In the aftermath of the 1925 Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes, Van Cleef & Arpels pursued its commercial and creative development. The Maison, however, lost one of the key figures responsible for this expansion, Émile Puissant, who died in 19261Anonymous, “Le Monde et la ville,” Le Figaro (February 22, 1926): 2..

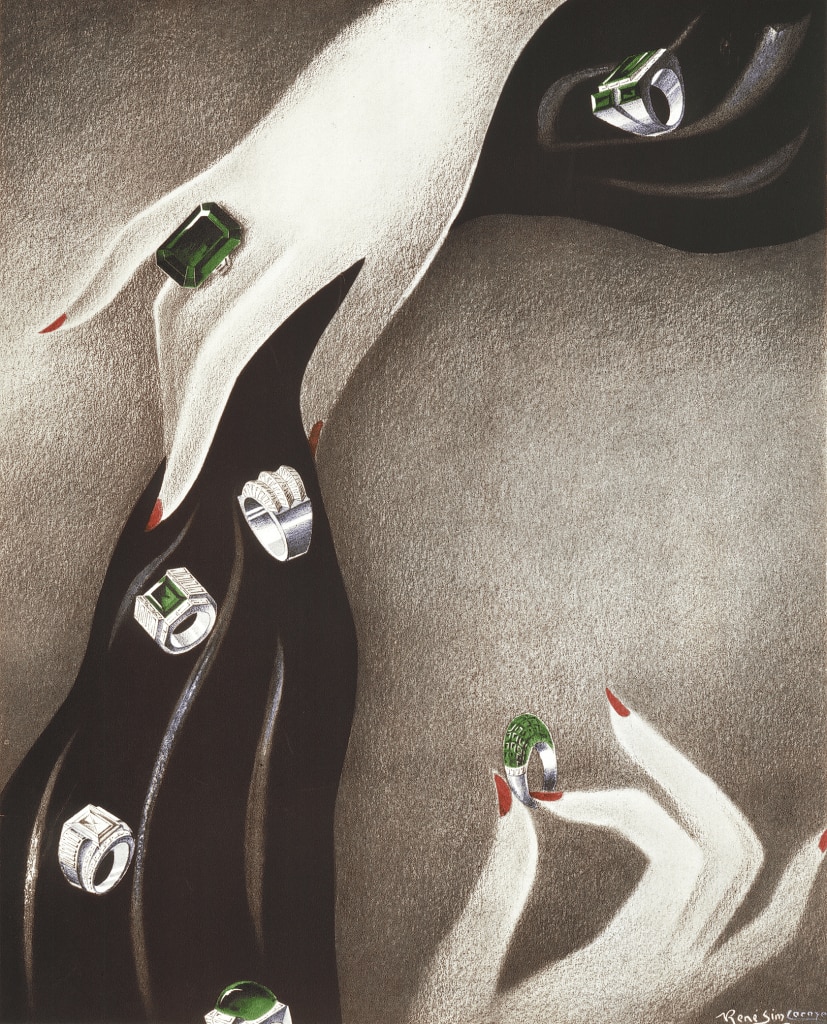

His wife, Renée Puissant, took over as Artistic Director of the Maison2René Sim Lacaze, “Ce siècle avait un an,” [s.l.] (1994): 74., continuing her husband’s work alongside René Sim Lacaze.

Renée Puissant and René Sim Lacaze, a creative duo

They were both responsible for the creative galvanization that constituted Van Cleef & Arpels’ esthetic identity between 1926 and the build-up to the Second World War. As René Sim Lacaze pointed out: “My close collaboration with Madame Puissant worked wonders; she readily admitted that she could not draw.”3René Sim Lacaze, “Ce siècle avait un an,” [s.l.] (1994): 74. While it appeared that René Sim Lacaze oversaw the stylistic unity of the Maison’s designs, Renée Puissant was almost certainly active in selecting the projects put forward by the designer-producers working for the company.

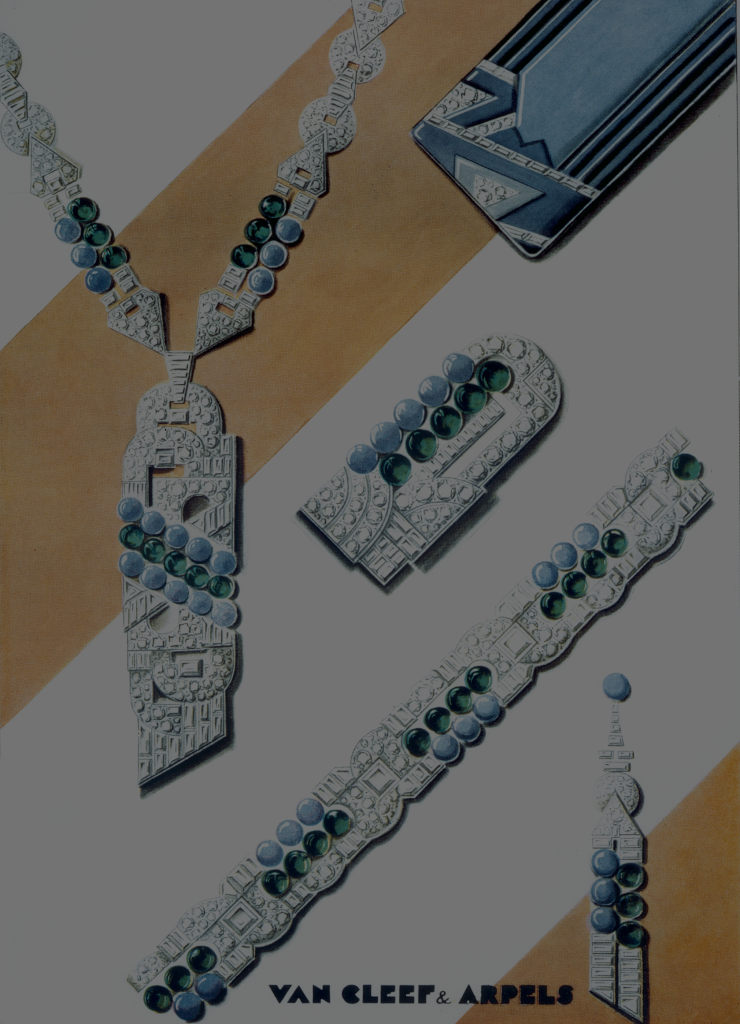

The early years of this creative duo were marked by preparations for another exhibition, this time entirely dedicated to jewelry and gold- and silverwork, to be held at Palais Galliera in 1929. In order to achieve the same success as in 1925, the Maison turned to two workshops: Rubel with whom it had worked on the jewelry that was awarded the Grand Prix at the 1925 Exposition des arts décoratifs, and Sellier-Dumont.4For further information on this workshop, see: Rémi Verlet, Dictionnaire des joailliers, bijoutiers et orfèvres en France de 1850 à nos jours (Paris: Gallimard, 2022), 2085–2086.

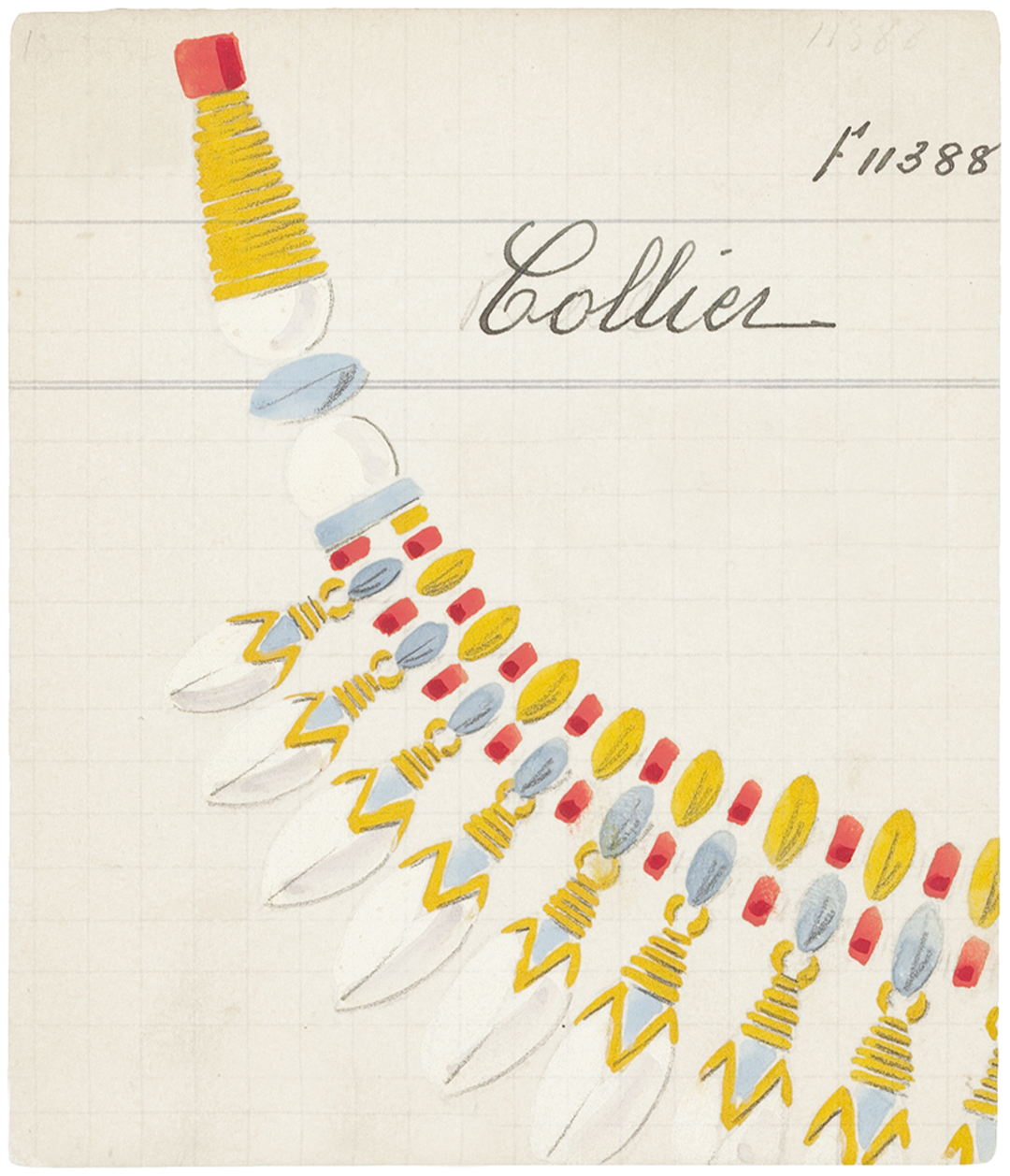

These collaborative ventures resulted in novel jewelry forms welcomed by the press, like tie-necklaces, long necklaces forming straps or converted into bracelets, short necklaces in the shape of textile collars or that came apart to form a pendant and brooch. All these pieces were made of platinum and diamonds, with a colored stone—sapphire, emerald, ruby or turquoise—demonstrating an opulence rarely seen in the Maison’s work until then.

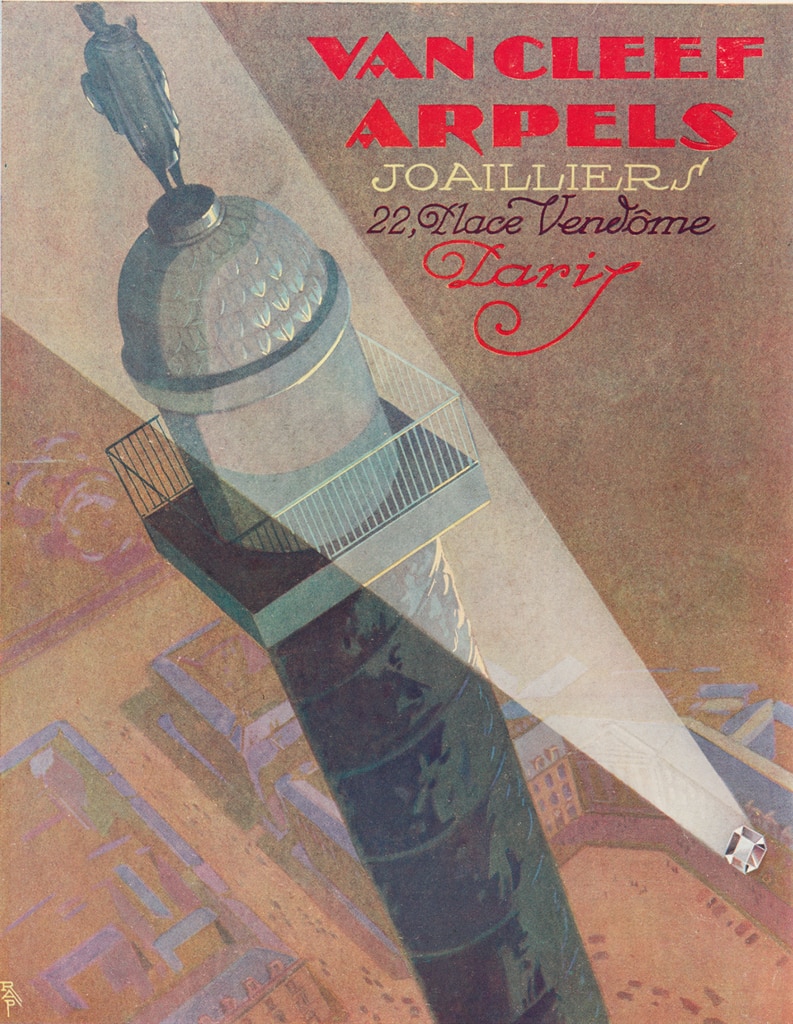

Vendôme Column, the Maison new identity

The desire to create a unique identity was also seen in the Maison’s search for a logo. In 1928, a competition was jointly organized by Van Cleef & Arpels and the review La Renaissance de l’art français et des industries de luxe “for an advertising design […] that could be adapted to all of Van Cleef et Arpels’ printed material.” “More than a thousand entries were placed before the jury” and “the Vendôme Column […] [is] repeated in a hundred different forms, some more original than others.”5Henri Clouzot, “Le Concours Van Cleef & Arpels,” La Renaissance de l’art français et des industries du luxe, (January 1928): 479. [Bilingual French-English publication.] From then on, this iconography increasingly featured in the advertisements produced by Van Cleef & Arpels, promoting the link between the famous column and the Maison, and confirming Place Vendôme as the center of French jewelry.

Opening of the New York shop

Other members of the firm took charge of the development of the business and the introduction of Van Cleef & Arpels into new markets. Jules Arpels, in particular, who was “reputed to be an excellent salesman,”6René Sim Lacaze, “Ce siècle avait un an,” [s.l.] (1994): 92. was one of the instigators behind the opening of a New York branch. Since the beginning of the century, the major jewelry houses in Paris had understood the importance of having an office, if not a shop, on the other side of the Atlantic, given the sheer number of American clients frequenting their premises in Place Vendôme or Rue de la Paix.

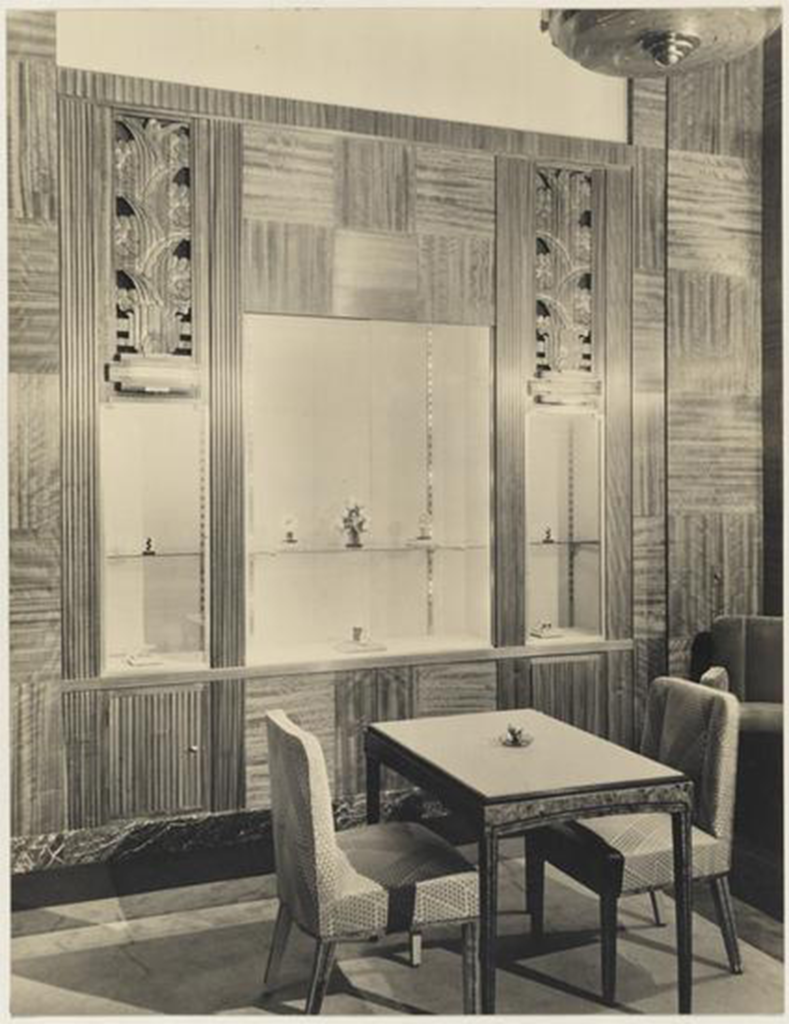

The location of the shop was chosen in early 19297Anonymous, “Rent Fifth Avenue Space,” The New York Times (February 3, 1929): 50. and the boutique at 671 Fifth Avenue was inaugurated in October8Anonymous, “Van Cleef & Arpels, Inc., to Close,” The New York Times (April 30, 1931): 41. of that same year9Memorandum addressed to Leidesdorf & Co., September 17, 1946, Van Cleef & Arpels Archives, New York.. This new premises was characterized by its relative “simplicity,” suited to “a luxurious atmosphere.”10Anonymous, “Glass, Wood and Metal,” Vogue (January 1930): 73.. The New York boutique opted for the “skyscraper”11A design esthetic inspired by European Art Deco, characterized by architectural volumes and the omnipresence of straight lines, echoing the developments in architecture throughout America’s large cities. See: Christopher Long, Paul T. Frankl and Modern American Design (London: Yale University Press, 2007). look developed in the United States while remaining close to the Art Deco style in vogue in Paris at that time. The Maison called upon the American architect Ely Kahn to design the interiors composed of a “main sales room and a more private reception room”12A design esthetic inspired by European Art Deco, characterized by architectural volumes and the omnipresence of straight lines, echoing the developments in architecture throughout America’s large cities. See: Christopher Long, Paul T. Frankl and Modern American Design (London: Yale University Press, 2007). “The severity of the walnut wall panels” in the former and Walter Kantack’s glass and metal lighting “was balanced by the grey-beige and lavender rugs and furnishings.”13A design esthetic inspired by European Art Deco, characterized by architectural volumes and the omnipresence of straight lines, echoing the developments in architecture throughout America’s large cities. See: Christopher Long, Paul T. Frankl and Modern American Design (London: Yale University Press, 2007).

The opening of this branch soon bore fruit. The visibility of Van Cleef & Arpels in the American editions of magazines such as Vogue was considerably enhanced after 1929.

When recession leads to innovation

Just a few days after the inauguration of the New York shop, the Wall Street Crash occurred on October 24, 1929. While the economic repercussions were not immediate, they nonetheless underpinned the closure of the Van Cleef & Arpels, Inc. shop a while later, in 193114Anonymous, “Van Cleef & Arpels, Inc., to Close.”. The parent company back in France also suffered the consequences of the American crisis, the value of its shares downgraded every year between 1930 and 1935 and divided by forty15Procès-verbaux de l’assemblée générale de la société Van Cleef & Arpels (Minutes of the general assembly of the Van Cleef & Arpels company), 1930–1935, Van Cleef & Arpels Archives, Paris..

The consequences were also visible in the stock held by the Maison. The ostentatious jewelry sets created for the 1929 Exposition International were taken to pieces, the stones removed from their mounts and the platinum melted down. The recession forced jewelers, especially Van Cleef & Arpels, to turn to less costly materials. This material constraint obliged the Maison to become ever more innovative, in line with the stylistic evolutions occurring within the decorative arts in the late 1920s. In 1929, the Union des Artistes Modernes was founded by a group of artists, interior designers, architects, and jewelers in reaction to the traditionalism of the Société des Artistes Décorateurs.

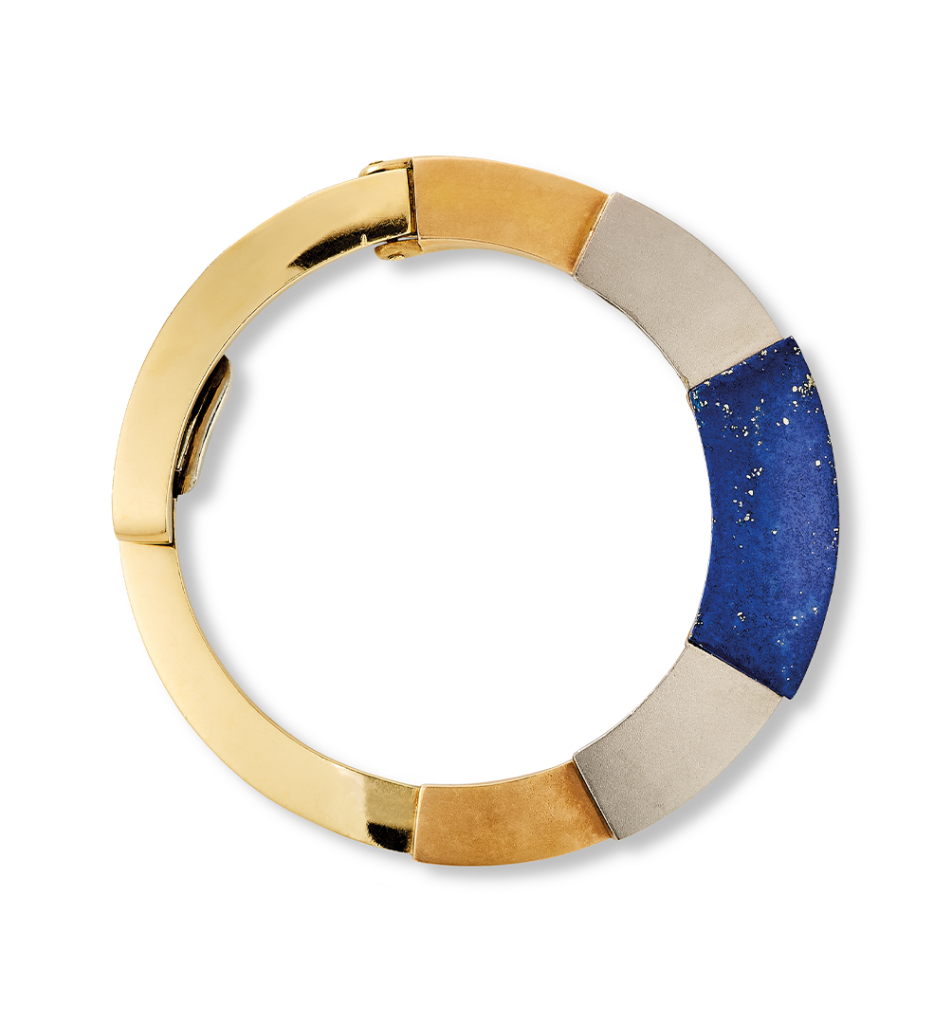

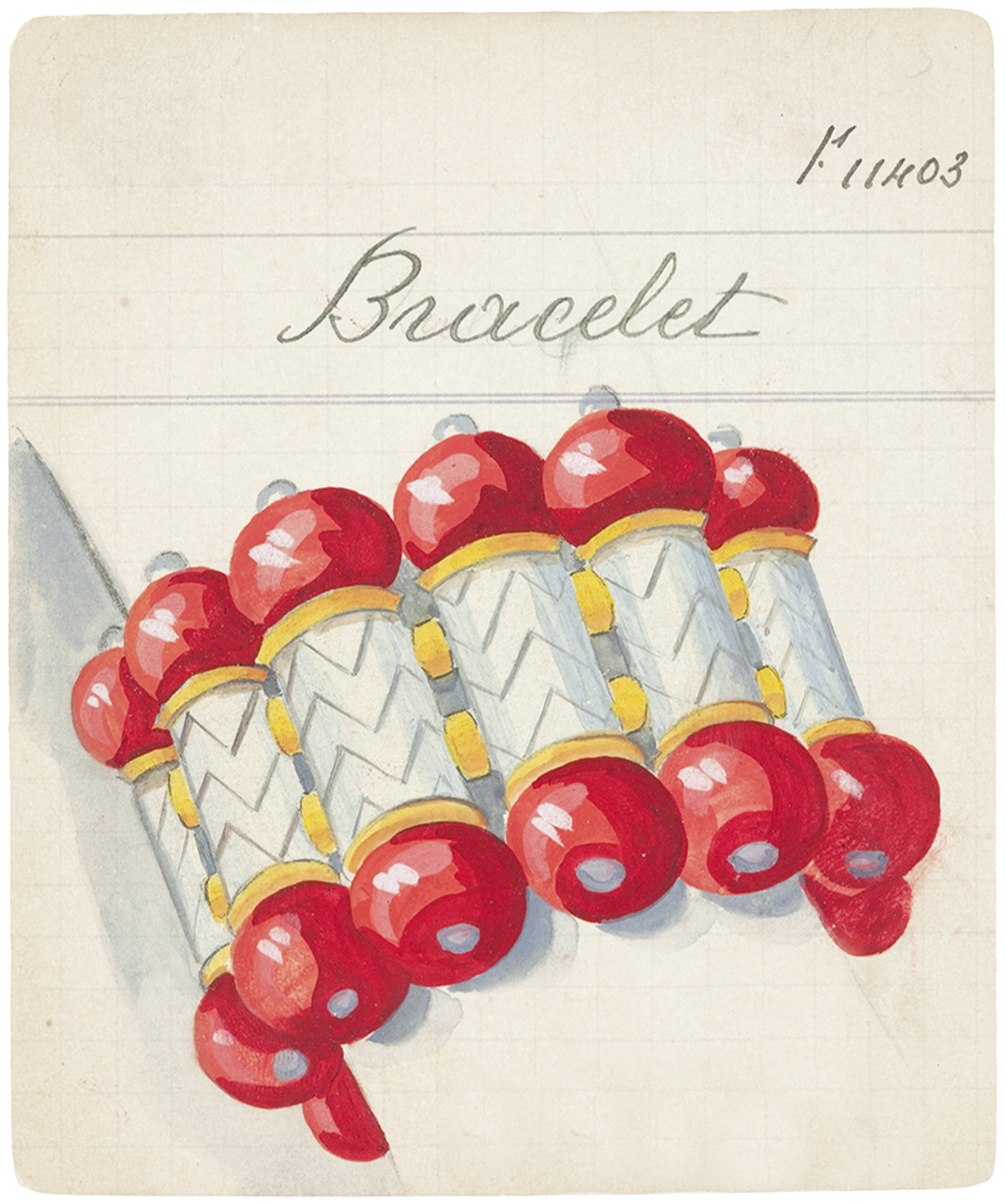

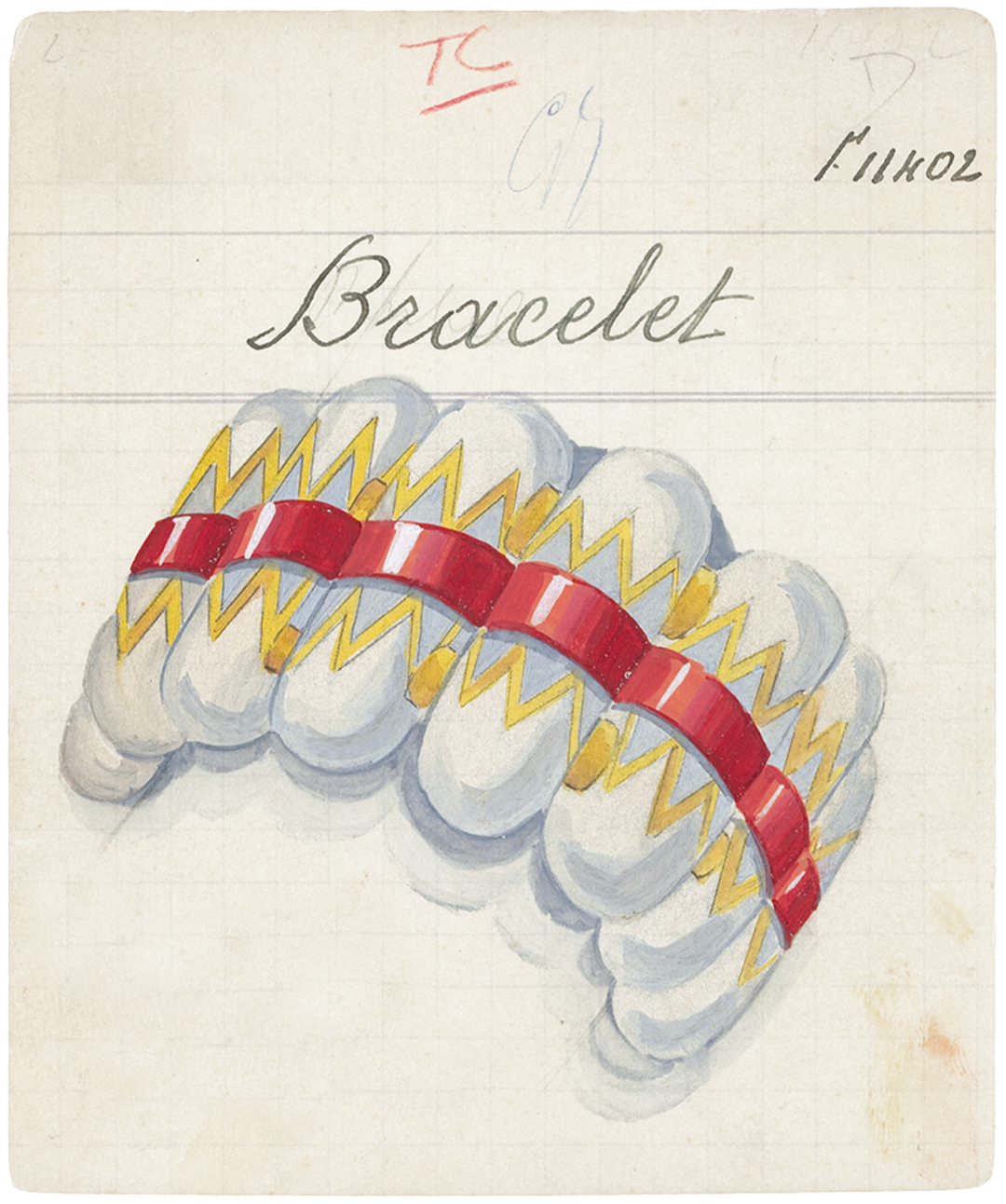

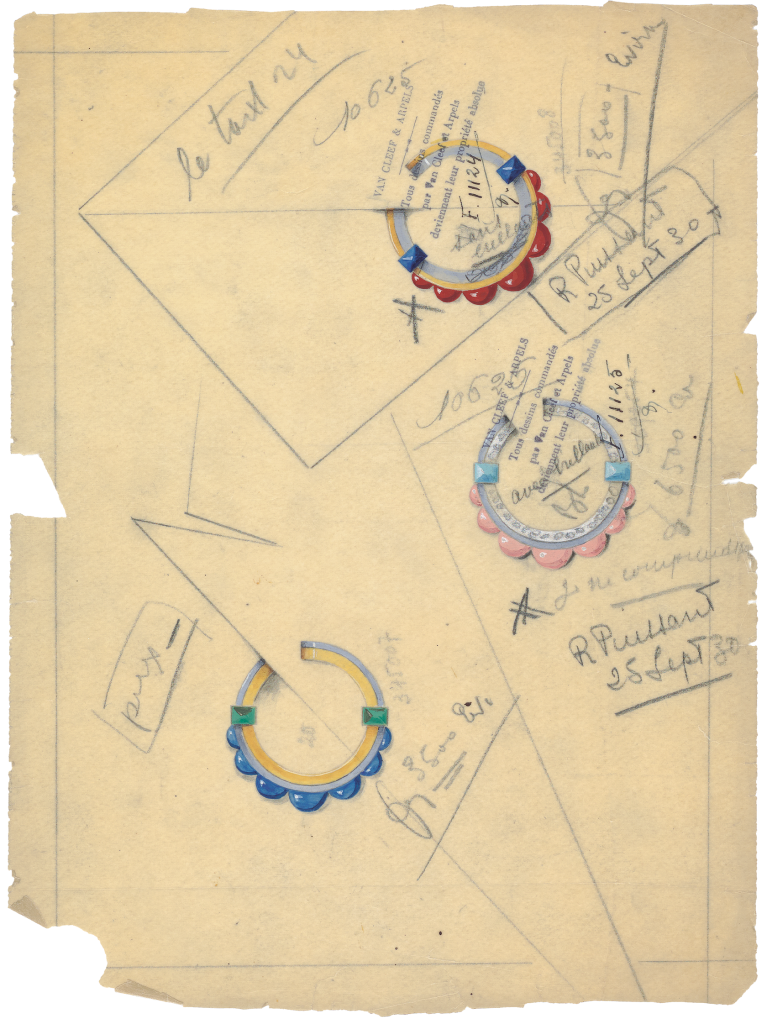

The Maison developed new jewelry models, no doubt at the instigation of Renée Puissant and thanks to the savoir-faire of the Rubel, Sellier-Dumont and Verger Frères workshops. These models, which were novel both stylistically and technically, notably included objets d’art, timepieces, clasps for purses, and so-called “fantasy” jewelry. They formed a coherent group defined by decorative sparsity and a wide color palette that used ornamental stones such as lapis lazuli, coral, turquoise, chalcedony, and malachite, and various metal alloys, yellow and pink gold, plator and osmior. These gemstones and metals, although generally considered less precious than diamonds and platinum, almost certainly owed their popularity to their stylistic originality as much as to the economic conditions of the time.

Despite the latter, an innovative form, the Circle brooch, was created exclusively16Recueil de la Gazette des tribunaux : journal de jurisprudence et des débats judiciaires (1937): 359-360. for the Maison as part of its production for the year 1930. This brooch, with its novel fastening system, was produced as a series—the model was no longer a one-off piece but rather, was produced in a variety of ways.

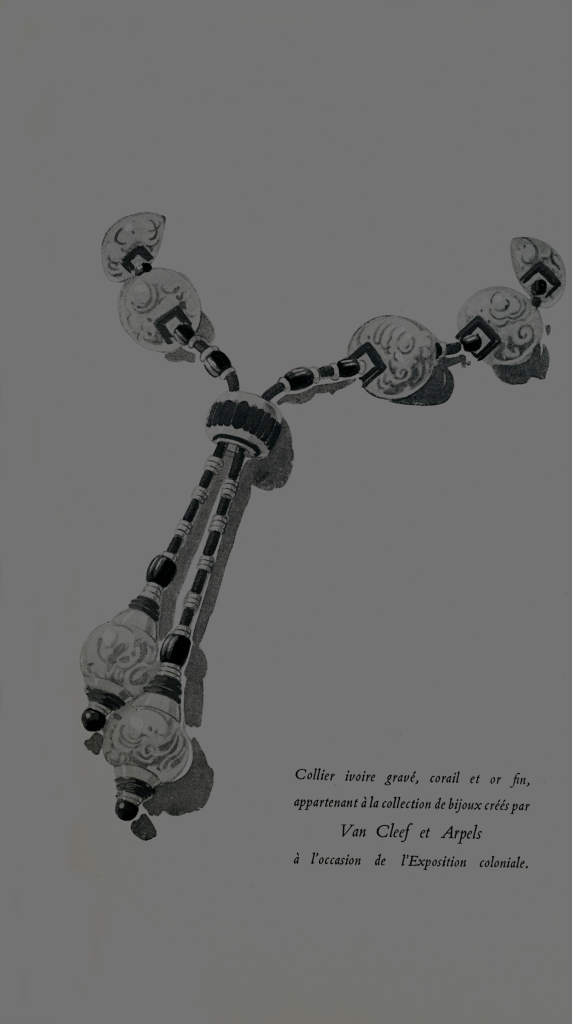

This exploration of materials reached its apex in 1931, with the Exposition Coloniale in Paris. African art and, to a lesser extent, Asian art, provided “fantasy” jewelry with new materials and decorative languages: “[Van Cleef & Arpels] borrowed from the Orient and created a necklace, earrings, and a ring composed of yellow gold disks, as pointed as Chinese hats.” The Maison was also noted for another “equally first-rate necklace […] encircling the neck with pear-shaped ivory pendants, like dragon’s teeth.”17Anonymous, “Paris Jewellery,” Vogue (September 1931): 66.

A unique creative dynamism

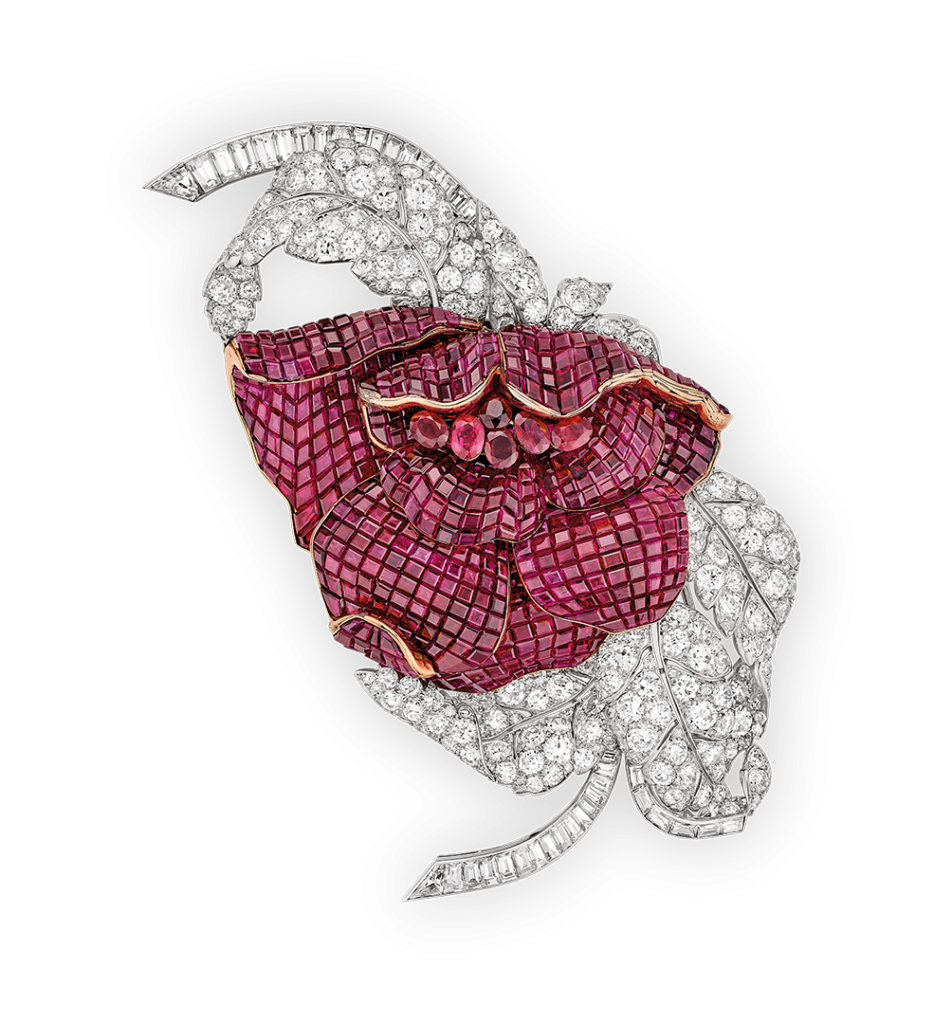

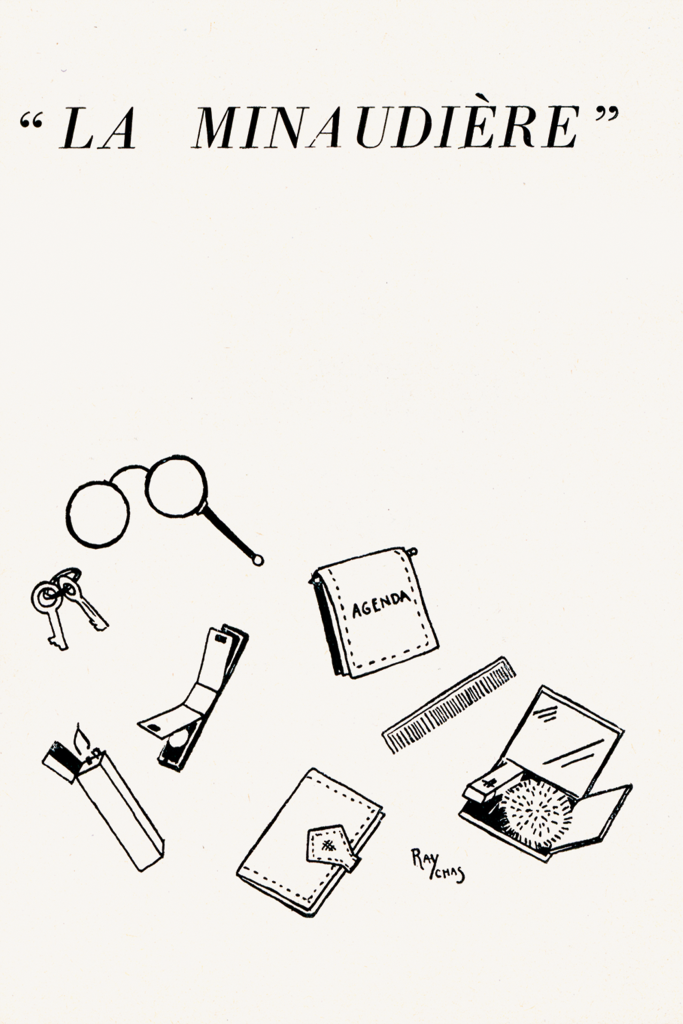

Members of the Van Cleef and Arpels families maintained the momentum for building the Maison’s reputation. They particularly focused their efforts on its creative dynamism and on the legal framework of its identity, in order to protect the results of this creativity. Throughout the 1930s, numerous trademarks and patents were registered by the Maison both in France and abroad, followed by two decisive inventions the following year: the Minaudière and the mystery set technique. While the first was a revolution in terms of form, the second was the result of several centuries of experimentation by jewelers. These two innovations were sustained by the Maison’s close collaboration with one of the designer-producers that had been working for it since the 1920s: the Langlois workshop.

Now having a manufacturing workshop and therefore no longer limited solely to trade, Van Cleef & Arpels filed a hallmark on August 29, 193318For further information on this workshop, see: Rémi Verlet, Dictionnaire des joailliers, bijoutiers et orfèvres en France de 1850 à nos jours (Paris: Gallimard, 2022), 2254–2256.—one that combined the initials of the two families on either side of the symbolic Vendôme Column.

The Maison also continued creating jewelry and watches in series with variations: following on from the Circle brooches, the Ludo bracelets in 1934 and the Padlock watches in 1935 completed its creative range. In order to produce these new models, the Maison had to expand its network of “designer-producers”: Langlois, who worked on the Minaudières, and Verger on the Padlock watches, were joined by Magnier Pinçon19For further information on this workshop, see: Rémi Verlet, Dictionnaire des joailliers, bijoutiers et orfèvres en France de 1850 à nos jours (Paris: Gallimard, 2022), 1481–1482. and Sterlé20For further information on this workshop, see: Rémi Verlet, Dictionnaire des joailliers, bijoutiers et orfèvres en France de 1850 à nos jours (Paris: Gallimard, 2022), 2147. for the jewelry. Above all, the collaboration with the Péry workshops21For further information on this workshop, see: Rémi Verlet, Dictionnaire des joailliers, bijoutiers et orfèvres en France de 1850 à nos jours (Paris: Gallimard, 2022), 1797., which began in 1930, was to prove both productive and lasting. This partnership began with pieces that required chains, like chain bracelets and watches, before moving on to the addition of jewelry elements with pieces such as the Ludo bracelet. In 1934, in order to protect this ever-growing visual identity, models were registered.

Une expansion internationale

It was not until 1936, however, that Van Cleef & Arpels turned its attention meaningfully to overseas expansion once again. On September 4, 1936, “Van Cleef & Arpels Ltd” was founded in London22Memorandum and Articles of Association of Van Cleef & Arpels Limited, September 4, 1936, Van Cleef & Arpels Archives, Paris.. That same year, the Maison pursued its aim of perfecting the jewelry technique that would allow the mount to all but disappear in favor of gemstones, the mystery set. Three additional patents were registered for the mystery set23Patent for the “Perfection of mounts of precious stones” N° 802.367, September 3, 1936, INPI, Paris. Patent for the “Mounting of precious stones”, N° 805.549, November 21, 1936, INPI, Paris. Patent for the “Perfection of methods of setting and mounting stones”, N° 801.863, August 20, 1936, INPI, Paris. and a trademark was registered24Registration of the trademark “Le Serti Mystérieux” (mystery set), N° 311911, December 14, 1936, Greffe du tribunal de commerce de Paris (Registry of the Paris commercial court). to protect the name. Patents were also registered in Great Britain, Germany, and the United States, reflecting the competitive international industrial context.

Furthermore, from 1937, the management of the Maison expanded to include the younger generation of the two families, namely Jules Arpels’ three sons, Claude (1911–1990), Jacques (1914–2008) and Pierre (1919–1980), and their cousin Renée Puissant25Procès-verbal de l’assemblée générale de la société Van Cleef & Arpels (Minutes of the general assembly of the Van Cleef & Arpels company), May 27, 1937, Van Cleef & Arpels Archives, Paris..

In 1937, the Exposition Universelle, organised in Paris and dedicated to the arts and technology, enabled Van Cleef & Arpels to show the numerous inventions implemented during the 1930s to a wide audience: the display was largely composed therefore of mystery set pieces on flat or curved mounts, together with a Minaudière. Far from limiting themselves to this Parisian success, Van Cleef & Arpels took advantage of a second international exhibition, the World’s Fair in New York, two years later, to pursue its establishment overseas, resuming projects that had been cut short by the Wall Street Crash in 1929.