Marion Mouchard

Attributing talismanic benefits to pieces of jewelry dates back to classical antiquity. Thus it was for Roman bullae—gold or leather pendants containing amulets—suspended around the necks of young patricians for apotropaic reasons1Derived from the Greek apotropaios meaning “that which diverts (evil),” that wards off bad luck, protects against evil influence..

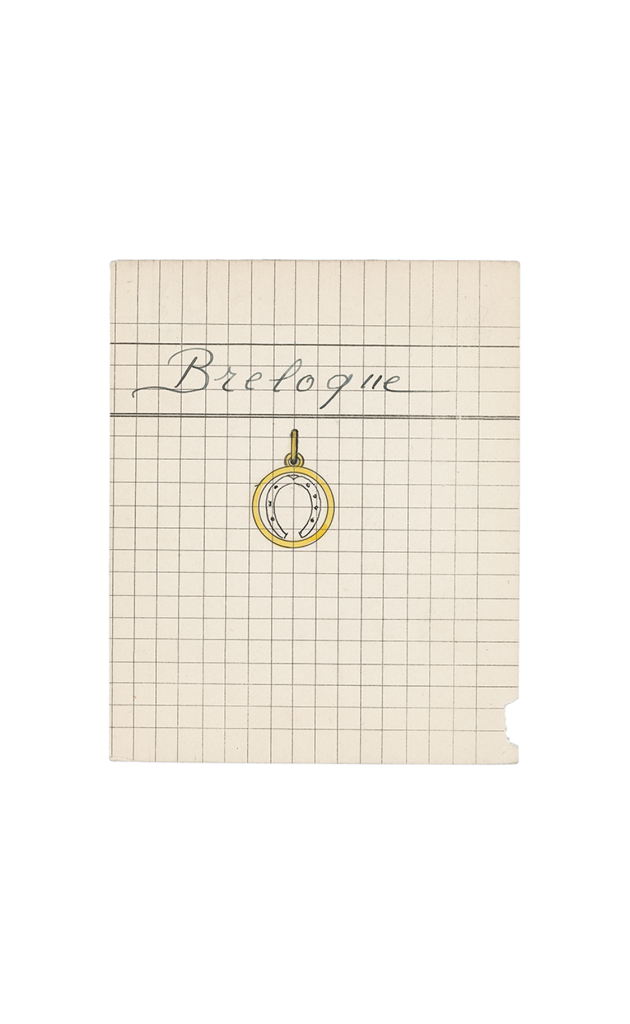

Van Cleef & Arpels talismanic. It has adopted a variety of motifs in a range of materials and colors evoking popular beliefs. We find the sale of a “horseshoe” medal,2Debit book. Paris, Van Cleef & Arpels Archives. for instance, listed in the debit book in March 1906. Similarly, several examples of “horseshoe brooches” featured in the stock books for 1910. Depending on whether they were “medium” or “small,” these were set with “53” or “47 brilliants,”3Stock book no. 2. Paris, Van Cleef & Arpels Archives. reflecting the taste of the period for white diamond jewelry. Numerous creations supposed to bring good luck to their owners were to follow on from these early pieces.

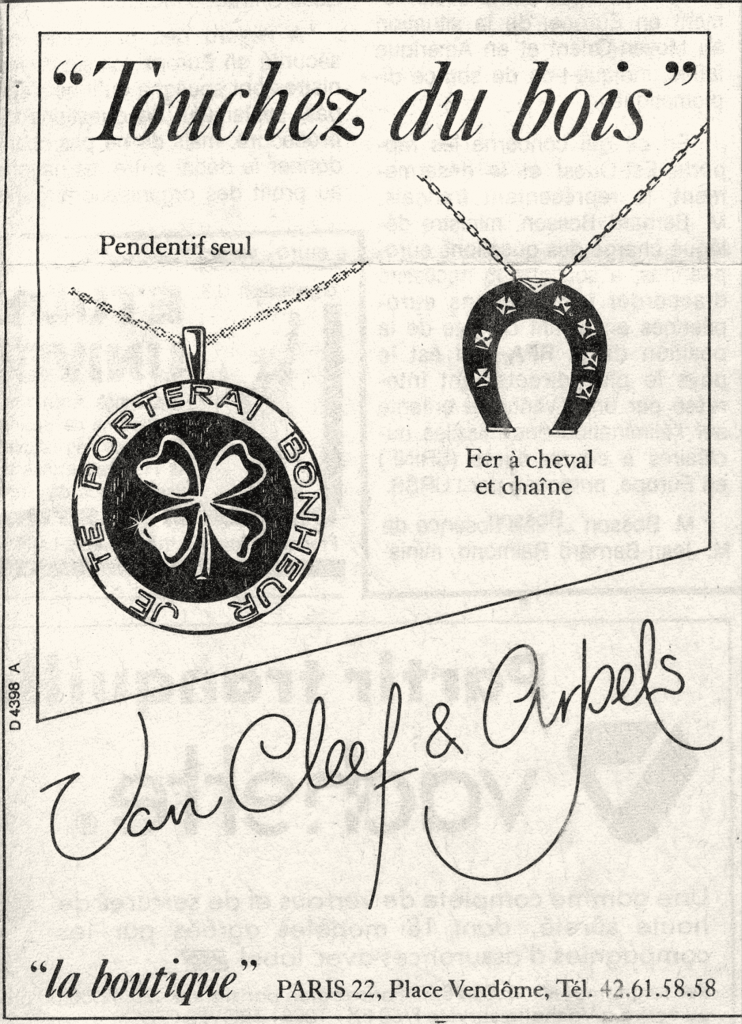

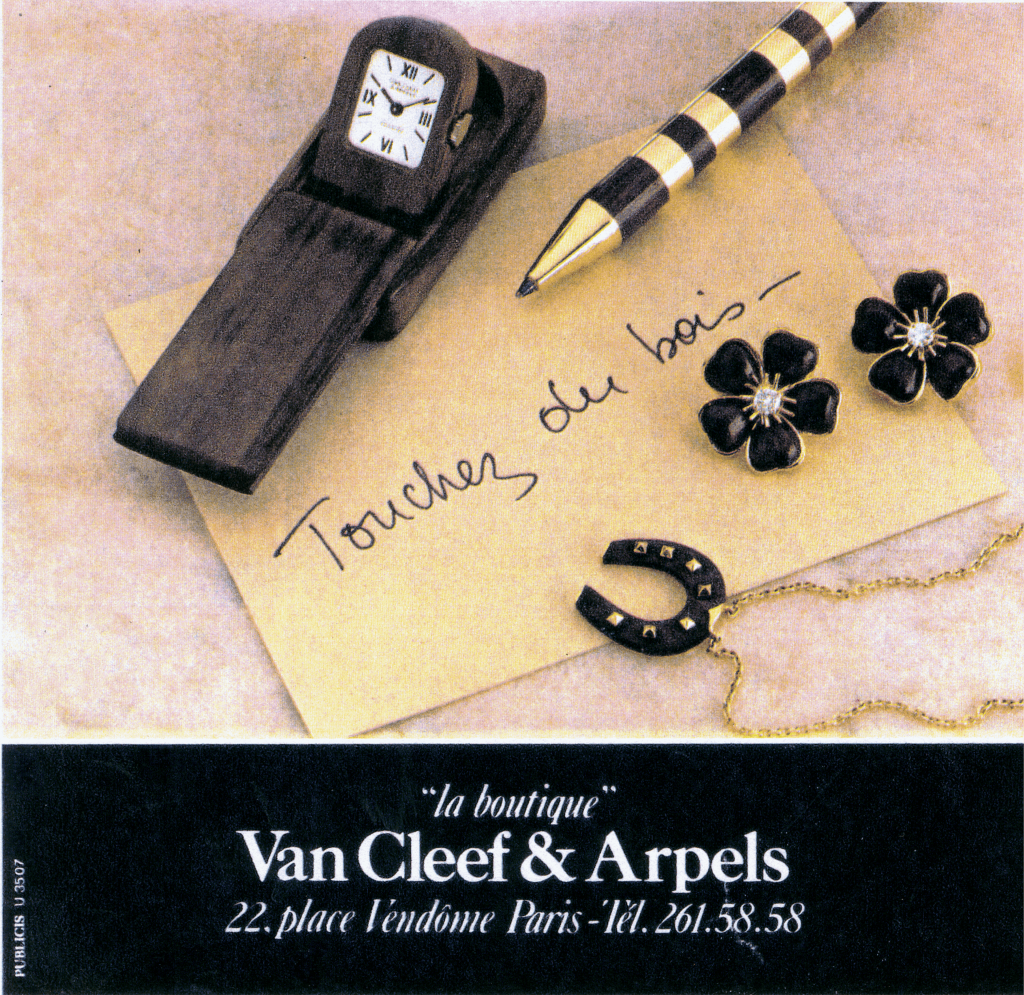

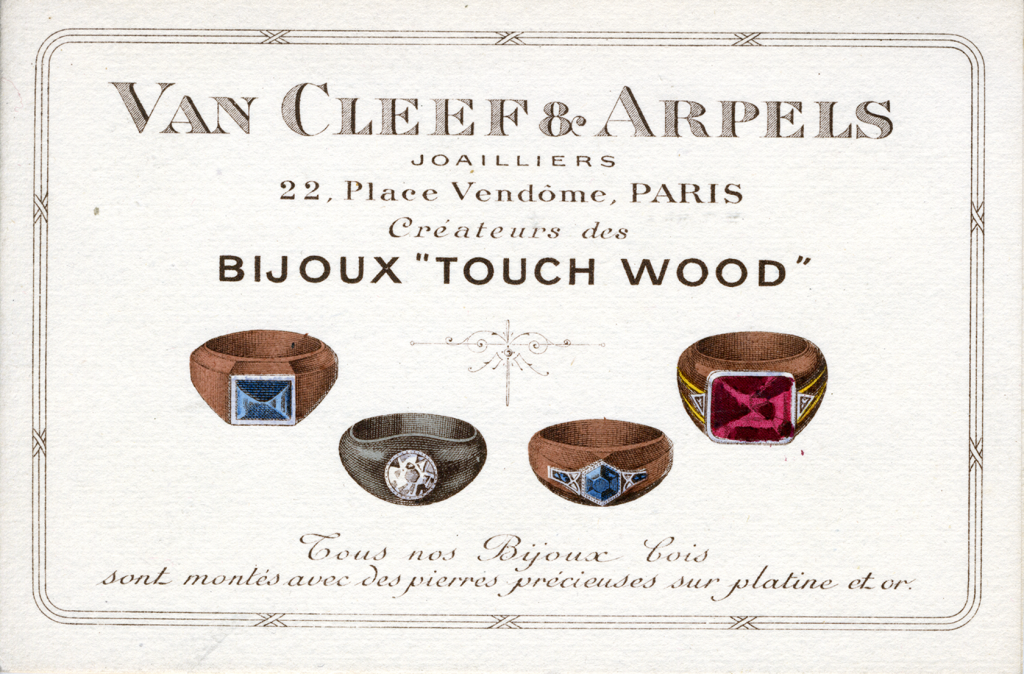

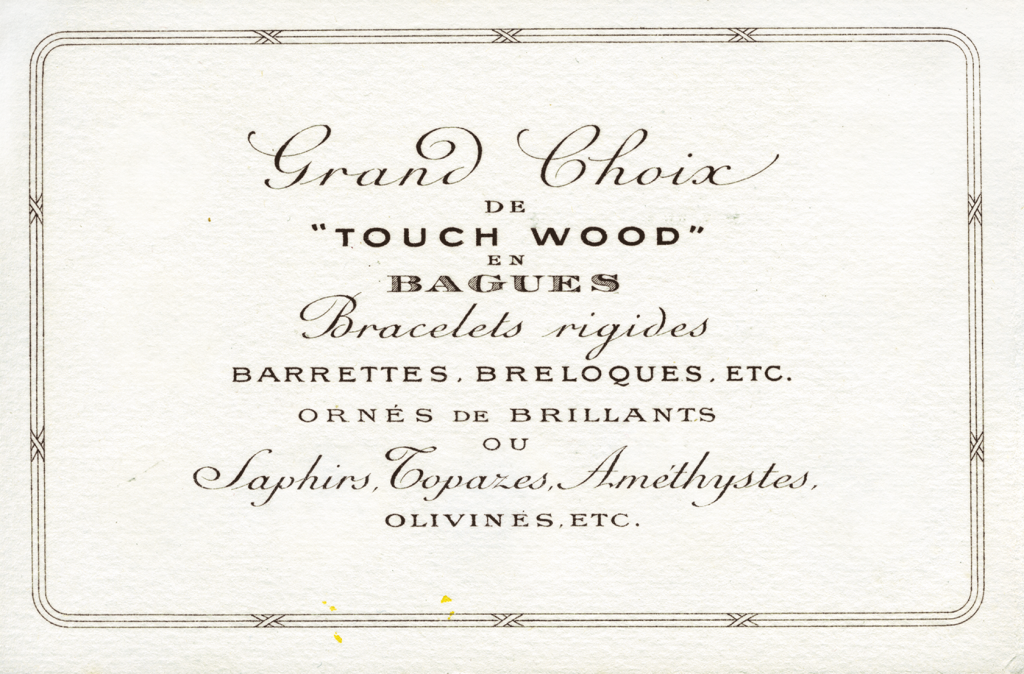

“Touch Wood” jewelry

The notion of investing jewelry with a talismanic value lay behind one of Van Cleef & Arpels’ first “successes,”4“Le Masque de Fer” (The Iron Mask), Le Figaro (July 10, 1916): n.p. the Touch Wood collection. This collection of wooden jewelry was named after the superstition whereby touching wood was meant “to thwart the vagaries of ill fortune,”5Le Figaro (December 22, 1916): n.p. and was marketed by the Maison from February 1916 to March 1920.6Stock book no. 2, pp. 72–73. Paris, Van Cleef & Arpels Archives. Our knowledge of the collection comes from documents in the Maison’s archives and from contemporary periodicals.

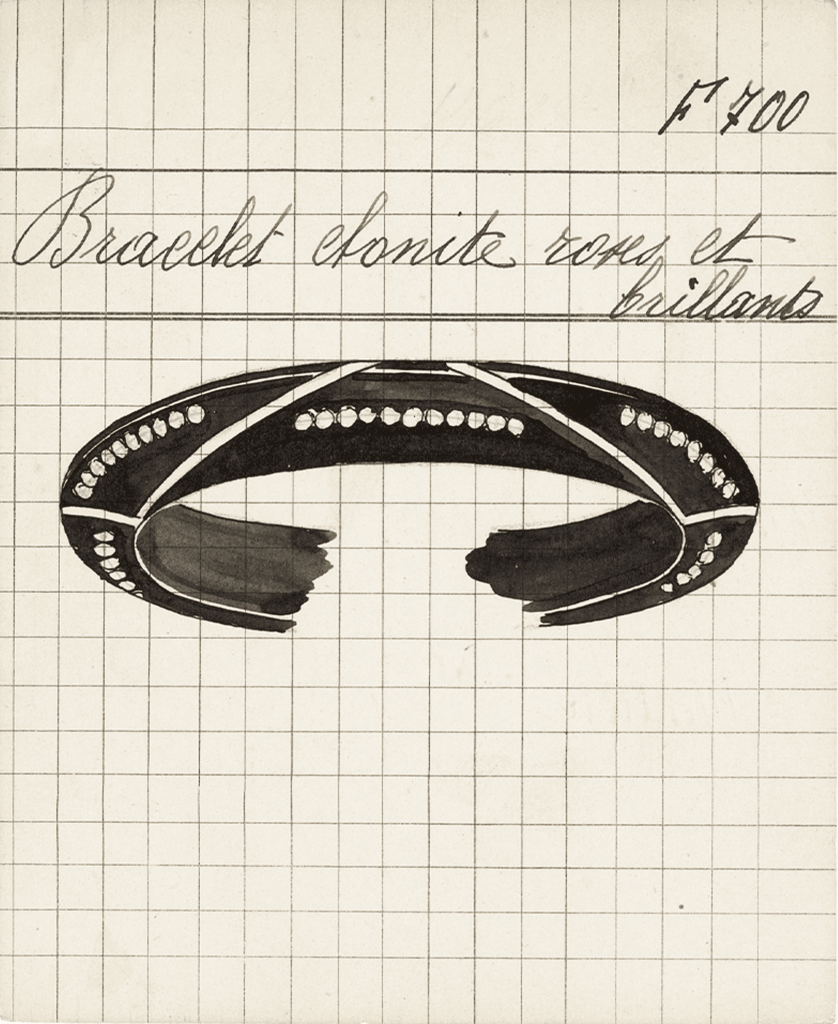

The product cards did not necessarily specify the species of wood used, although some did indicate the utilization of wood by-products like fibrite and ebonite.7Fibrite is a by-product of paper renowned for its resistance. Ebonite is a material characterized by its hardness. It is made of rubber to which a huge quantity of sulfur atoms are added. These materials, derived from the growing industrialization that had been aiding the jewelry arts since the previous century, sought to imitate precious woods like ebony and mahogany at considerably less cost. The product cards also tell us that these pieces of jewelry could be adorned with “platinum threads,” set with brilliant-cut, navette-cut, or rose-cut diamonds ; or even, for some models, sapphires, emeralds, rubies, topazes, amethysts, and olivines.

Wood was used for making both bracelets and rings, including wedding ones. The name Touch Wood was registered as a trademark on June 30, 1916. This step emphasized the Maison’s evident desire to create a coherent jewelry ensemble linked to the names Van Cleef and Arpels that would give it a distinctive creative identity. The press and advertising, in particular, played a major role in the recognition of this creativity. Journalists referred to an “artistic originality” on a number of occasions, and “the notion of joy that accompanied it.”8Anonymous, “Idées pour cadeaux d’étrennes,” Le Figaro (December 8, 1918): n.p.

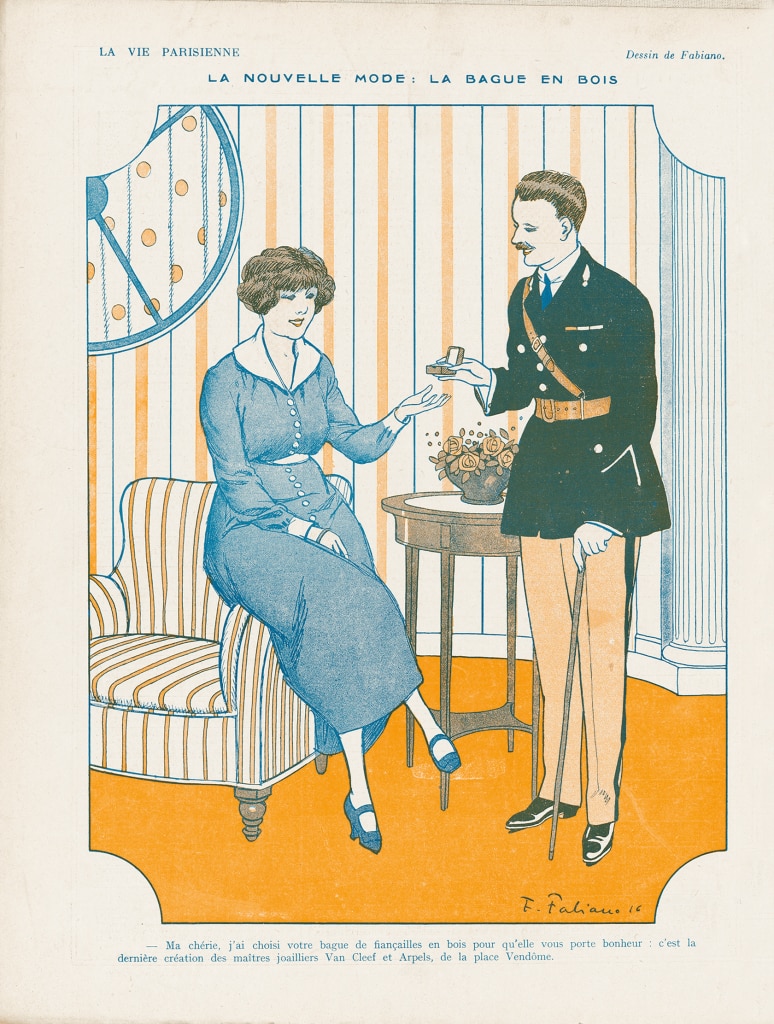

This notion of joy was all the more acclaimed for reflecting the wartime context that almost certainly lay behind the conception of this wooden jewelry: “The war godmothers of our infantrymen, assured by this new amulet, besieged the shop at Place Vendôme.”9P.R., Le Gaulois (June 13, 1916): n.p. The First World War aroused, at one and the same time, a patriotic emotion and “a feeling of piety”10Le Figaro (December 22, 1916): n.p. inspired by the hope of seeing the return of those men sent to the front. In fact, the period favored the revival of popular beliefs: “And here, in this grave moment we are living through, […] Van Cleef & Arpels have enabled us to satisfy [our] superstition, and in such a tasteful manner that everybody has become superstitious.” Advertisements showed soldiers on leave offering their fiancées a wooden ring that would bring them good luck.

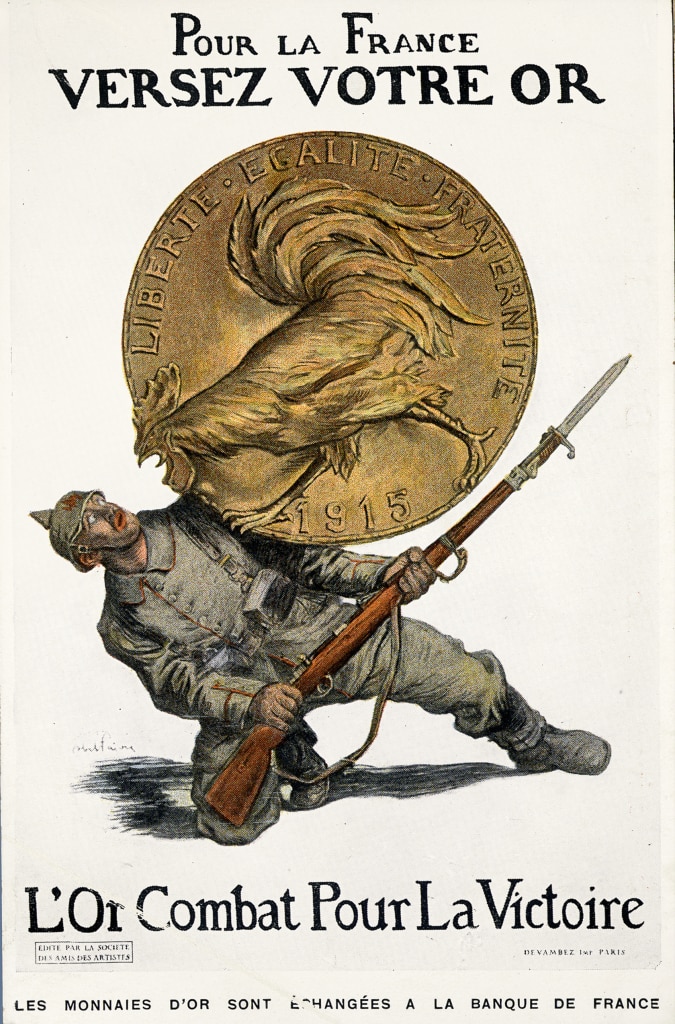

In return, the soldiers “adopted [these] lucky charms,”11Le Figaro (December 22, 1916): n.p. also in the form of a ring, that echoed the colors of the French flag by the addition of stones in symbolic tones: “Each of our ‘champions’ has his own lucky charm. He attributes his luck to this piece of jewelry […] adorned with a sapphire, a diamond, and a ruby that recall the noble colors for which he, the aviator, is risking his life.”12Le Figaro (December 22, 1916): n.p. The Touch Wood pieces, by using a less costly material than various metals or stones, also provided an answer to the French state’s repeated requisition of metal from 1915 : “At the present time, when precious metals must be reserved for the good of the nation, the sole and legitimate way of touching a French heart is “to make an arrow with any wood.””13Le Figaro (December 22, 1916): n.p.

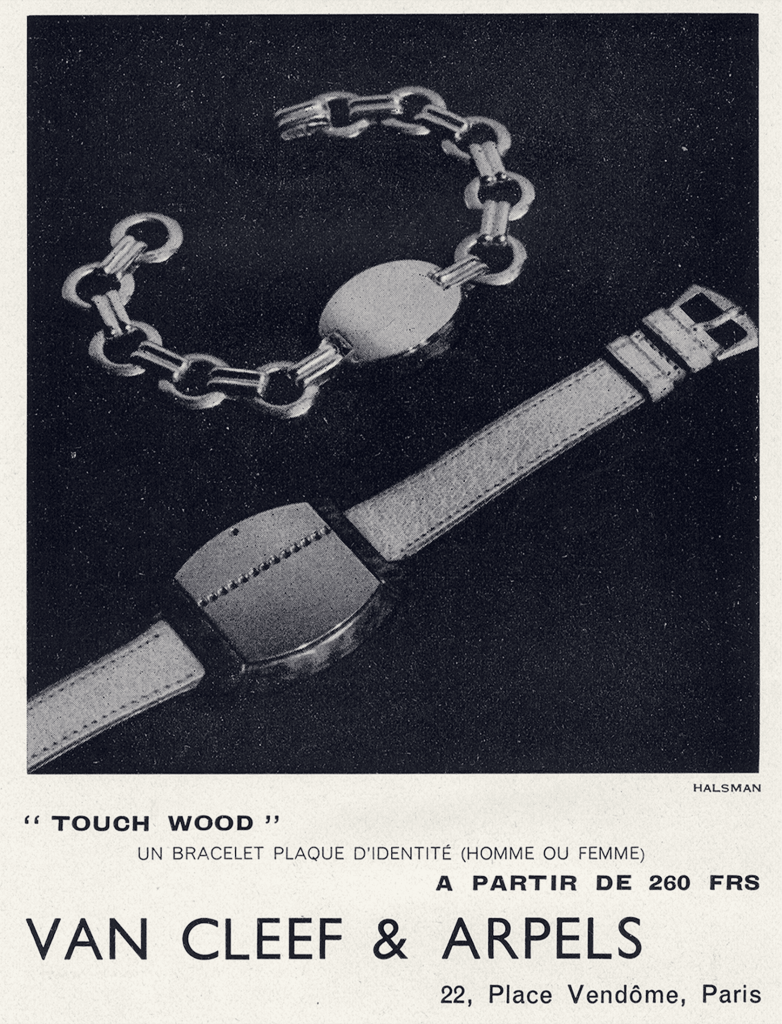

These wooden pieces also served as a counterpoint, in terms of material economy, to the “aluminum rings”14Le Figaro (December 22, 1916): n.p. sent from the trenches. Their apparent simplicity15Le Figaro (December 22, 1916): n.p. and discretion16Le Gaulois (December 4, 1916): n.p. made them all the more popular, for they corresponded to the austerity of the time. It was equally significant to note a return to the Touch Wood production on the eve of the Second World War. During the latter half of 1939, Van Cleef & Arpels introduced a variant, the wooden ID tag.17Le Figaro (October 14, 1939): n.p. The Touch Wood jewelry produced in 1940, unlike that made during the First World War, was very quickly taken up by men for the most part. These “new good-luck charms”18Le Figaro (October 14, 1939): n.p. designed by the Maison were hugely successful between January and February 1940, once again “protecting” French soldiers.

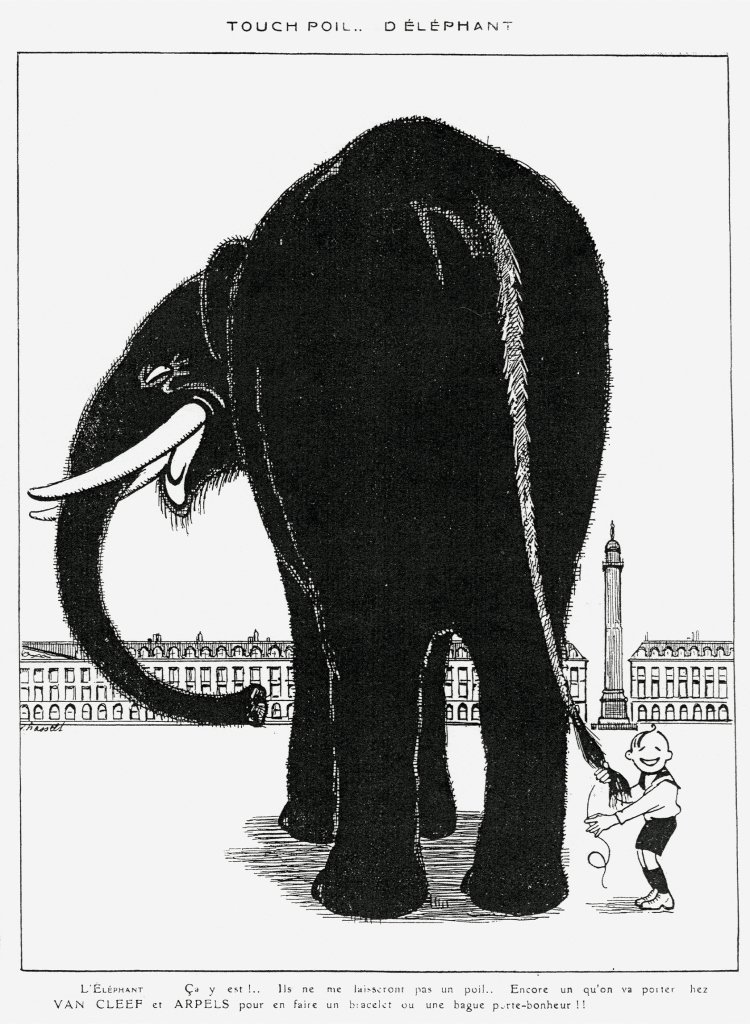

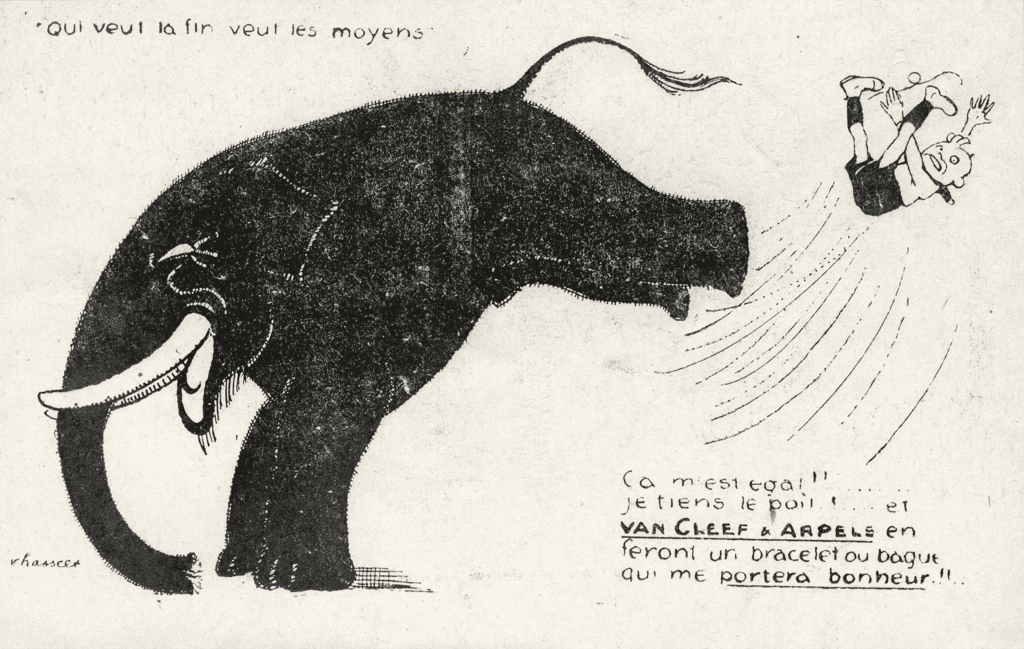

Jewelry made from elephant hair

In addition to wood, other materials were used for creating talismanic jewelry. The taste for organic materials such as shagreen, ivory, and tortoiseshell, that was found throughout the decorative arts at this time was echoed in a series of rings and bracelets made of elephant hair, produced by the Maison in 1918. The rings were mounted on platinum, while the bracelets were adorned with a platinum clasp set with brilliant-cut and rose-cut diamonds, or a gold and enamel identity tag, or a white diamond jewelry ribbon.

As with the Touch Wood jewelry, advertisements linked these pieces to the quasi-frenetic quest for talismanic objects during the First World War, while adopting a humorous tone. The press told of a soldier who, having “worn a Touch-wood […] adorned with gemstones around his wrist,” and attached “a medallion containing [a] precious four-leafed clover […] to the chain of his watch,” and even “had some gris-gris or blessed amulets sent [from Senegal],”19André Alexandre, “Un guignard,” La Baïonnette (July 4, 1918): 426. “had paid a fortune to bribe a guardian in the Jardin des Plantes to procure some elephant hair” to have a jewelry talisman made from it.

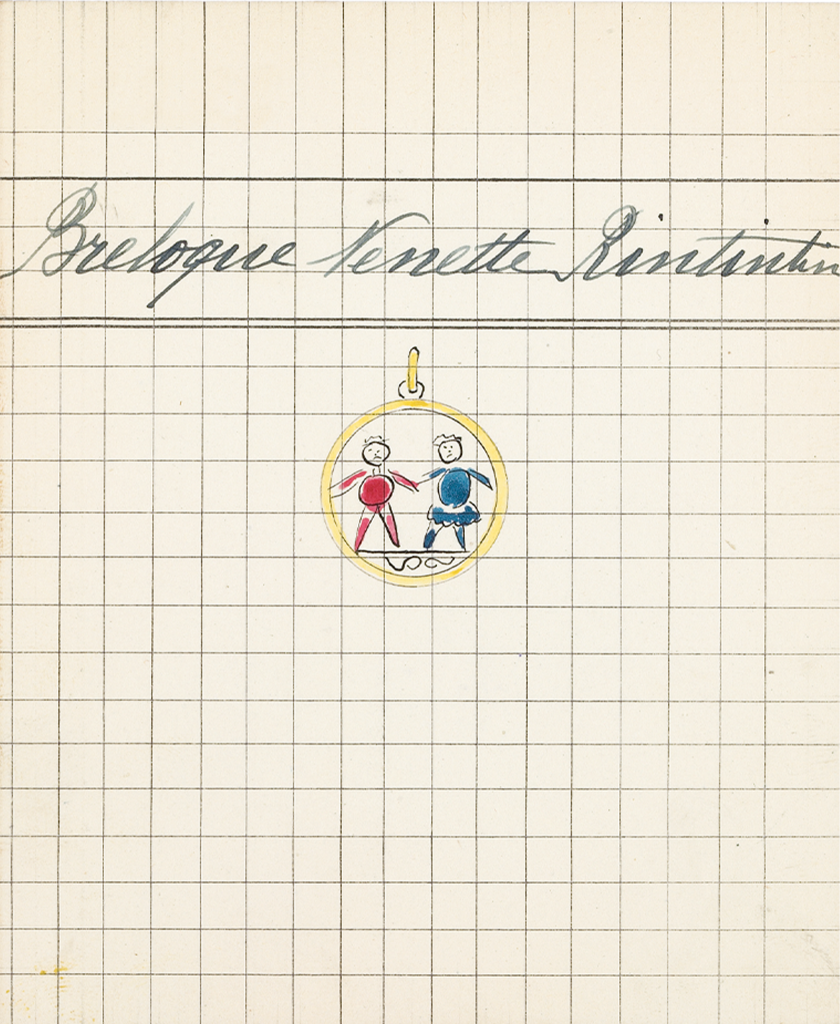

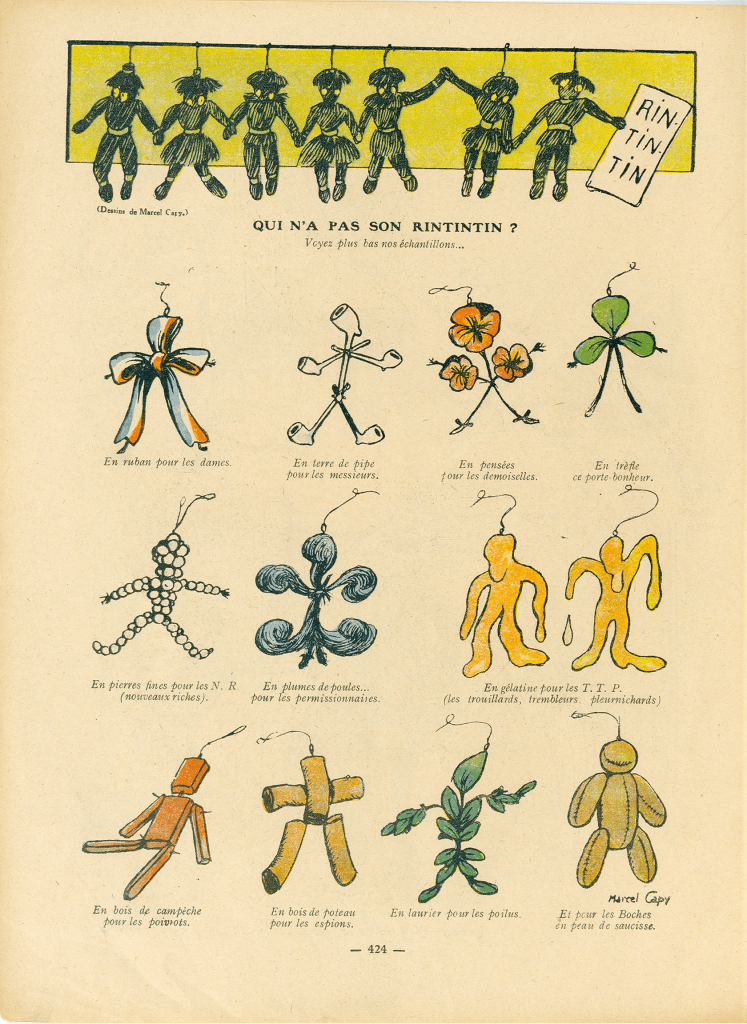

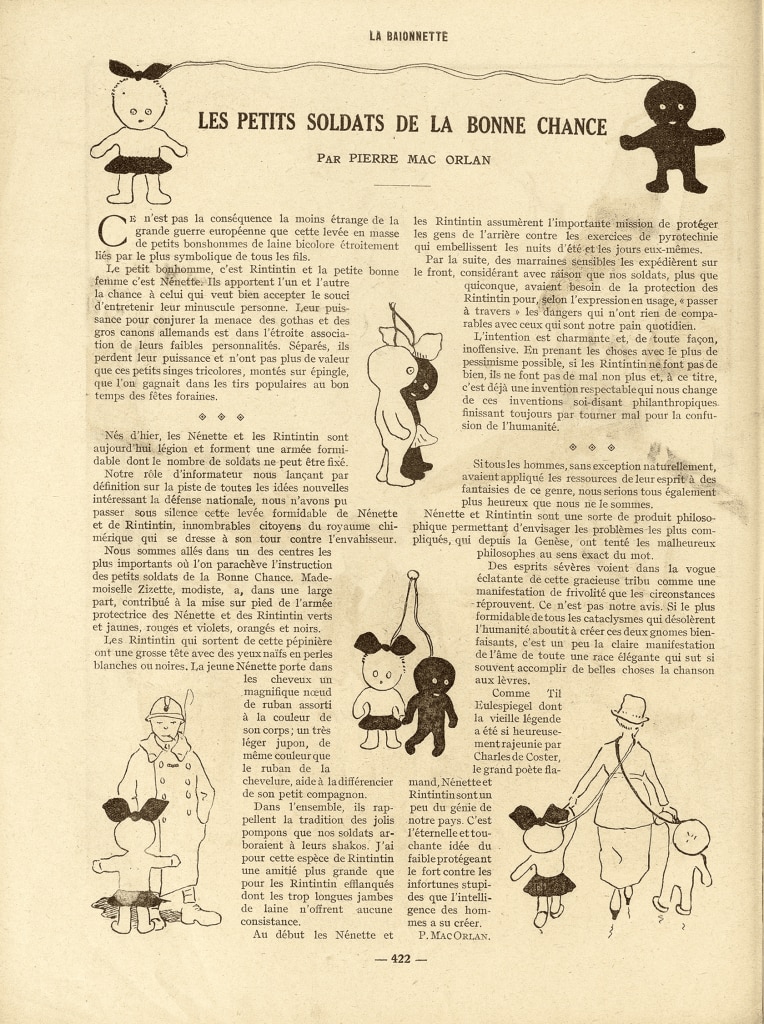

Nénette and Rintintin

Van Cleef & Arpels gave shape to this superstitious sentiment that was widely shared by the French people during the First World War, with the production of charm bracelets featuring distinctive iconography. These charms were made at the very end of the War, in August 1918, and represented two characters, one male, the other female, in red and blue enamel respectively, standing within a yellow gold circle. These figures feature in one of the Maison’s product cards under the names “Nénette and Rintintin.”

They were invented by Francisque Poulbot and were originally porcelain dolls sold by Les Grands Magasins du Louvre and La Samaritaine department stores from Christmas 1913. They then became lucky charms made of wool, linked to one another by a thread, which were hugely popular for the duration of the War.

These “little soldiers of good fortune”20Pierre Mac Orlan, “Les Petits Soldats de la bonne chance,” La Baïonnette, no. 157 (July 4, 1918): 422. were “[attached] to [a] buttonhole, [a] jacket, [and] the rims [of] hats.”21André Alexandre, “Un guignard,” La Baïonnette (July 4, 1918): 426. At first, they were taken up by “those behind the lines”22Pierre Mac Orlan, “Les Petits Soldats de la bonne chance,” La Baïonnette, no. 157 (July 4, 1918): 422. who contributed to the war effort, such as the “women making shells, […] typists, and […] women knitting sweaters.”23Georges Delaw, “Nénette et Rintintin,” La Baïonnette (July 4, 1918): 420. Gradually, however, they reached the front: “Compassionate war godmothers sent them […] reckoning, quite rightly, that our soldiers, more than anyone else, needed the protection of the Rintintins to ‘pass through the dangers,’ as the expression of the time put it.”24André Alexandre, “Un guignard,” La Baïonnette (July 4, 1918): 426. Van Cleef & Arpels produced a version of this “gris-gris” that was less easily destroyed, replacing the wool threads with yellow gold and enamel. The Nénette and Rintintin medallion was threaded on an elephant-hair bracelet, thereby duplicating its talismanic advantages.

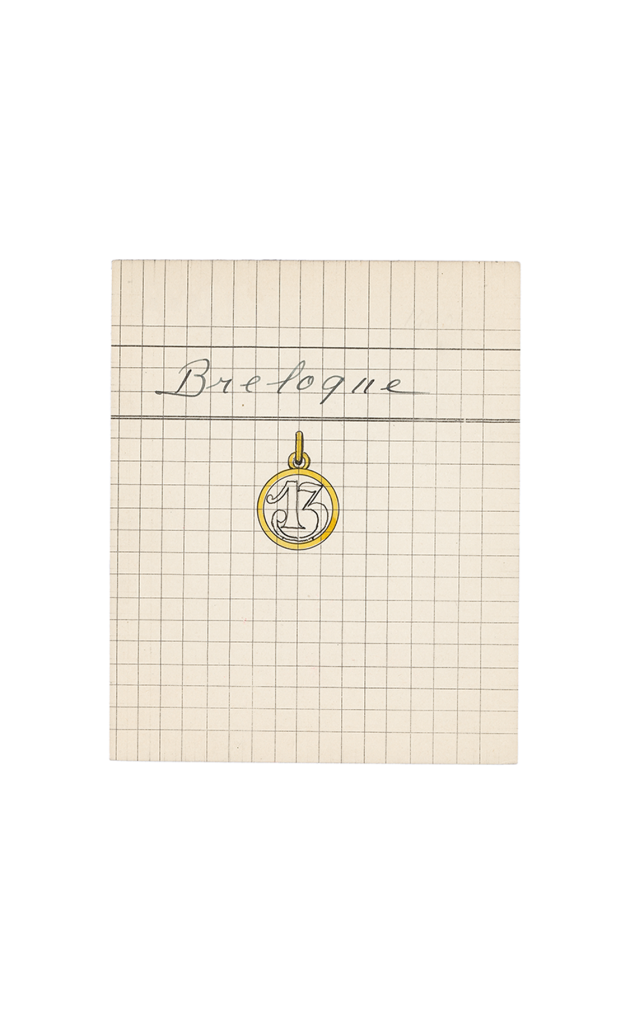

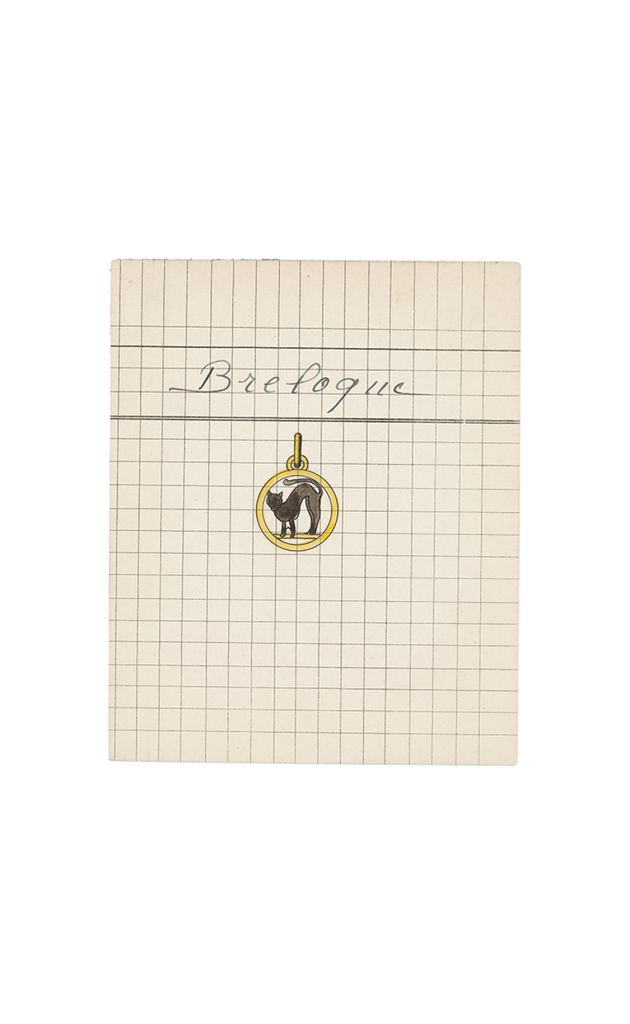

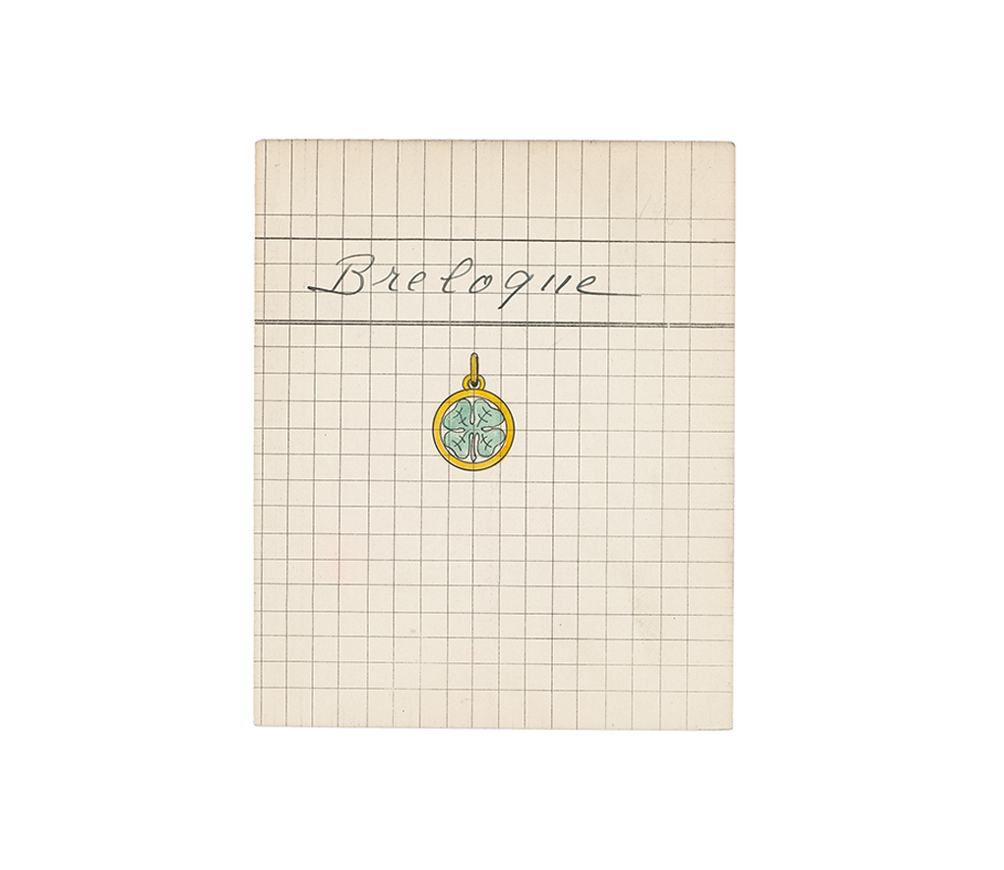

Charms— pendants attached in quantity to bracelets— were often associated with good-luck iconography. They were produced in great quantity during the First World War, as they were small in size, often made of enamel, therefore not too flashy and less expensive. Many jewelers, including Van Cleef & Arpels, created charms in the shape of medals, with a four-leafed clover in the middle, or the number thirteen or even a black cat.

GOOD-LUCK CHARMS

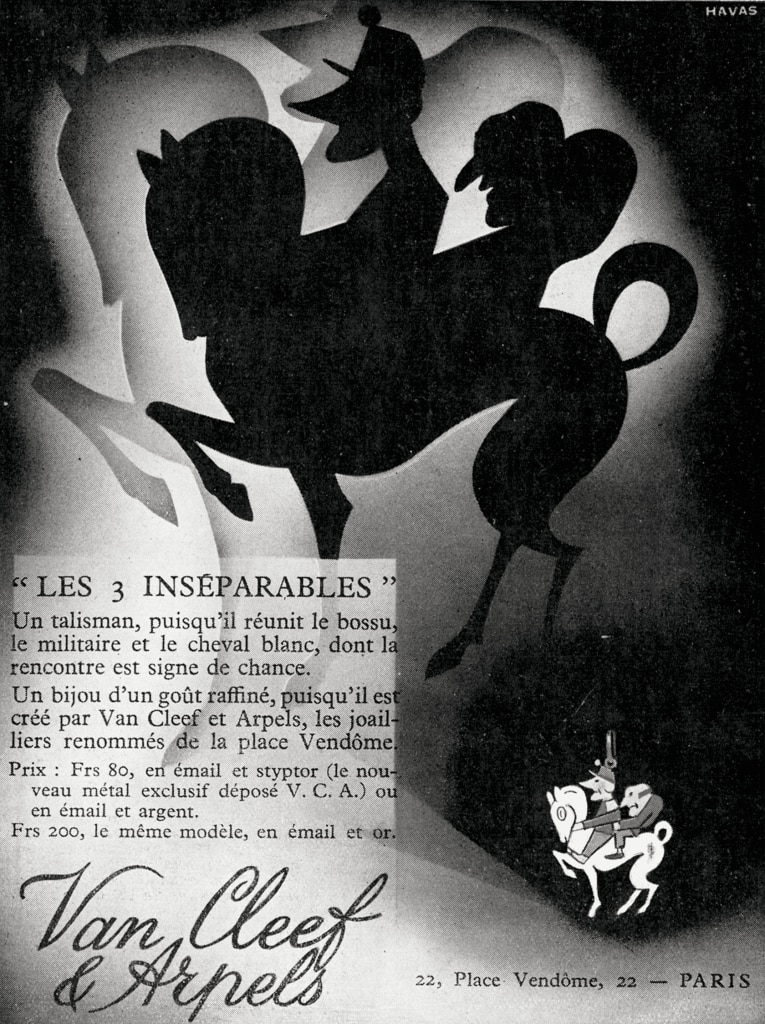

The three inseparables

The popularity of good-luck jewelry lasted beyond the War. The above-mentioned charms, for instance, were still available until 1925, after which Van Cleef & Arpels developed new models and renewed the iconographic lexicon. From the end of 1932, for example, three figures in colored lacquer contained within a yellow gold disc, appeared on the styptor clasp system of a purse. The encounter of these “three inseparables”—a hunchback, a soldier, and a white horse—ensured “[success] in these initiatives,”25Van Cleef & Arpels advertisement, L’Illustration (February 25, 1933). according to the Maison’s advertisement. Inspired by a Parisian adage—“on the Pont-Neuf, you’ll always encounter a soldier, a white horse, and a hunchback”26Anonymous, “Variétés,” Journal de Toulouse politique et littéraire (March 6, 1859): n.p. This adage almost certainly referred to the wide range of people who rubbed shoulders on the Pont-Neuf: “The Pont-Neuf was the general meeting place for strollers, […] beggars, the rich, […] pick-pockets, […] the middle classes, valets, pages, gentlemen, soldiers, monks, […] women, […] acrobats, street performers.”—this trinity had been considered auspicious since the nineteenth century. There was renewed interest in this popular belief in the 1910s,27Paul-Yves Sébillot, “LVI Rencontres,” Revue des traditions populaires (September 1912): 431. which was to “give birth, [in the early 1930s], [to a] lucky charm that is seen nowadays in the [Van Cleef & Arpels] shops.”28L’Intransigeant (July 11, 1933): 2.

The image was initially characterized by its geometric stylization, later becoming more simplified. This trinity appeared on various supports; clips, which could be used as clasps for purses, gave way in 1933 to a brooch, then a cap for an automobile radiator, and finally a charm. The latter was the one produced the most by the Maison because “addressed to [its all] elegant clientele.”29Anonymous, “Le Super Porte-Bonheur 1933,” Excelsior (December 30, 1932): 2.

Two enameled versions were commercialized, one in styptor or silver, the other, more costly, mounted on yellow gold. The success of the Three Inseparables charm was supported by the press who named it the “Good-luck charm [of the year] 1933.” 30Anonymous, “Le Super Porte-Bonheur 1933,” Excelsior (December 30, 1932): 2.

The iconography of games of chance

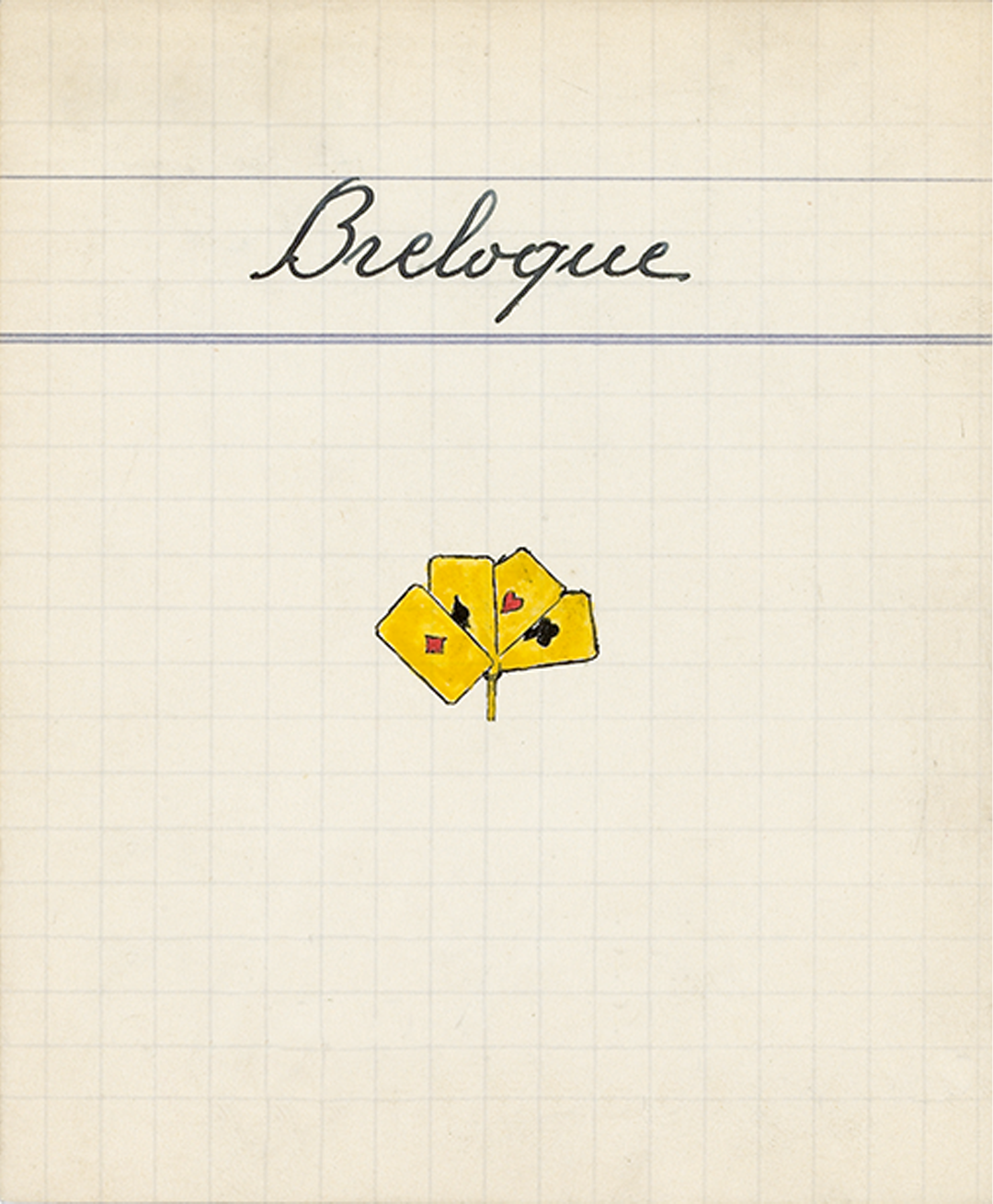

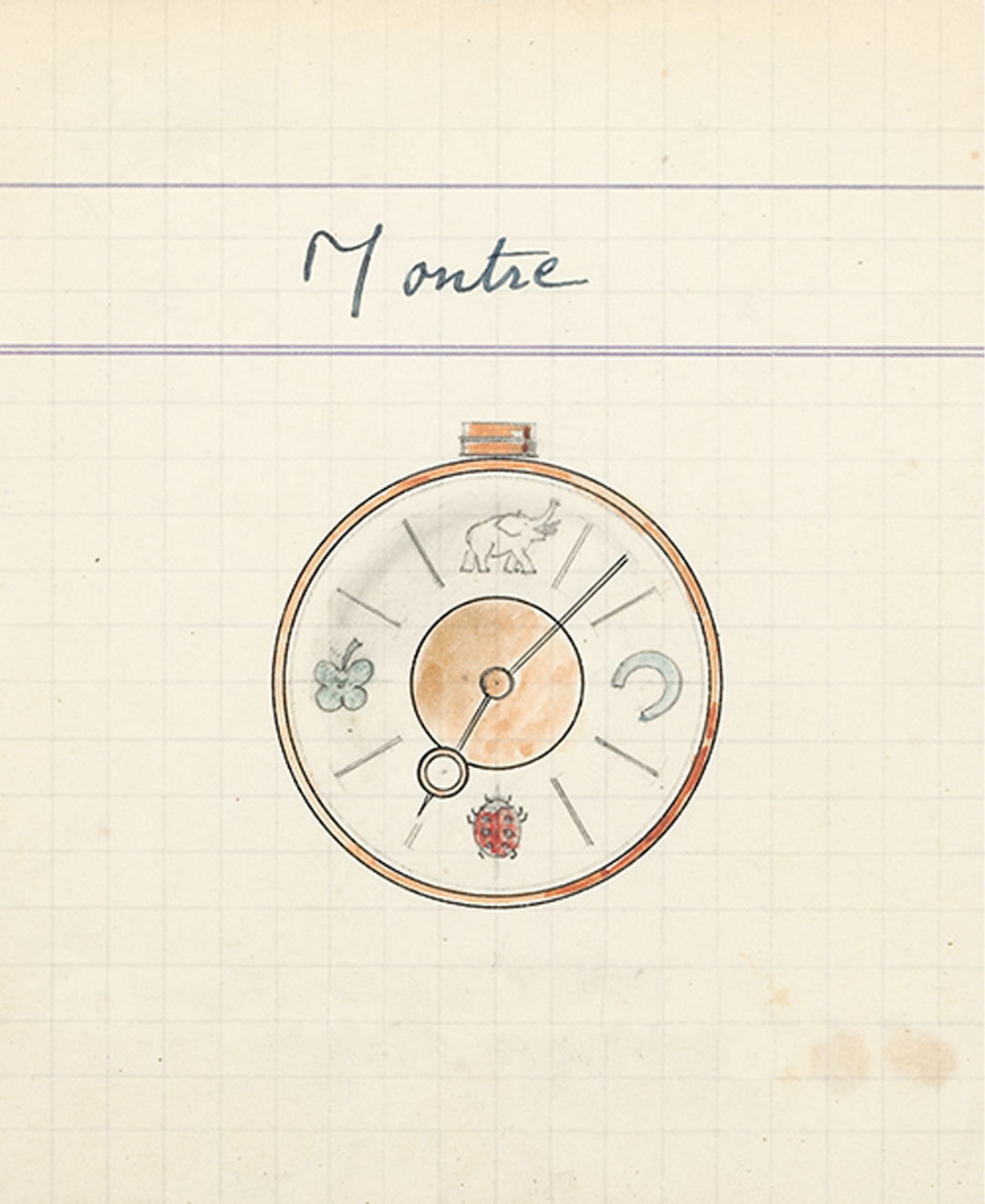

Van Cleef & Arpels also borrowed from the iconography of games of chance for its creation of different objects evoking good luck. In 1933, for example, a charm composed of the four aces of a pack of cards was made in enameled yellow gold for a model known as “Plein aux as” [French term literally meaning “quad aces,” but really meaning “flush” or “rolling in money”]. A number of creations featured a roulette wheel. The first of these was a literal transcription with the roulette wheel figuring on the lid of a cigarette box dating from 1926. The red and black “pockets” made of enamel stand out against the white gold surround while the arrow is fixed to a guilloché yellow gold “cone” . The whole piece is framed by a pattern of red and black lines. In 1937, the standard numbering of a roulette wheel was replaced by four lucky charms—a horseshoe, a ladybird, a four-leafed clover, and an elephant—painted on the case of a pocket watch. Lastly, in a 1959 advertisement extolling the merits of a medal-style charm, we see a roulette wheel edged with ruby and turquoise cabochons. In the middle is a yellow gold daisy with the words of the popular counting rhyme surrounding it: “I love you / a little / passionately / madly / not at all” [similar to the English one: “She loves you, she loves you not”].

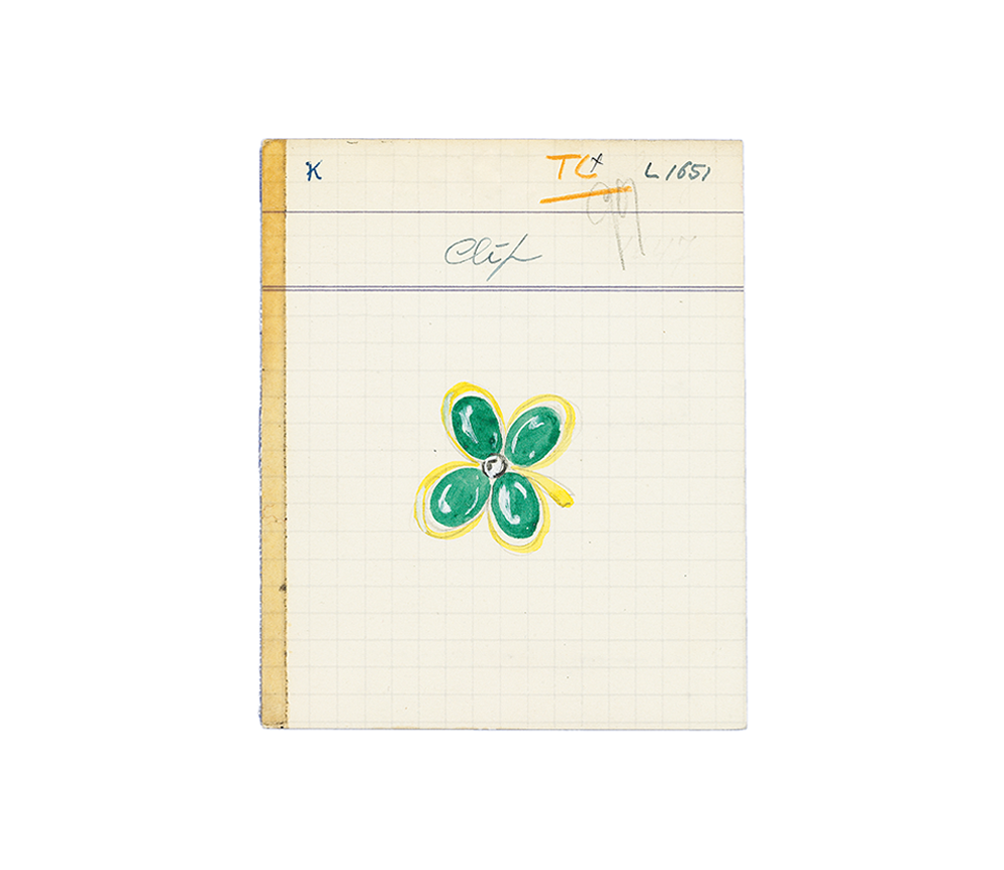

From clover clips to the Alhambra long necklace

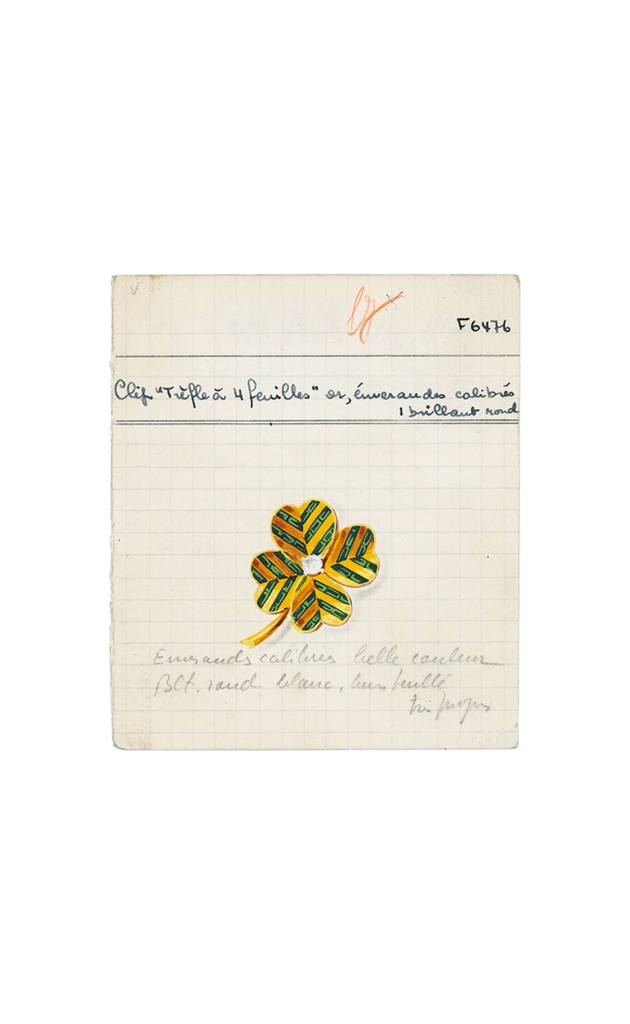

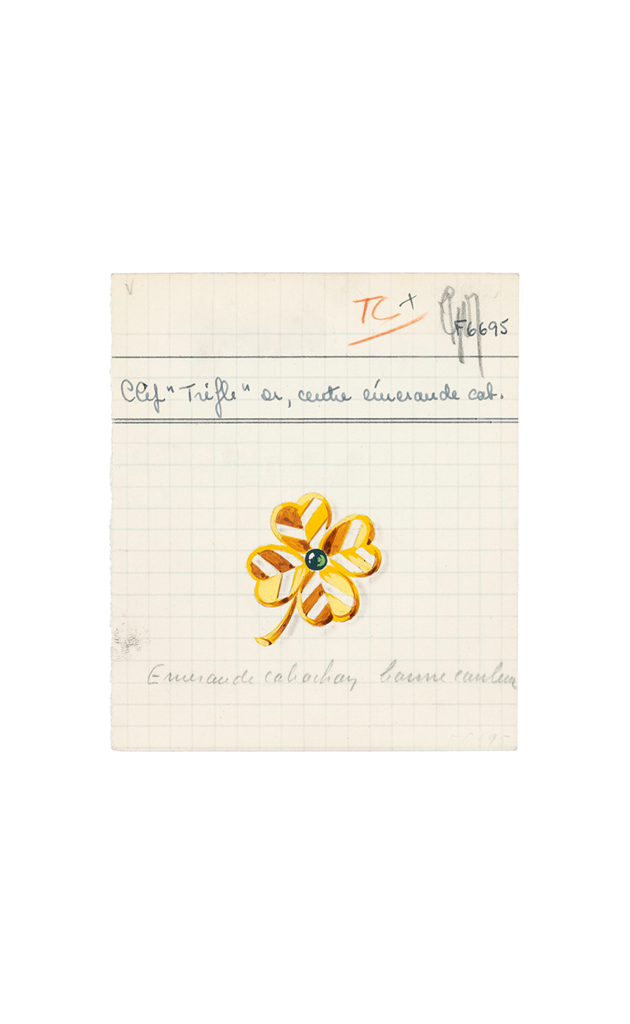

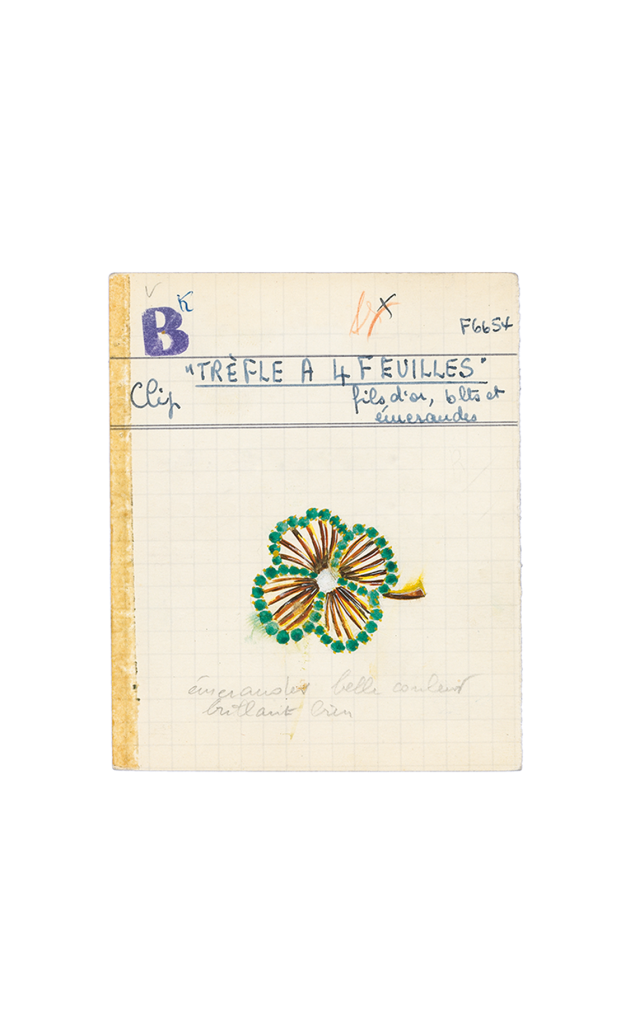

The four-leafed clover, which appears in the Maison’s archives as early as 1906, became the most frequently seen good-luck motif from the 1950s onward. The first of these, at the start of the decade, was a clip with four leaves of emerald cabochons framed by yellow gold. A few years later, in 1954, Van Cleef & Arpels began developing a whole series of small, clover-shaped clips. Their leaves, alternately openwork and solid yellow gold, were arranged around an emerald. One model had alternate rows of yellow gold and calibrated emeralds for its leaves, with a diamond at its center. In 1960, the rays of yellow gold used for the Whirl series and the tutus of the Dancer clips were adapted for the clover leaves to give them volume. The four leaves were edged with small round emeralds, evoking the color of the plant.

CLOVER CLIPS

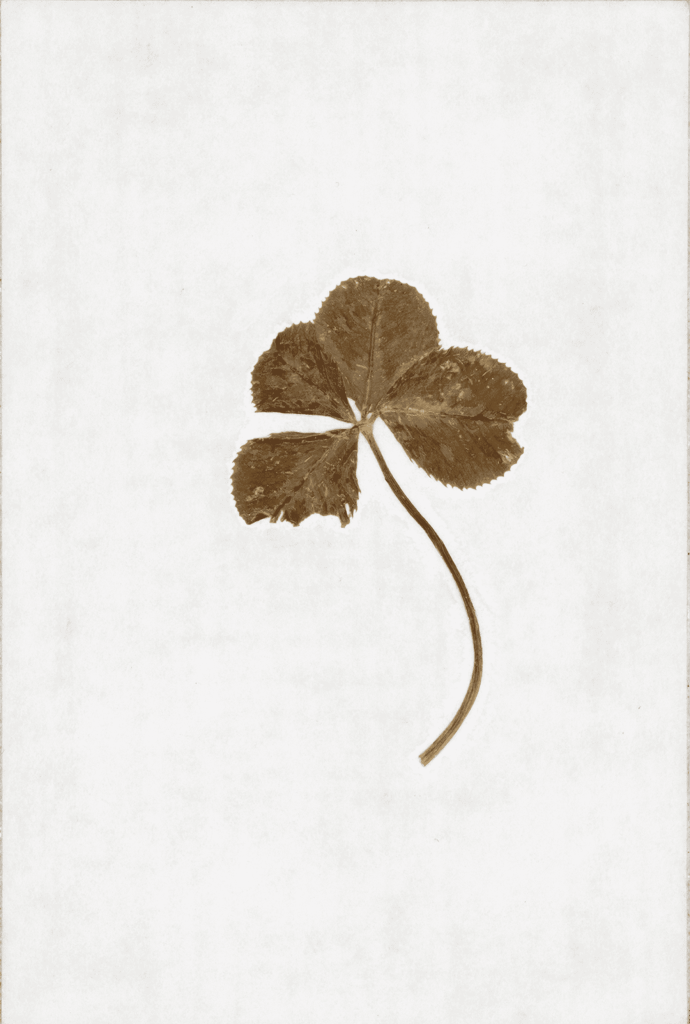

Further proof of the Maison’s partiality for this motif is seen in the card that Jacques Arpels offered to its members with a pressed four-leafed clover on it. This charming pressed-plant image underlines the importance of this motif, reproduced on numerous clips.

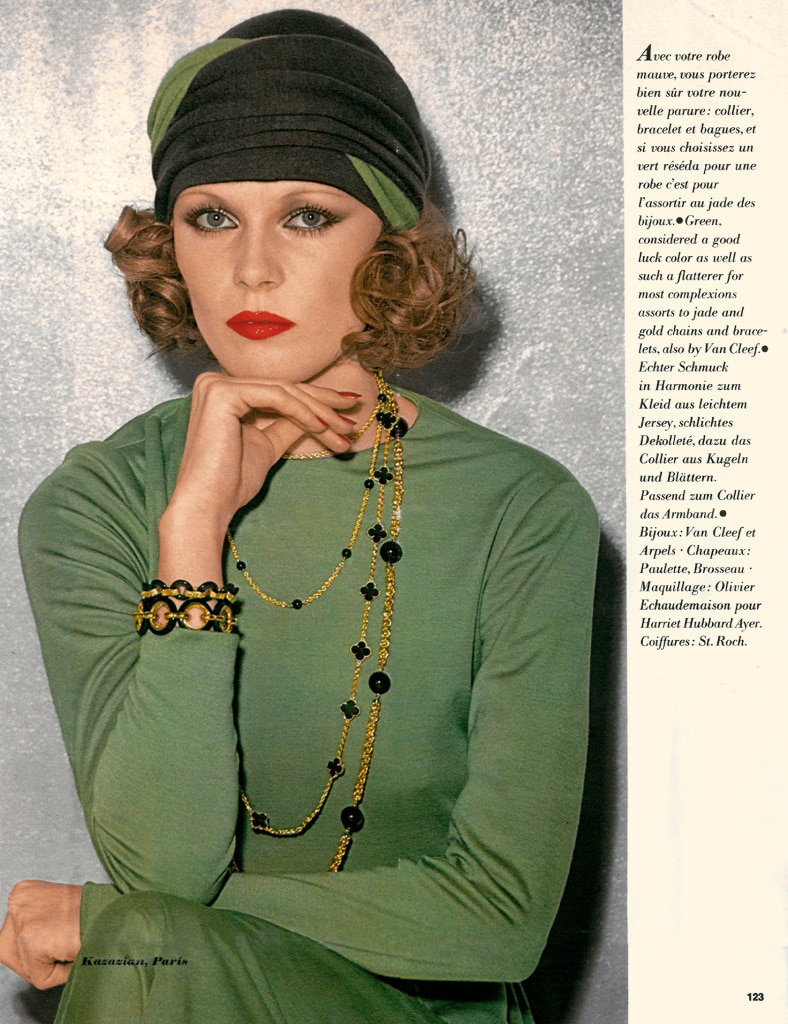

A decade or so later, when good-luck jewelry was right back in favor, the ever-popular four-leafed clover gave rise, in 1968, to one of the Maison’s greatest successes, the Alhambra long necklace. The association of this original model with a simplified plant silhouette was supported by a major publicity campaign.31See: Femme, no. 2, 1979. La Mode chic, no. 47, 1974; Van Cleef & Arpels advertisement, Connaissance des arts (June 1974).

The Alhambra motif was created in a wide range of colors thanks to the use of ornamental stones, including green—the color of good luck32Élégance, no. 63, 1974, p. 123.—as in malachite and agate. The Alhambra creations were modern good-luck pieces aimed at a new generation, that could be worn over “a dress or [with] jeans.”

The return of the wooden jewelry in the 1970s and 1980s

The 1970s saw a revival of jewelry made from elephant hair and from precious wood, most frequently snakewood or amboyna. The elephant-hair pieces were distinguished from those made in the 1910s by their proportions. The Siam bracelet, for example, made in 1973, consisted of circular rows of elephant hair with four quadrangular motifs in textured yellow gold placed at the cardinal points. As for the wooden pieces, their success was once again due to the popular belief associated with them. It was Jacques Arpels who was largely responsible for their reissue. He had the habit of saying that “to be lucky, you have to believe in luck,” and this statement even featured on one of the new models of wooden bracelets.

The wooden jewelry made during the 1970s was distinguished by its diversity of form; Domino watches, pens, Bow clips, and Nerval earrings adopted the name “Touch Wood”, while the good-luck charm became a pendant. The symbol of good luck, a four-leafed clover, here in yellow gold, was added to this use of wood. Surrounding it, in yellow gold, was the inscription “I will bring you good fortune.” Over and above its decorative purpose, there- fore, we can see that jewelry, when endowed with symbolism, illustrates the fears, expectations, and longings of society. Its iconographic motifs, developments, appearances, and disap- pearances attest to the aspirations of the people of its time.