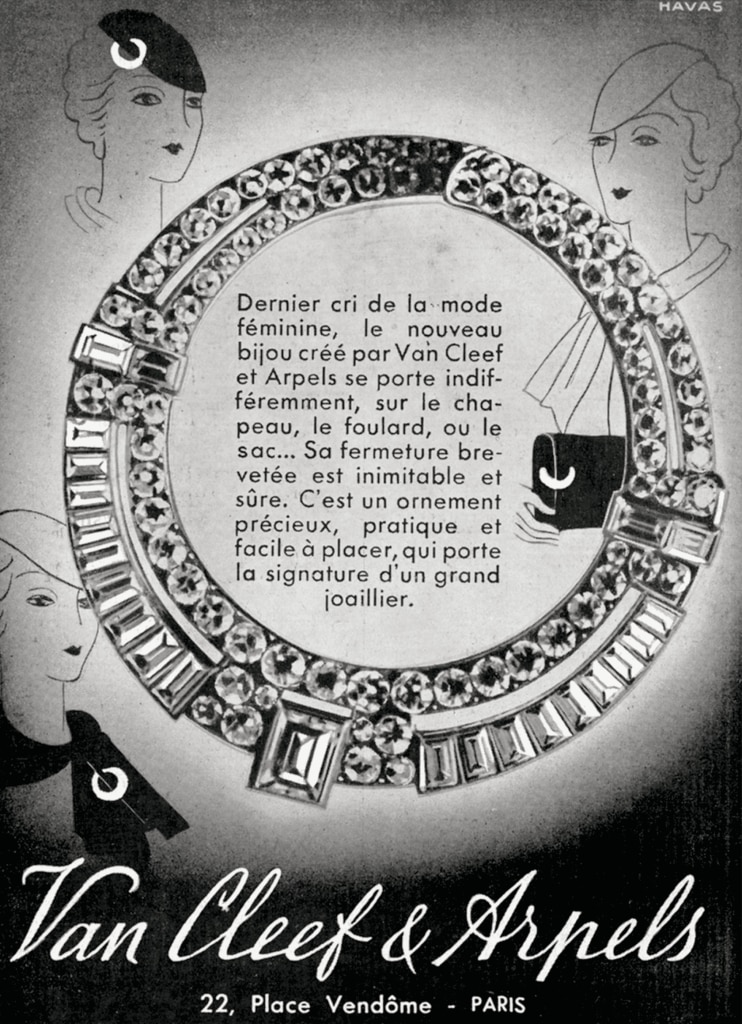

The Circle brooch—one of the Maison’s emblematic pieces during the 1930s—embodies this aptitude by adapting to different types of clothing suited to women with increasingly busy lives. It could be worn on a hat, knot a scarf, adorn a purse, or even be pinned to a jacket lapel.

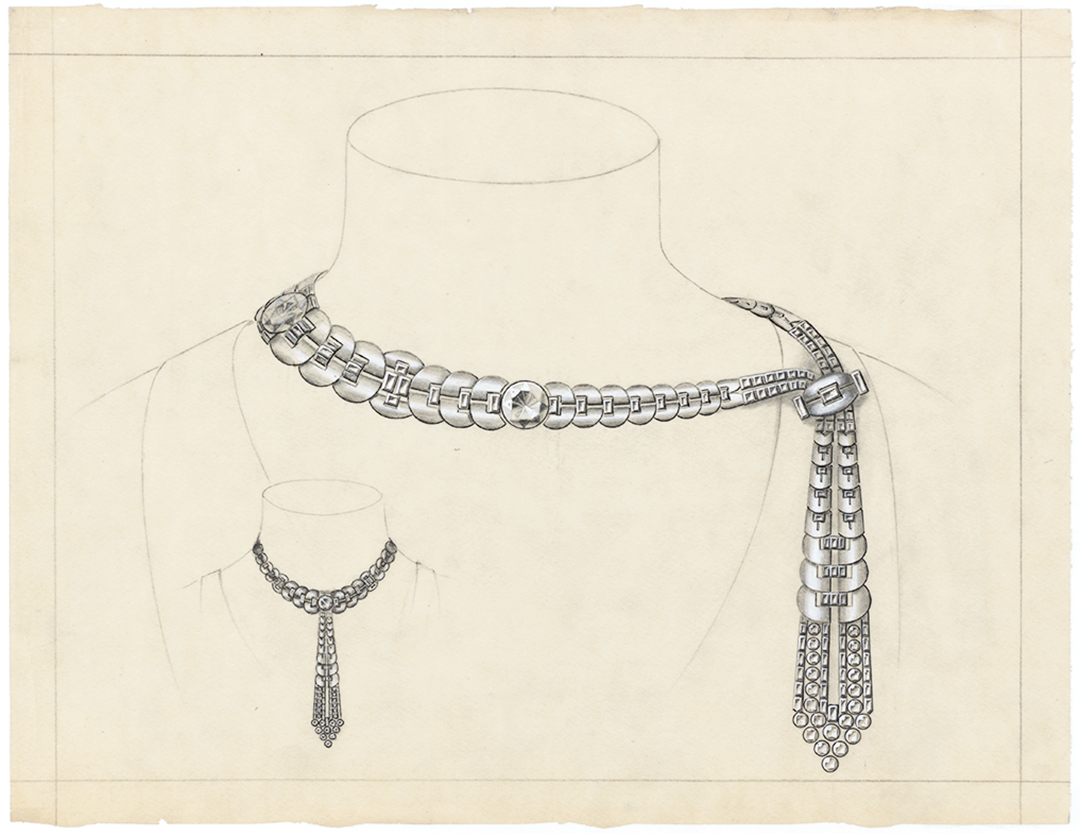

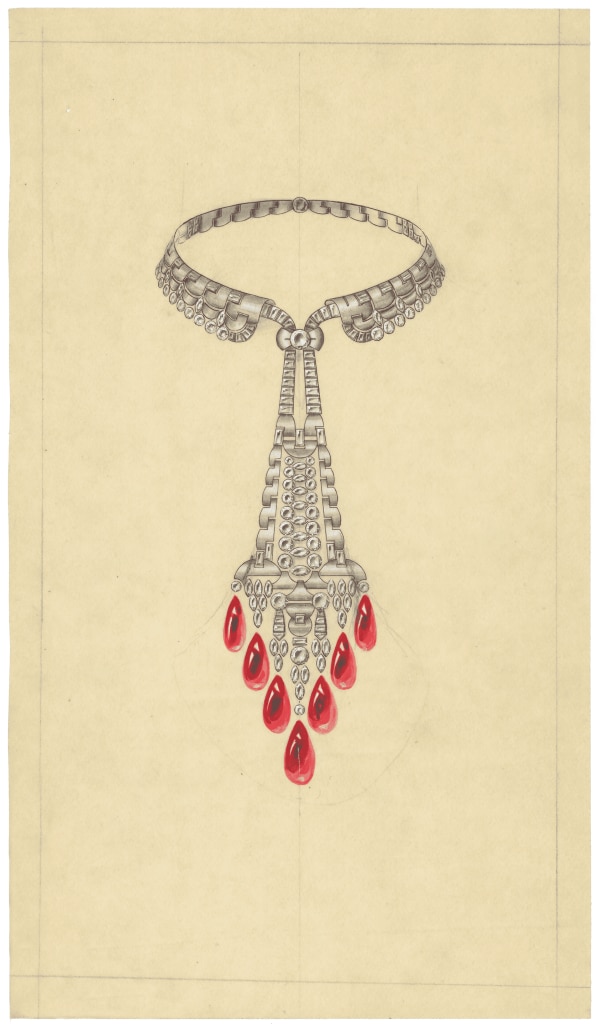

This model by Van Cleef & Arpels proved that jewelry belonged to this “vestimentary ensemble” as defined by Roland Barthes a few years later. It was part of this clothing-specific language in which the Maison’s jewelers were particularly well versed during the late 1920s. Tie-necklaces, as well as scarf-necklaces and even strap-necklaces, enhanced women’s necklines as much as the bodices of their dresses. More than mere jewelry, Van Cleef & Arpels’ pieces emphasized a woman’s silhouette at a time when this term was assuming a new meaning.

The female ideal according to Georges Vigarello

Clothing and the female body both followed the precepts of the Art Deco current. “A woman is her figure.”14Quotation from Vogue (1927) in Georges Vigarello, The Silhouette: From the Eighteenth Century to the Present Day (London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2016), 110. It was with these few words that Georges Vigarello summed up the feminine ideal that prevailed from the 1920s, in his book The Silhouette. The keywords for the female silhouette from that time were elongated effect, verticality, and straight lines. Georges Vigarello speaks of the “bodily form becom[ing] generally lighter and more supple, with narrower contours.”15Quotation from Vogue (1927) in Georges Vigarello, The Silhouette: From the Eighteenth Century to the Present Day (London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2016), 109. The lines of the female body also evoked those of Art Deco jewelry of the same period.

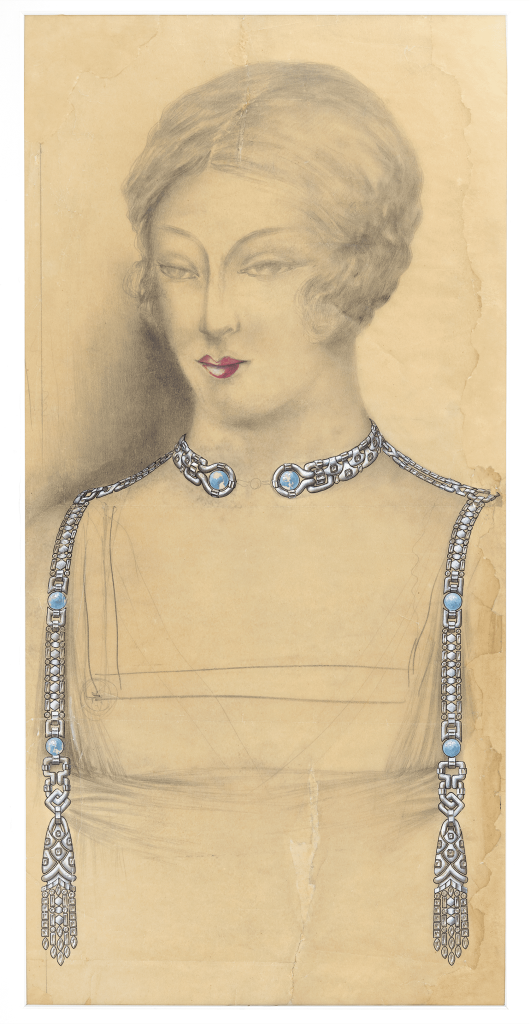

This new concept of the silhouette in the Roaring Twenties also called for jewelry for a woman’s wardrobe. The gouaché of the Belle de Jour necklace (circa 1927–1928) illustrates the importance of jewelry as a structural element of the female silhouette. This piece was composed of a very short necklace joined to two straps espousing those of the dress, all in diamonds and blue gemstones on platinum. The sparkling diamonds almost certainly echoed the embroidery on the dress.

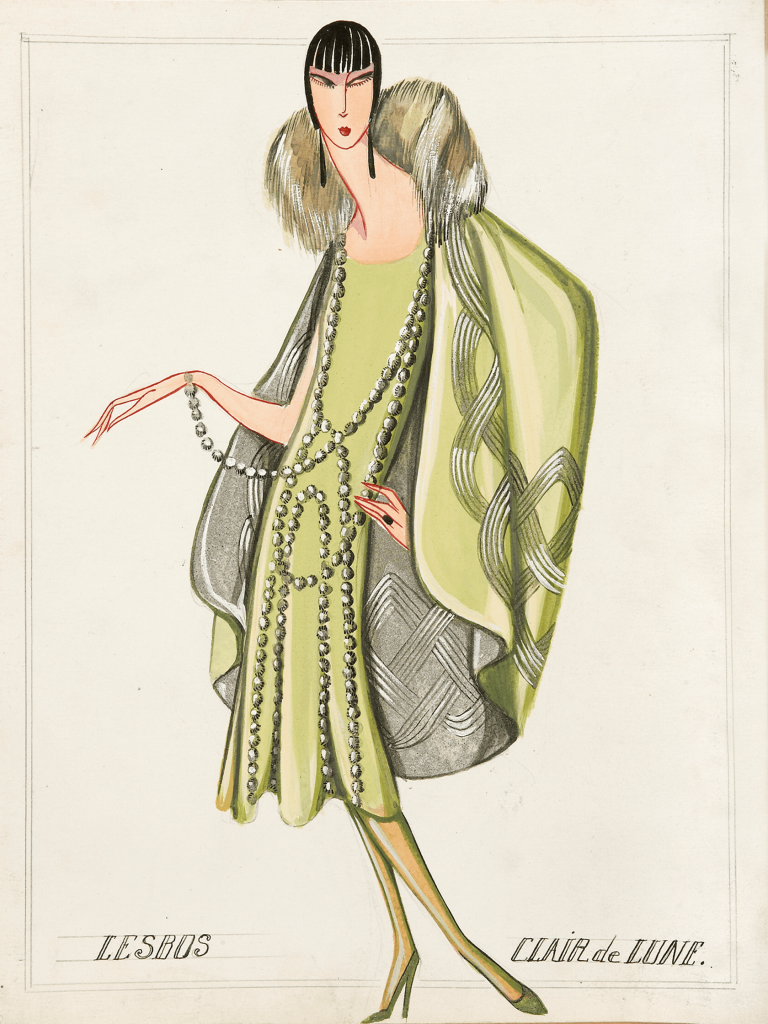

At this time, evening dresses were particularly embellished, notably with sparkling colored embroidery. Due to the weight of this kind of ornamentation, dress straps tended to be reinforced, as was the case for Jeanne Lanvin’s Lesbos dress made in 1925. The dress’ beaded and lamé decoration formed the main element underlining the verticality of the whole garment, in the same way as Van Cleef & Arpels’ Belle de Jour necklace. Maison Lanvin was playing here on the illusion of a long necklace, with jewelry and clothing joining forces to sketch the new silhouette that was in vogue at that time.

Van Cleef & Arpels returned to this idea of bejeweled straps in 1933 in the magazine Femina. Jewelry was no longer just finery but had become a functional element of the garment, here serving as a strap for a barebacked evening dress, a popular cut between 1930 and 1935.

The embroidery lexicon

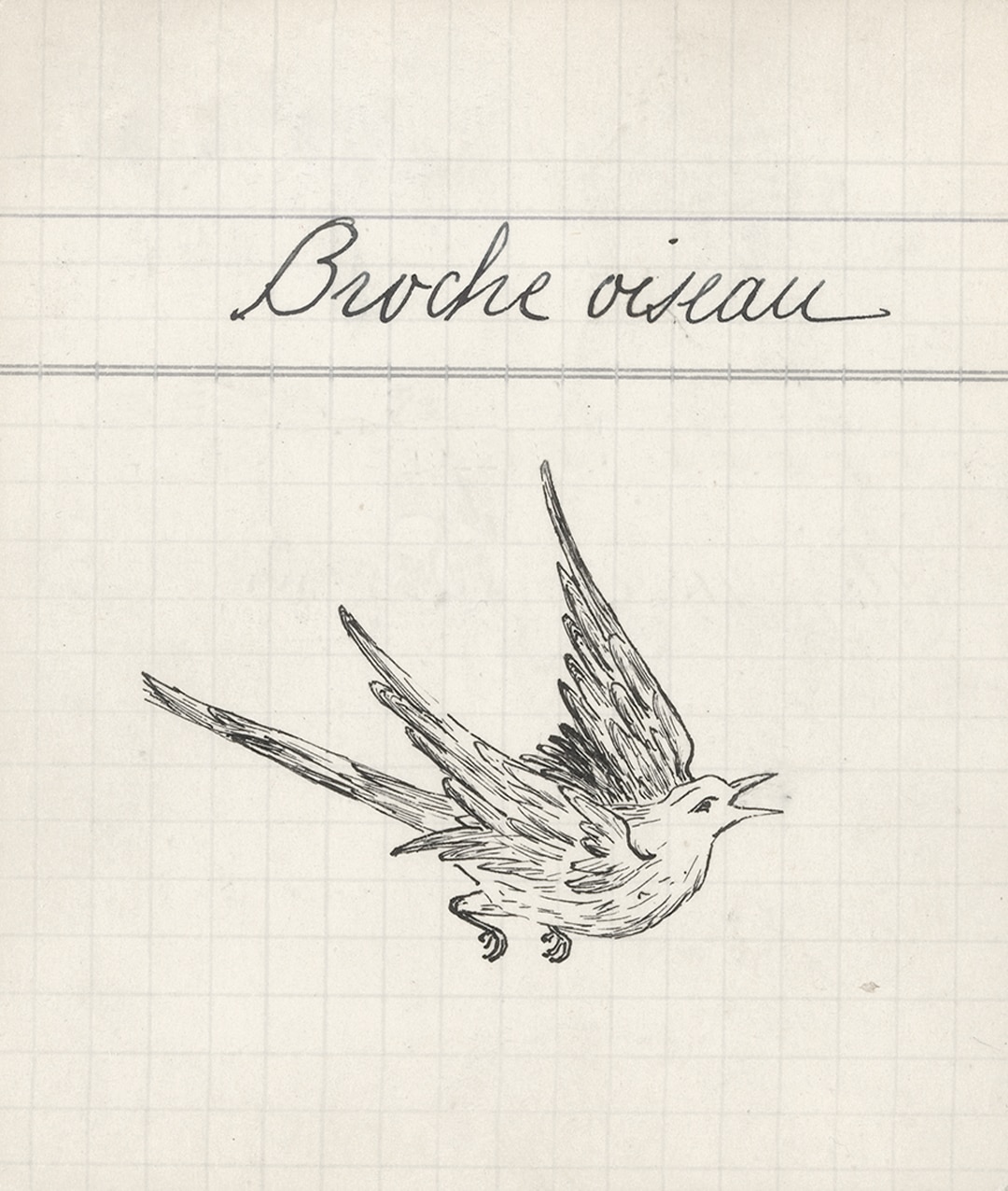

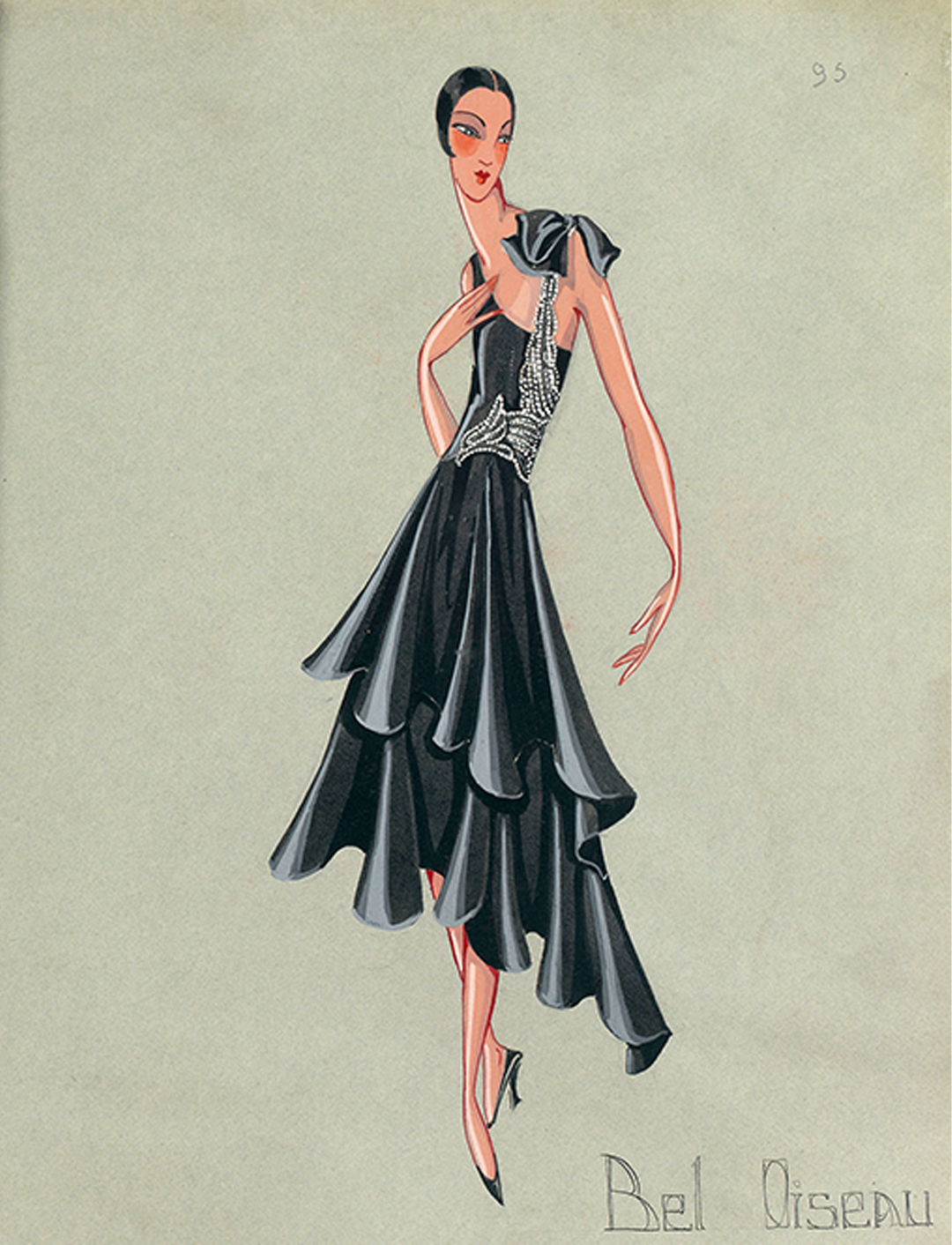

This productive association was also seen in shared sources of inspiration. Embroidery was a significant example. As a technique of ornamenting women’s clothing, embroidery was at its height in the 1920s, and employed a decorative lexicon identical to that of jewelry, with decoration that was naturalist, Modernist or Art Deco, and motifs that were non-European or ethnographic.16See Zelda Egler, “La Broderie dans les années 1920,” in Olivier Saillard, Anne Zazzo, eds., Paris Haute Couture, (Paris: Skira Flammarion, 2012): 122-125. In 1928, Maisons Van Cleef & Arpels and Jeanne Lanvin both came up with a creation inspired by the same motif, namely a bird in full flight, sparkling with a thousand fires, those of diamonds for the Bird brooch by Van Cleef & Arpels and those of crystal for the Bel Oiseau dress by Jeanne Lanvin. The bird moved across the upper half of the dress, one wing extended to form a strap. As with jewelry at this time, dresses gained in volume, here with the use of overlapping flounces for the lower half of the dress. Jewelry and clothes were developing in the same direction, creating a silhouette.

Women’s emancipation through men’s clothing

In addition to this shared aim, both jewelry and clothes were bearers of values. The tie-necklace, for instance, was not just the transposition of a textile accessory into a precious object; it was also in line with the movement for the emancipation of women that emerged in the 1920s. The twenties were associated with the flapper,17A figure inspired by Victor Margueritte’s novel La Garçonne, originally published by Ernest Flammarion in 1922. an androgynous figure who appropriated the male wardrobe in a literal sense, thereby acquiring new freedom that exceeded the codes of the time.

While flappers dressed as men remained marginal, there was nonetheless an overall elimination of the female figure in favor of a straight, elongated, tubular profile. Some women, keen to display their emancipation, adhered to this fashion by quite simply adopting a few so-called masculine accessories like the tie, which they usually combined with comfortable knitted outfits.

In the late 1920s, the artistic director of Van Cleef & Arpels, Renée Puissant, the daughter of Esther Arpels and Alfred Van Cleef, went along with this movement by creating tie-necklaces. The Maison was the only jewelry house to present this novel form of jewelry at the 1929 fair dedicated to the jewelry arts and goldsmithery, held at the Palais Galliera. Its tie-necklaces drew upon the original textile object fairly closely, while also following the jewelry fashions of the moment. In the late 1940s, the Maison therefore created a Cord version- that combined both genre and era.

Complementary arts

While this union between clothing and jewelry seemed intrinsic to fashion, the Mai- son’s jewelers embodied and expressed it with astonishing resourcefulness and virtuosity. As André de Fouquières pointed out, in reference to Van Cleef & Arpels’ creations: “Jewelry is not merely finery, a luxury object, but the accompaniment to fashion.”18André de Fouquières, “Le bijou et la mode. Quelques pages extraites de Femina par Van Cleef & Arpels,” Femina (January 1933): 2. Van Cleef & Arpels thus models its own aesthetic on the woman’s body: the Van Cleef & Arpels silhouette.