Marion Mouchard

Historical revivalism is the practice of appropriating styles of the past, and it came into its own, theoretically and artistically, in the nineteenth century. Until then, references had been limited to Greek and Roman antiquity, but henceforth embraced the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and the eighteenth century1For a French study dedicated to the revivals within the decorative arts of the nineteenth century, see: Anne Dion- Tenenbaum, Audrey Cay-Mazuel, Revivals. L’historicisme dans les arts décoratifs français au XIXe siècle (Revivalism in the French Decorative Arts of the Nineteenth Century), Paris, Les Arts Décoratifs, 2020.

The arts of these former eras afforded a vast repertoire of forms from which all the artistic fields of the nineteenth century drew. The decorative arts pursued and enlarged this historical eclecticism during the following century. The work of Van Cleef & Arpels contributed to this as early as 1906. The first debit and stock books show us the extent to which the Maison was inspired by the eighteenth century. During the second half of the 1910s, the Maison regularly commercialized so-called “Louis XVI”2Debit book, 1906-1907, N° 1960, Van Cleef & Arpels Archives, Paris. vest buttons and nécessaires. Borrowing from the arts of previous centuries increased during the 1920s, as spurred on by Émile Puissant. But the advent of Modernism in the early 1930s—a movement characterized by its ahistorical nature—signaled a pause in the references to the past seen in the Maison’s creations. By the late 1930s, however, revivalism was back, reestablishing itself throughout the jewelry production of the 1940s and 1950s. While the eras under consideration—the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and even the early twentieth century—remained the same, the way they were read and interpreted varied from one decade to another according to the fluctuating intentions and values with which they were invested.

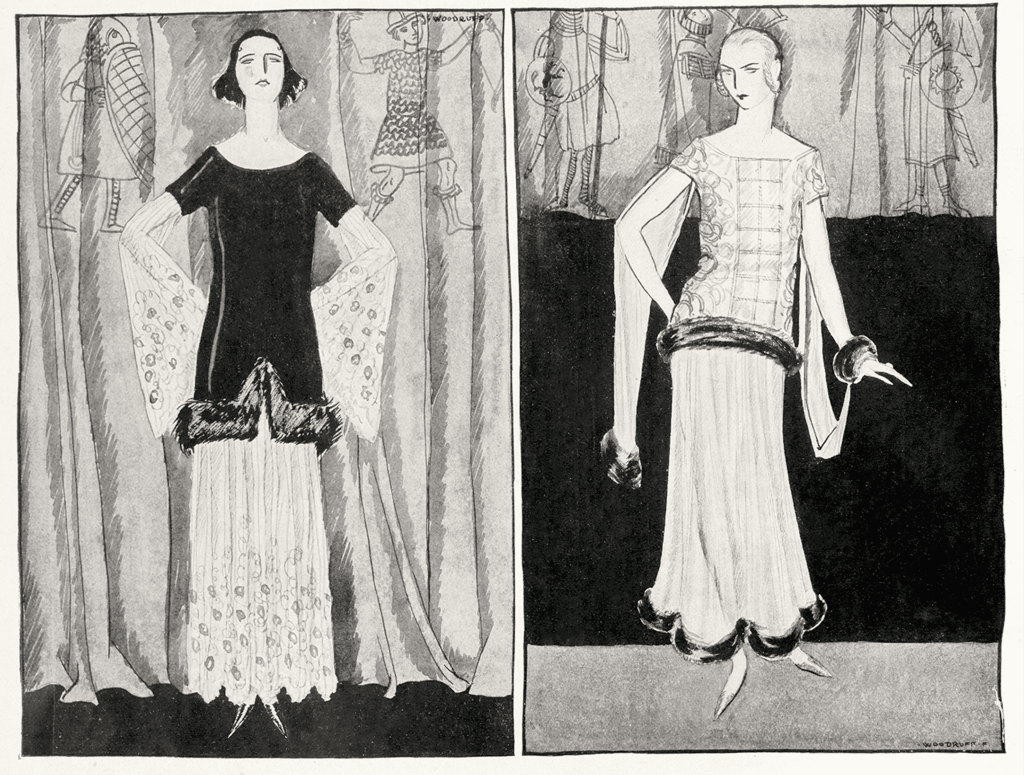

Rediscovering the Middle Ages

From the nineteenth century to the early twentieth century, France showed a renewed interest in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. The designs of couturiers such as Jeanne Lanvin and Paul Poiret drew on an eclectic repertory that “was not limited to a single era”: “echoes of the Italian Renaissance, and the lines and decoration of the Middle Ages were to be found”.3M.H., “Lanvin et la mode à travers l’histoire” (Lanvin and Fashion through History), Vogue Paris, November 15, 1920, p. 11.

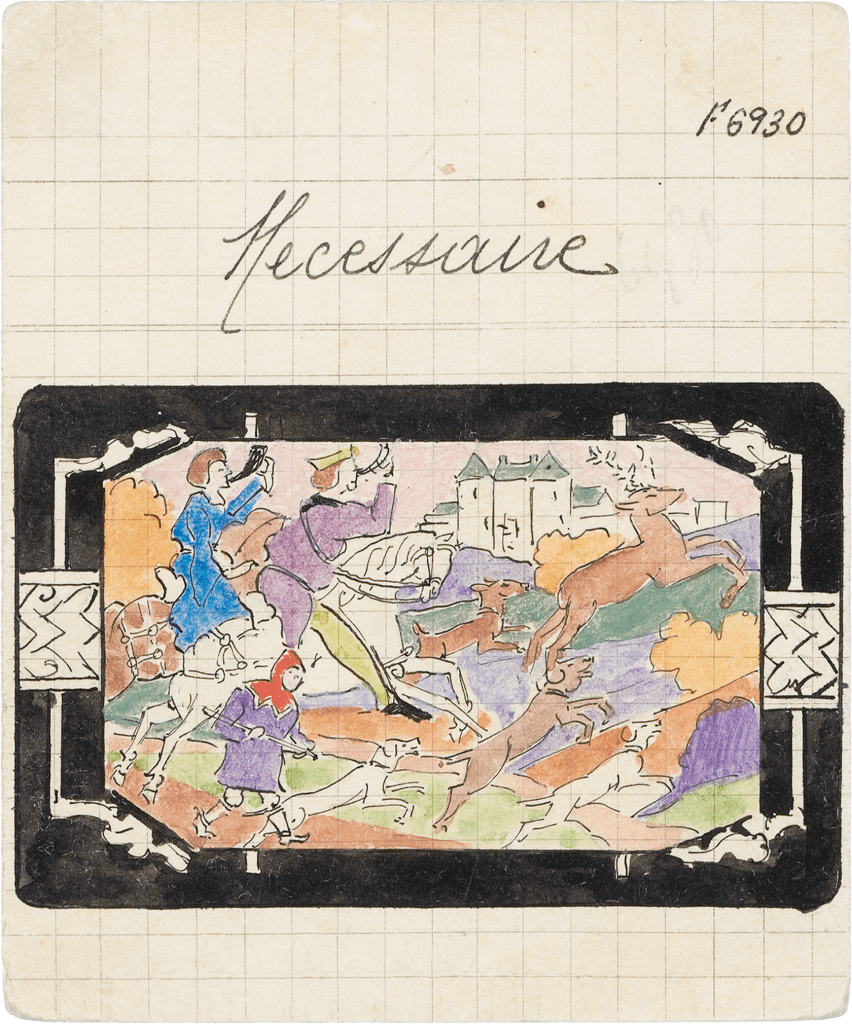

The earliest signs of a taste for medieval arts were seen in the decoration of cigarette cases and nécessaires created by Van Cleef & Arpels between 1925 and 1926. The large flat surfaces afforded by this type of object favored decoration in the form of narrative panels inspired by medieval works. These panels were often colored by the use of polychrome mother-of-pearl inlay or, more rarely, by ornamental stones. The Bayeux Tapestry provided a wealth of iconography, as did the literary arts.

Hunting scenes, commonly found in medieval times both in the East and in the West, served as a model for a nécessaire. The scene is reminiscent of illuminations by Gaston Phébus, and shows a stag hunt led by three hunters—two on horseback sounding the horn and one on foot—while a pack of hounds chases a stag through a forested landscape with a castle in the background. Motifs conveying the stylization and rich color palette of the Middle Ages thus enhanced Art Deco’s own vast stylistic repertoire.

References to the Renaissance

It was not until the second half of the 1930s, however, that revivalist references were once again found in Van Cleef & Arpels’ production. These contributed to the new esthetic championed by the Maison at the Paris Exposition internationale des arts et des techniques appliqués à la vie moderne in 1937.

For this event, the Maison presented the Medici necklace, with its stylized design reminiscent of sixteenth-and seventeenth-century ruffs, majestically placed in the center of its display. The close-fitting necklace is composed of a ribbon of calibrated diamonds overlaid with a “collar” of graduated baguette-cut diamonds. This form of necklace, worn high around the neck like a fabric collar, was immensely popular during the 1940s. The similarity to the fluted ruffs of the Renaissance was enhanced by the formal simplification of the Medici necklace giving way to folds of yellow gold lace.

Works of art as sources of inspiration

Even more exact historical references can be related to various works of art in museums. The two Unicorn clips in the Patrimonial Collection dating from 1948 are three-dimensional adaptations of The Unicorn in Captivity, a tapestry conserved at The Cloisters in New York.

Similarly, the Gladiator clip, dating from 1956, is an interpretation of The Canning Jewel, a pendant on show in the Victoria & Albert Museum in London.4When this pendant was acquired by the Victoria & Albert Museum in 1931, it was thought to date from around 1580. When it was re-evaluated in 1986, however, it was considered to be an imitation Renaissance piece dating from the second half of the nineteenth century. Van Cleef & Arpels’ Gladiator clip therefore illustrates the sometimes recurrent nature of revivalism. While replacing the mythological figure of Triton with that of a gladiator, the figure’s posture nonetheless remains the same. In place of the gorgoneion held by the Triton, the gladiator brandishes a yellow gold and diamond sword, as well as a shield adorned with a star motif of yellow gold, diamonds, and rubies, edged with twisted yellow gold thread. His head is also different, composed of a single rose-cut diamond set in gadrooned yellow gold.

While the techniques used in these two pieces may differ, the desire to retain the chromatic richness of the original enamels is seen here in the use of emeralds, rubies, and turquoises mounted on yellow gold. The irregularities of the baroque pearl, used to render the muscular torso, pay tribute to the creativity of Renaissance jewelry.

The influence of the 18th century on art and jewelry

Since the Second Empire (1852–1870), the arts in France had looked to the eighteenth century for inspiration. This taste for the styles of Louis XV and Louis XVI lasted until the mid-twentieth century, despite the emergence of various stylistic movements such as Art Nouveau and then Modernism, which strongly opposed these reminiscences considered backward-looking. The artistic tradition inherited from the eighteenth century in France was a favorite source of inspiration for the artists of the first phase of Art Deco, as well as being the origin of a counterpoint to Modernism in the 1930s. The fashion arts were full of “reminiscences,” with longer, fuller skirts, in keeping with the return to favor of the Enlightenment which “gave us Watteau’s baskets, leotards, […] [and] coats”.5Anonymous, “Panorama des lignes et couleurs dominantes des collections,” Album de la mode du Figaro, no. 2 (Summer 1943): 70–71.

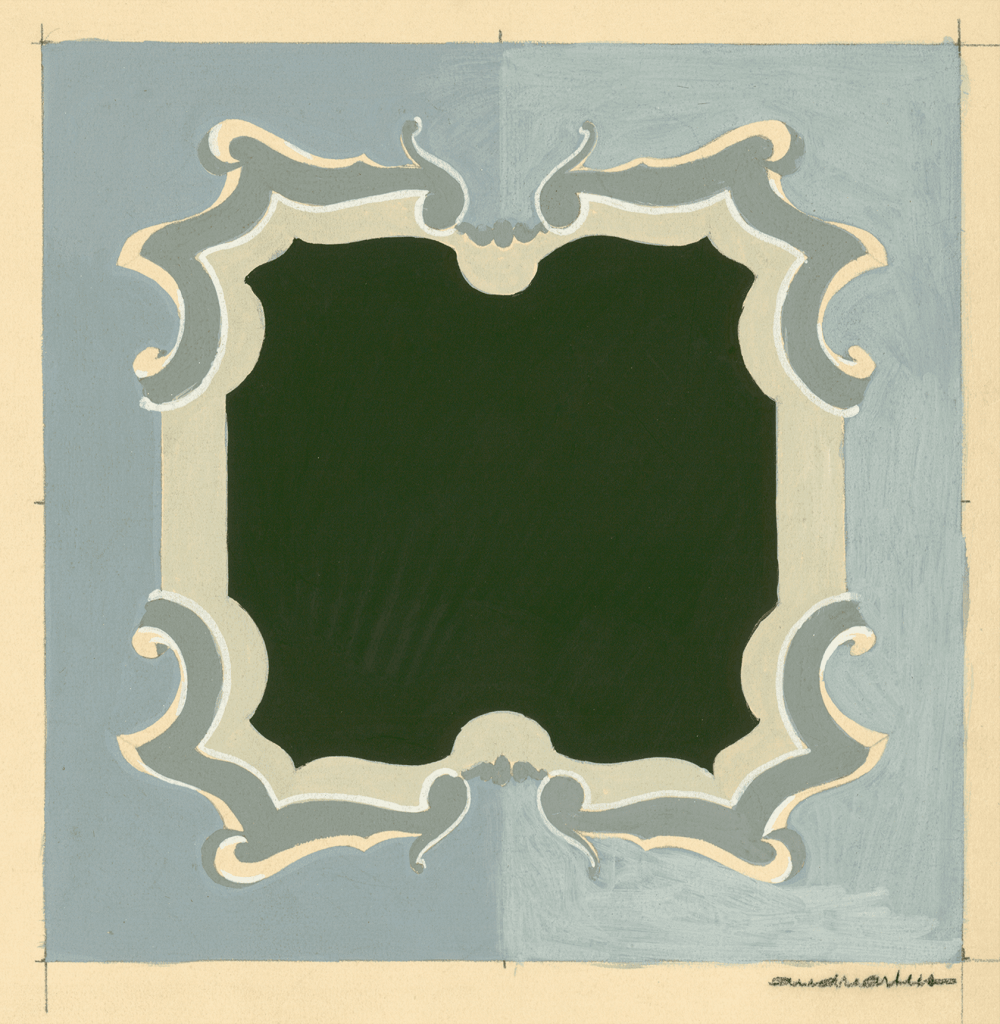

In the work of the architect and interior decorator Emilio Terry, references to the past were endowed with a degree of dreaminess, resulting in architectural fantasies that reconnected with the old masters, from Andrea Palladio to Claude-Nicolas Ledoux.6Pierre Arizzoli-Clémentel, Emilio Terry (1890-1969), Architecte et décorateur (Montreuil: Gourcuff Gradenigo, 2013). These works also revived the exuberant ornamental repertory of the Rococo style, reinterpreting so-called “grotto furniture” and covering interiors, gardens, and facades with coral and shells.

In keeping with this poetic reinterpretation of the eighteenth century, the bird cage, also known as the Maison d’Hortense was a singular project quite unlike anything else within Van Cleef & Arpels’ creative output. Conceived in 1935 as a precious vivarium intended for a tree frog, it was transformed into an art object housing birds made of beryl. The preparatory drawings for this yellow gold cage hint at rocky formations in lapis lazuli, dotted with branches of coral and shell-shaped feeders. The various sketches depicting a cage in the shape of a piece of fruit, a pavilion, and a trellis illustrate a form of revivalism tinged with Surrealism characteristic of the 1930s.

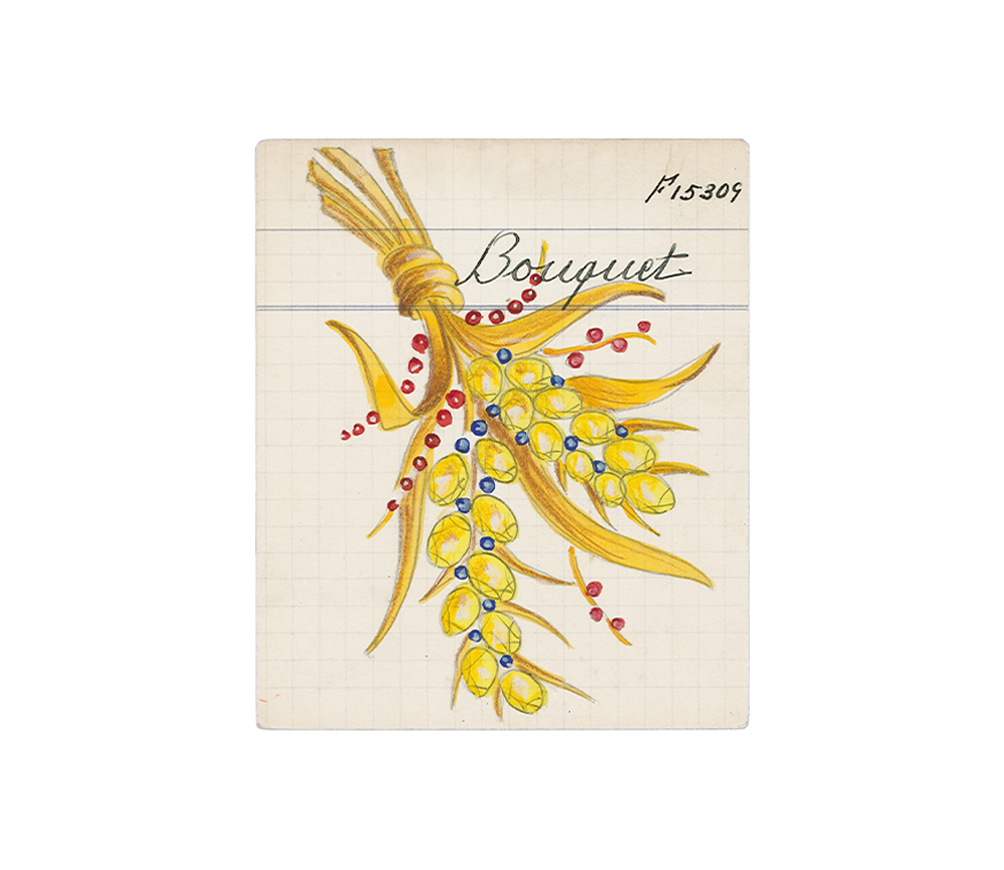

The flower motif

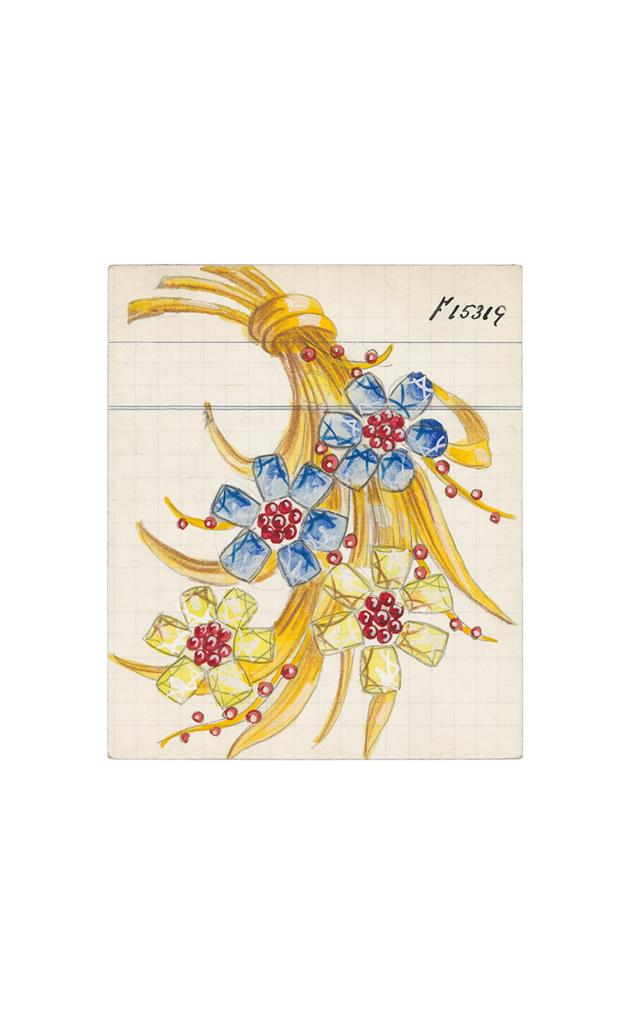

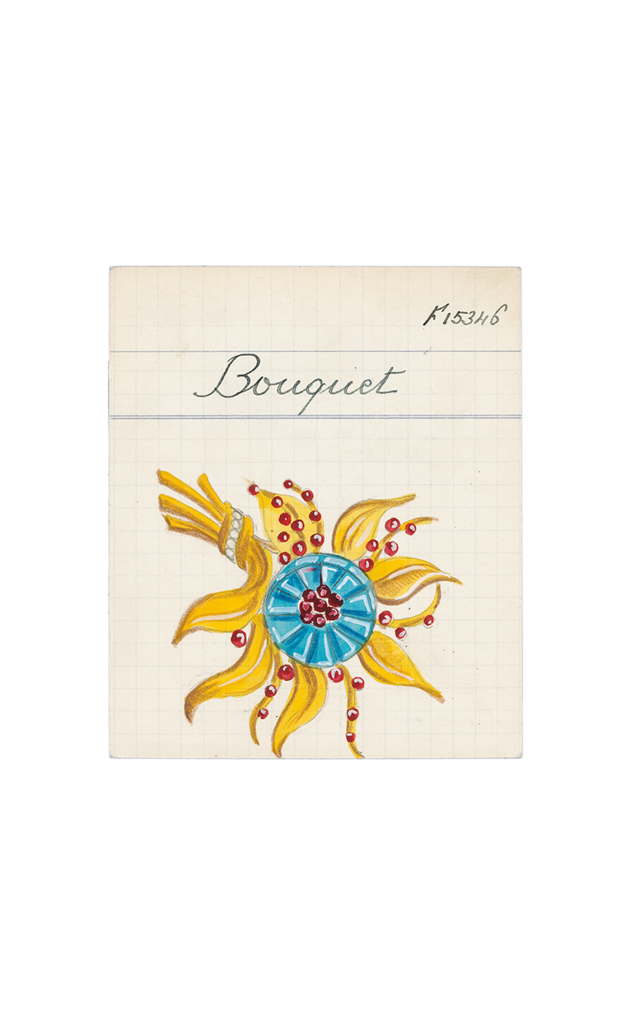

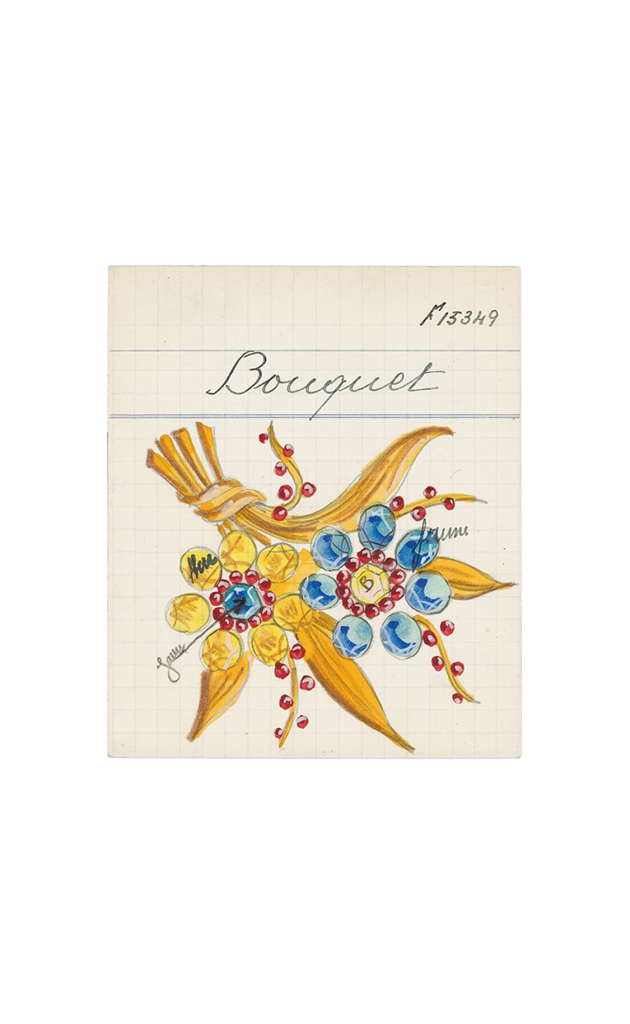

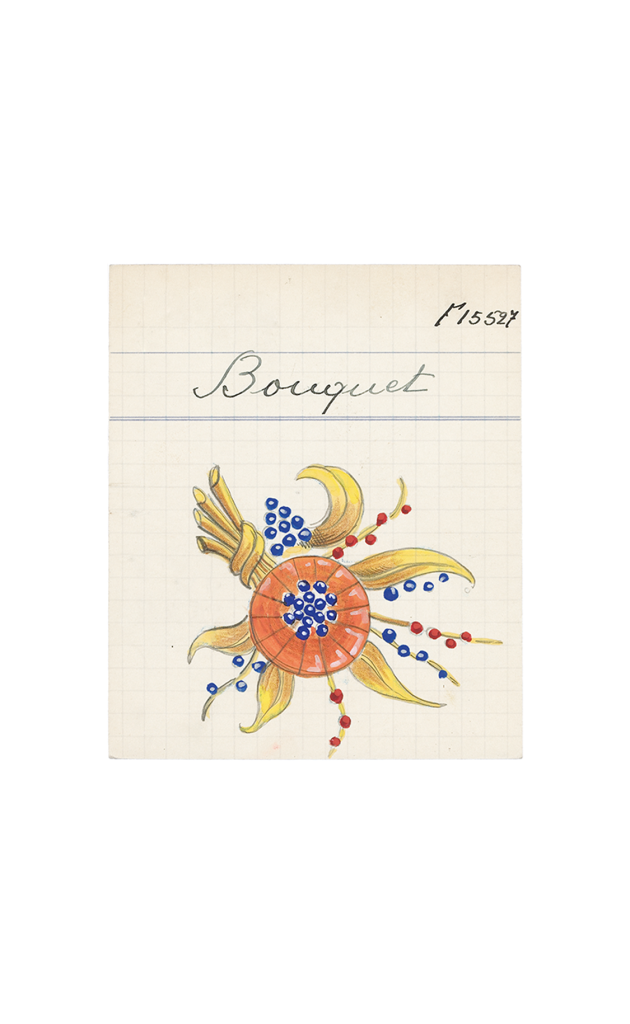

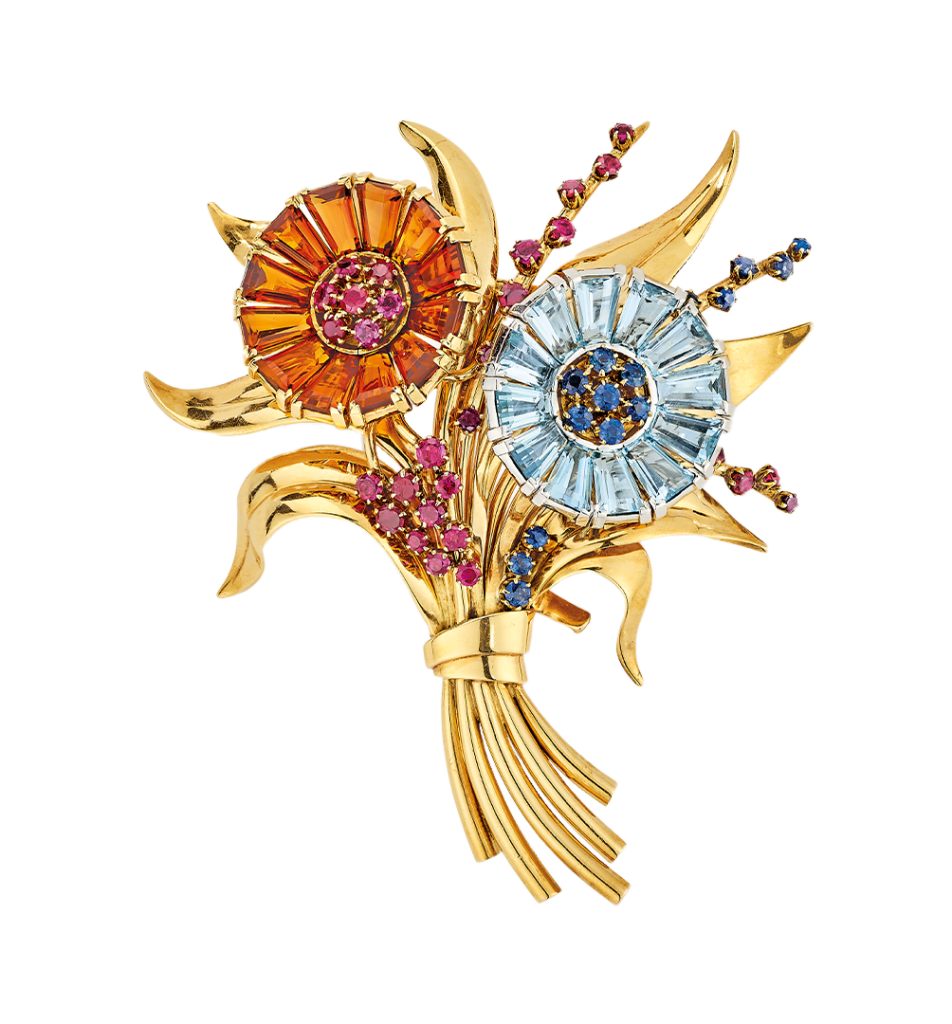

While Van Cleef & Arpels adhered to the principles defended by the Union des artistes modernes (UAM), it was no less attentive to the time-honored iconography of jewelry. The foremost of these was the flower motif, transposed to the techniques and materials of jewelry, which, in the 1930s, was given a new lease on life. “Van Cleef and Arpels drew its inspiration [at that time] from floral motifs rendered with the utmost delicacy. They used gold and multicolored stones to achieve this”7L’Art et la mode, no. 2668 (1941): 65. : yellow and blue sapphires, rubies, aquamarines, and topazes. The Maison fashioned bouquets modeled on stomachers created by the master jewelers of the eighteenth century. They were composed of one or more “rosettes” within “irregular-shaped sprays”8L’Art et la mode, no. 2668 (1941): 65. of buds and leaves. The stalks were bound by yellow gold ties, knotted ribbons, or lacelike cockades.

Bouquet clips

Ribbons and bows

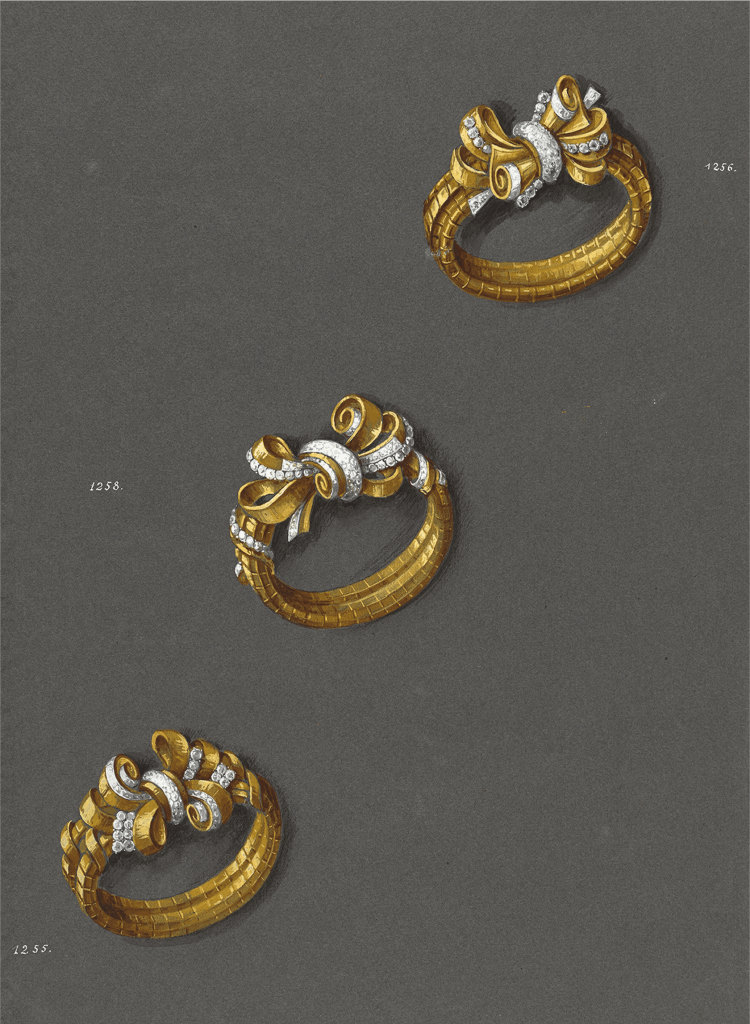

Individual bows, jabots, and lace corollas (small collars) were also made at this time. Bows appeared as an ornamental element in the seventeenth century and were one of the most recurrent features in jewelry treatises of the eighteenth century, when they were worn alone on the front of the bodice or suspended from a stomacher. The Bow clips and brooches, which were highly stylized during the Art Deco period, displayed a great sense of detail from the late 1930s. The complex networks of yellow gold threads rendered the delicate lacework with the same precision as the jewelers of the eighteenth century. The piercing technique replaced the openwork mounts of the Ancien Régime.

From 1944, a series of clips broke with these delicate textile weaves. Ribbons were made of solid, polished yellow gold terminating in volutes. They looked to a Neo-Baroque style similar to that developed by the interior designers of the Société des décorateurs français.

These clips were also made in bracelet form, adjusted on chains similar to Tubogas ones. The connection with the eighteenth century was confirmed in images used for marketing developed by the Maison, as seen in one of its advertisements published in 1944. In the foreground, we see a woman with her hair swept back off her neck wearing a dress with pleated shoulders and a Bow bracelet around her wrist. In the background is the work Marie-Antoinette with a rose, a portrait painted by Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun in 1783. This juxtaposition of the two women highlights the proclaimed stylistic link between the two eras.

The Cord jewelry

This Bow design was also adapted for a necklace, in 1945. Ribbons of polished yellow gold, outlined with brilliants, are coiled around a short mesh necklace forming two loops ending in tassels, another motif borrowed from the ornamental repertory of the eighteenth century. Gold threadwork came into its own during Louis XIV’s reign, when it was used for court furnishings and costumes, before being adopted as a decorative motif in the eighteenth century. It then became a pattern for designers in the 1940s, who, like the master metalworker Gilbert Poillerat, drew upon the artistic repertory of the Ancien Régime. On two other similar necklaces, the ribbon coils gave way to interlaced designs and scrolls, calling upon a wider Neoclassical vocabulary.

It was in the Cord jewelry range, first created in 1946, that Van Cleef & Arpels made the greatest use of trimmings traditionally used for clothing and furnishings. Early versions of the Cord necklace featured capuchin knots at the end of the gold cord, while later versions suspended tassels on small chains.

These were followed toward the end of the decade by “cascade” earrings, Ludo bracelets and necklaces with three rows of fringed cords, and “rope tassel” necklaces.

“Old-style” jewelry

A couple of rare examples borrowed both decorative and formal elements from the past. Between 1948 and the early 1950s, “old-style” powder compacts in yellow gold were enhanced with engine-turned latticed panels surmounted with decorative carving, reminiscent of Louis XV snuffboxes. This example illustrates a taste for the past that was particularly concerned with faithfully reproducing the model itself, a trend that was to continue until the 1950s. The coexistence of both imaginary and more literal revivalist styles was also seen in certain jewelry sets that were reminiscent of the grand jewelry tradition in terms of design.

From the late 1930s, “old-style” necklaces set with oval sapphires surrounded by brilliants in the form of daisies9The most popular ring in eighteenth-century France was the so-called “Pompadour” or “daisy” ring which had a bezel-set stone in the middle, with smaller stones around it. were to be seen along with matching bracelets and pendant earrings, akin to the grand jewelry sets of the eighteenth century. These pieces were probably inspired by the old and even, on occasion, historical pieces of jewelry purchased by the Maison. Such was the case for the Collier de la Liberté acquired by Van Cleef & Arpels in 1925 and a “Louis XVI” set—“a fine example of the jewelry of this period,” as a 1936 advertisement stated.10Anonymous, “Une magnifique parure historique,” Plaisir de France, June 1936, p. 12. A collerette, designed in 1949, used the same method for mounting pear-cut and faceted square emeralds surrounded by “antique-cut diamonds.” The popularity of these pieces during the second half of the 1940s and the following decade coincided with the revival of society events and the pomp accompanying them. They put the finishing touches to richly embroidered evening dresses designed by couturiers like Christian Dior, who looked to the extravagant conventions of the Ancien Régime.

Jewelry inspired by the 19th century

The nineteenth century, which took an avid interest in the arts of previous eras, itself became the subject of revivals. From the early 1920s, the costume arts, and in particular the designs of Jeanne Lanvin,11“Lanvin had already launched the Second Empire fashions last year to such success that she did not hesitate to continue them. […] Together with Poiret, they are the only major fashion houses to have maintained the wide hemline, the fullness of the skirts.” Extract from “Lanvin et la mode à travers l’histoire,” Vogue Paris, (November 15, 1920): 11. displayed a taste for the Second Empire. By the second half of the 1930s, this penchant was observed again in numerous “period dresses” that borrowed from “Romanticism” with their “Second Empire low necklines.”12Anonymous, “La Soie pour le soir,” Très parisien, no. 6 (1935): 10. Van Cleef & Arpels looked to the nineteenth century at the same time. This revivalism encouraged a formal and iconographic renaissance that enhanced and then replaced the geometric Art Deco style and Modernism. The Bouquet clips and brooches were part of this “Romantic”13“Bouquets très romantiques,” La Femme chic (1946). trend of the 1930s and 1940s.

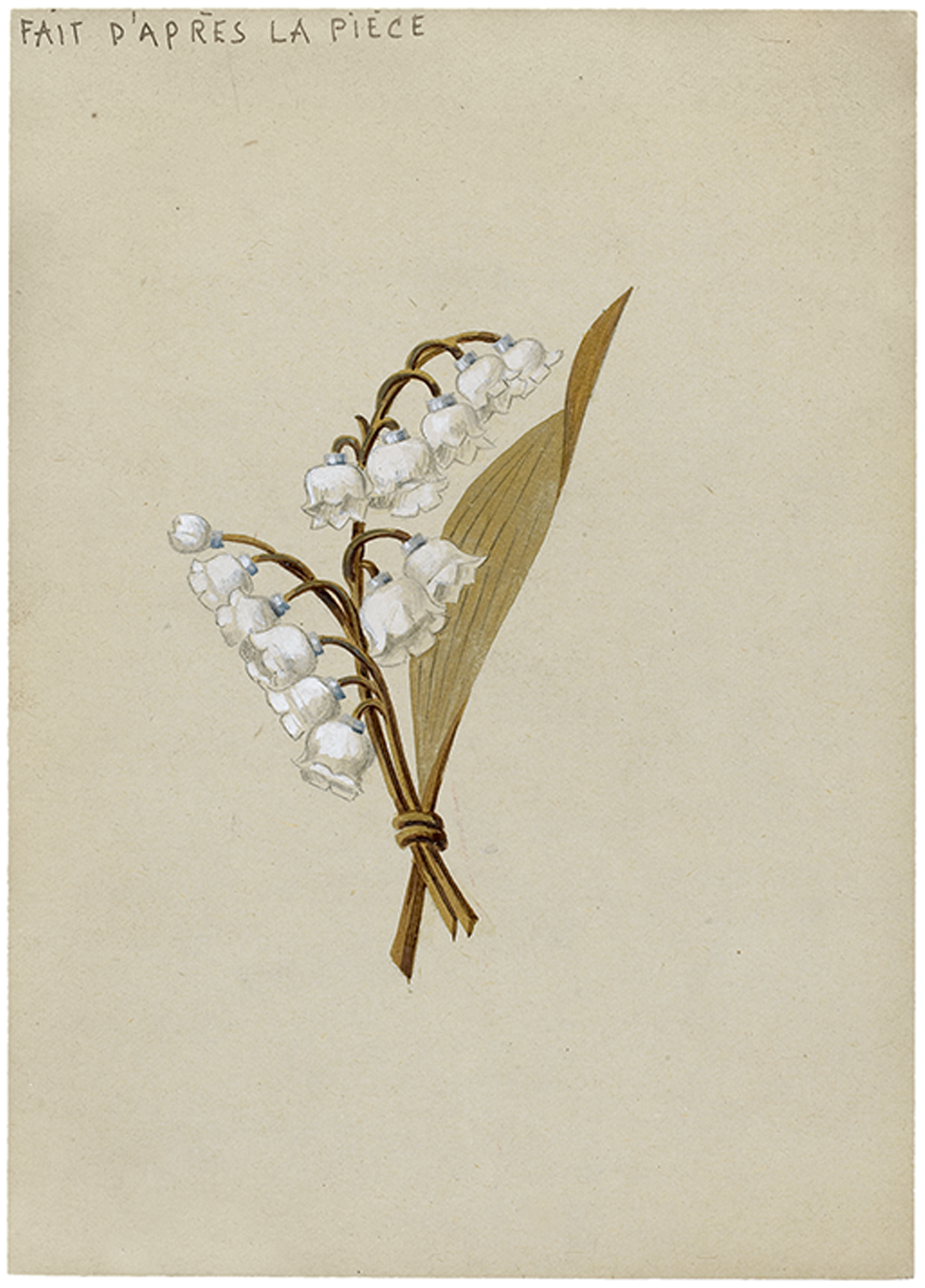

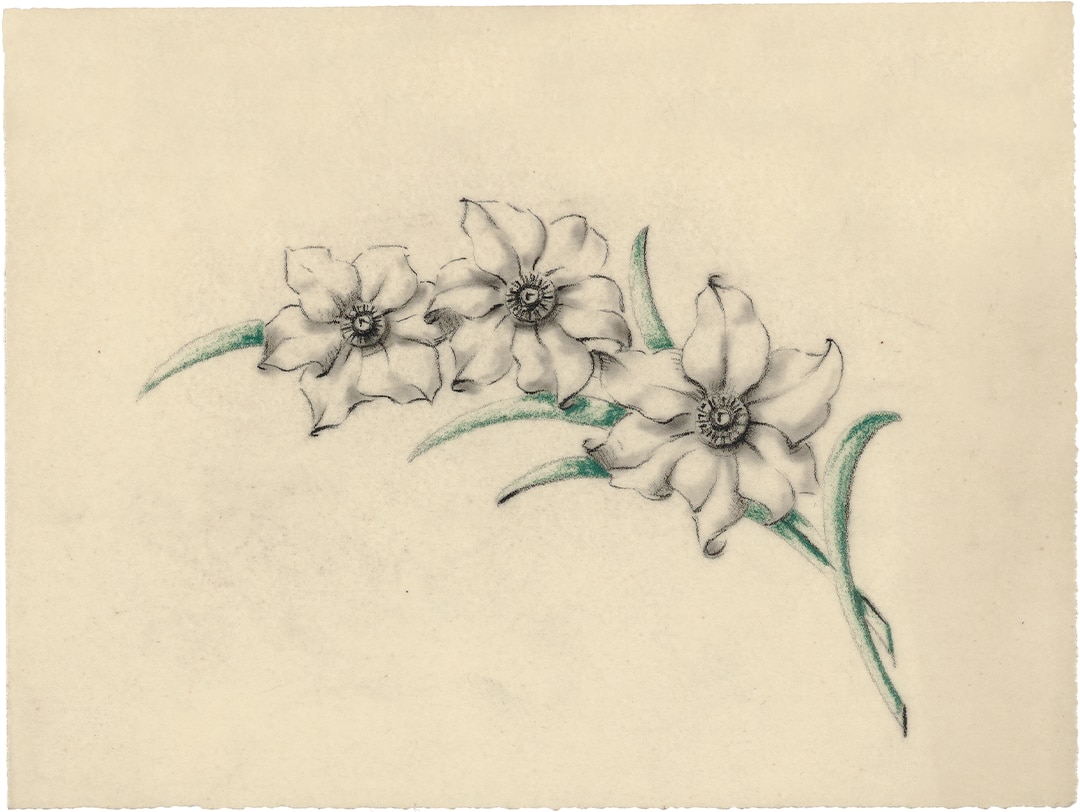

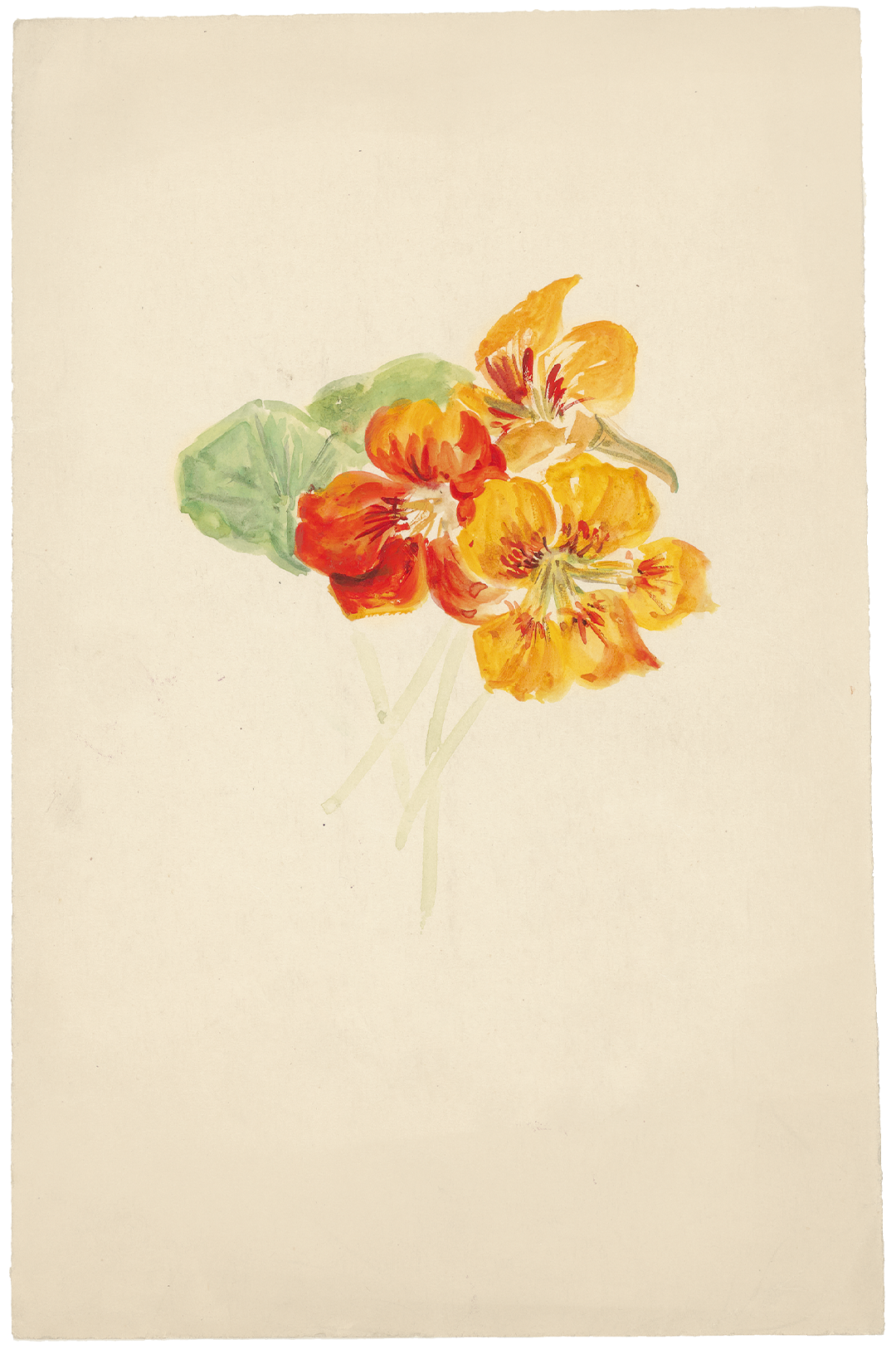

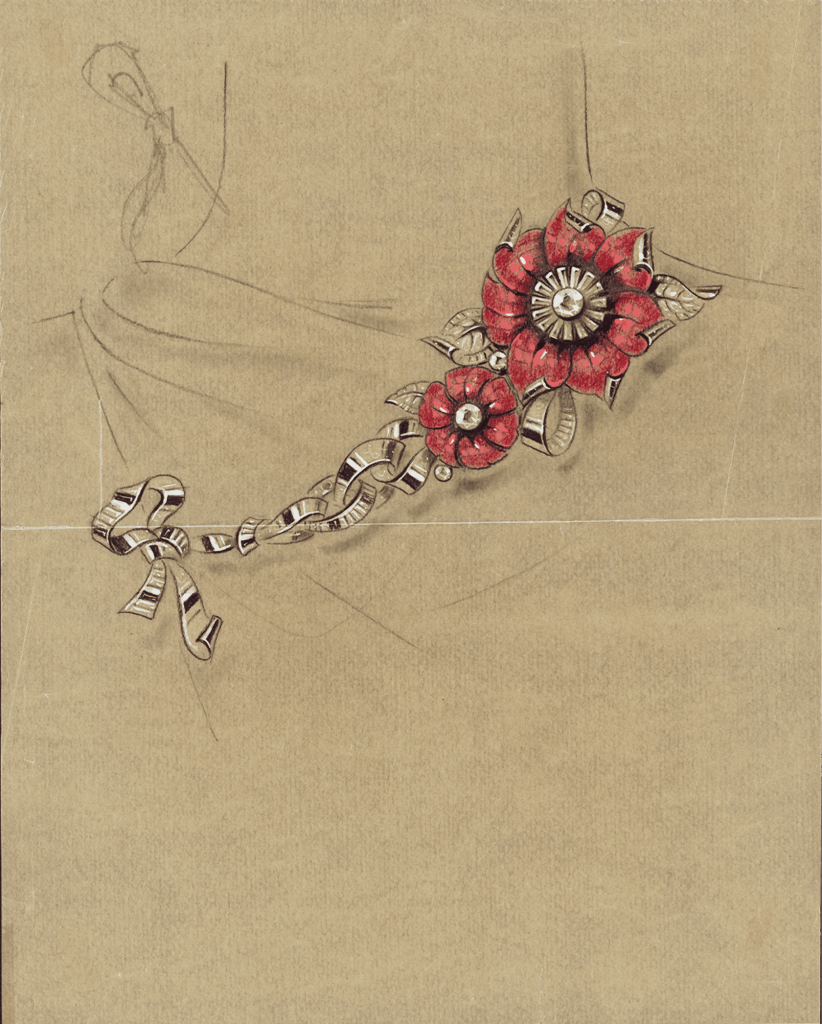

The jewelry arts of the nineteenth century afforded a vast floral and plant repertoire, as did those of the eighteenth century before it. But while the latter were rather fanciful, the former were typified by their naturalism. Countless pieces displayed a heightened sense of realism whereby actual flower types could be recognized: clips and brooches with buttercups, daisies, poppies, violets, lilies of the valley, wild roses, peonies, and anemones are examples of this faithful observation of flora, as in the previous century. Indeed, some of the preparatory gouachés resembled botanical studies rather more than jewelry projects. The legacy of the nineteenth century can be seen as much in the layout of the composition— one or more flowerheads placed in the middle, flanked by leafy branches—as in the jewelry techniques employed in the quest for faithful representation. The leaves and their movement were delicately transcribed by openwork mounts that held the claw-set round diamonds. Some pieces depicted the flowers in a manner akin to nineteenth-century jewelry while others played on the contrasts between the naturalism of the plants and the stylization of the floral motif, combining the knowledge of previous centuries with contemporary innovations.

Historicism and transformability

Revivalism was therefore very much a factor in the return “to [a form of] ornamentation that was closer to nature”(19) that occurred in the latter half of the 1930s. In parallel with this profound iconographic breakthrough, the return of technical and formal characteristics of nineteenth-century floral motifs was also observed. Many Van Cleef & Arpels brooches produced at this time with floral motifs, for example, had identical transformation systems to those found on Second Empire brooches.14Plaisir de France (December 1936): 43. In several outstanding pieces from the second half of the 1930s, techniques enabling their transformability were seen in opulent compositions reminiscent of cascading brooches from the previous century. This was the case for the Peony double clip, which was presented at the 1937 Paris Exposition universelle alongside the Medici necklace, emphasizing the new revivalist approach pursued by Van Cleef & Arpels.

Peony clip

That same year, the Maison created a “garland” of platinum ribbons formed of multiple coils highlighted with brilliant-cut and baguette-cut diamonds. The gouaché of an initial model shows that this composition was enhanced by two flowers with ruby petals and hearts of round diamonds surrounded by baguettes. It is probable that, like the 1937 peony clip, this floral ensemble could be detached from the rest of the garland. The final version of this model had a bow at either end, one of which was a brooch that could be worn separately and which held a cascade of ribbons in the same style.

An advertisement produced by Van Cleef & Arpels illustrates how such an ornament could be worn, with the two bow motifs attached as brooches to the lapels of a dress neckline, echoing the way jewelry was worn in the nineteenth century.

Projects for transformable “garlands,” the avatar of cascading brooches, continued through to the end of the 1940s, as seen in an “ivy garland clip” designed in 1947 or the “rose garland” clip created two years later.

Ludo bracelets

The Ludo bracelet, commercialized by the Maison from 1934, helped introduce greater variety into a repertory of forms dominated since the 1920s by the band bracelet. Wrapping a briquette mesh around the wrist, it marked the return to the flexible meshwork techniques of the Second Empire: “Once again, […] bracelets imitating fabric recalled the fact that Eugénie de Montijo was Empress of the French people.”15Anonymous, “Bijoux nobles reflets,” Album de la mode du Figaro, no. 1 (Winter 1942–1943): 70.

Furthermore, the Ludo models adopted the layering found in Jarretière (Garter) bracelets that had been popular during the previous century, with the use here of a more or less simplified belt buckle.

Not content with a single, faithful rendition of the past, Van Cleef & Arpels created a second version of the Ludo bracelet in which the legacy of the nineteenth century met the geometrical compositions of Modernism.

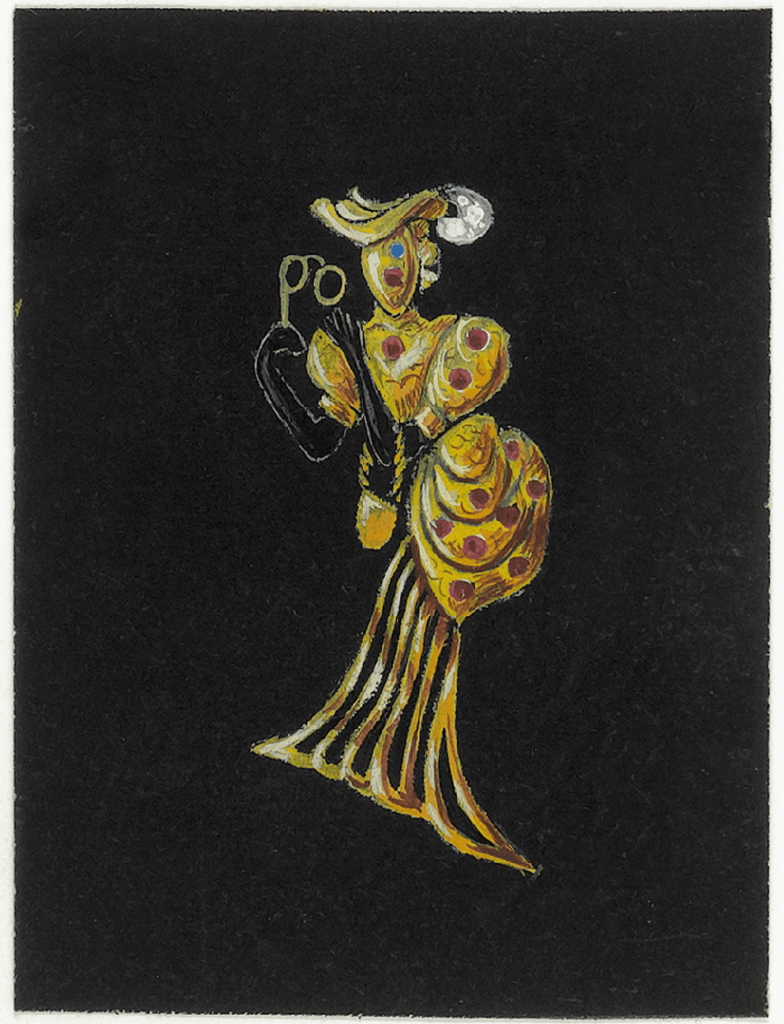

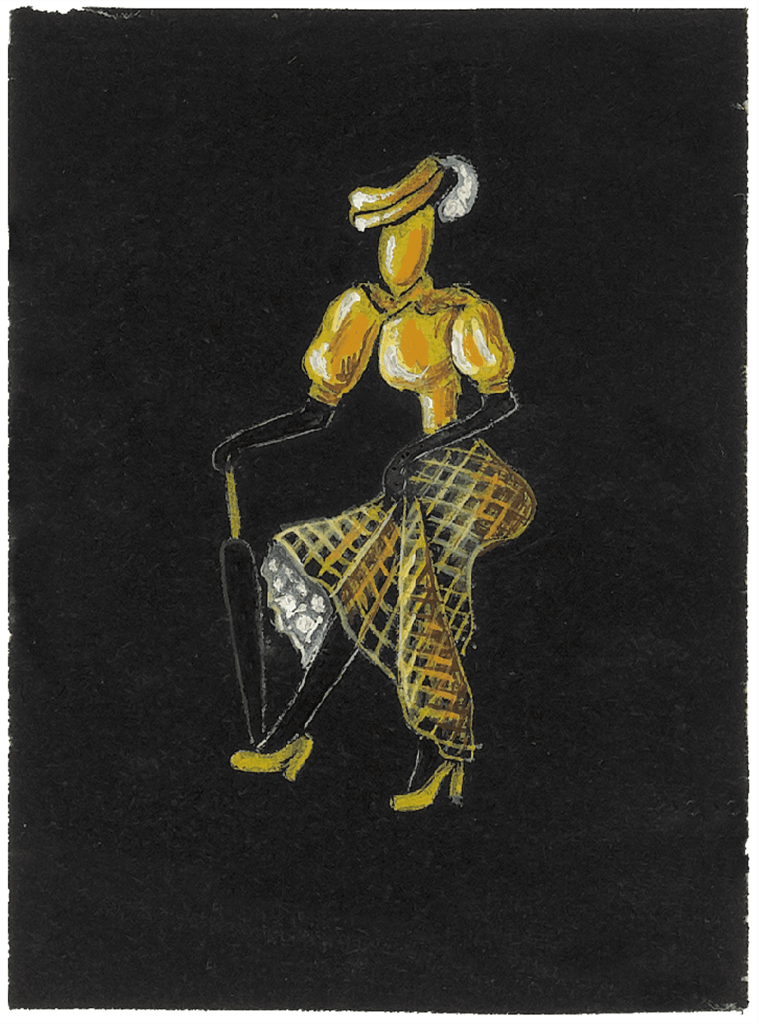

Third Republic and Belle Époque

From the 1940s, references moved ever further forward in date, to the point where people started becoming interested in the 1900s. The Third Republic, and then the Belle Époque became the new decorative references, with sinuous, close-fitting lines, sometimes enhanced by bustles, reappearing in sculpted silhouettes by Christian Dior and Cristóbal Balenciaga.

Calling upon the late nineteenth century, if not the early twentieth, meant a return to the idealized years preceding the two world wars. For couturiers, jewelers, and parfumers of the immediate postwar period, this in turn meant aligning themselves with the legacy of the bountiful years that witnessed the blossoming of Paris’ luxury industries. In this respect, revivalism contributed to reinstating Paris as the capital of the arts of appearance, with initiatives such as the Théâtre de la mode.

Clients saw this revivalism as reconnecting with Parisian elegance, which was considered to have disappeared since the First World War. The clips designed by Van Cleef & Arpels in late 1947, which took “Parisian women of 1900” as their subject, illustrate this phenomenon, as does the “1900” jewelry range.

While their name refers openly to the turn of the century, their iconography—an assemblage of wild roses—recalls the craftsmanship of late nineteenth-century jewelry.

Calling upon history in this way is also seen in the bouquet compositions of “blouse clips,” and the production of chokers or “dog collars,” an immensely popular jewelry form during the last decades of the nineteenth century.

Future historicisms in the second half of the 20th century

Whether scrupulously faithful or some- what illusory; sources of renewal or answers to a traditionalist taste—while often being vectors of national artistic assertions—the revivalist instances of the first half of the twentieth century undoubtedly perpetuated and evolved those of the previous century. Such examples of revivalism blended with other contemporary stylistic trends, contributing to the esthetic transformations of each decade. At the dawn of the 1950s, the return to favor of the 1900s heralded the numerous revivals that would accompany the art world during the second half of the century.