Collier Broderie indienne

Détails de la création

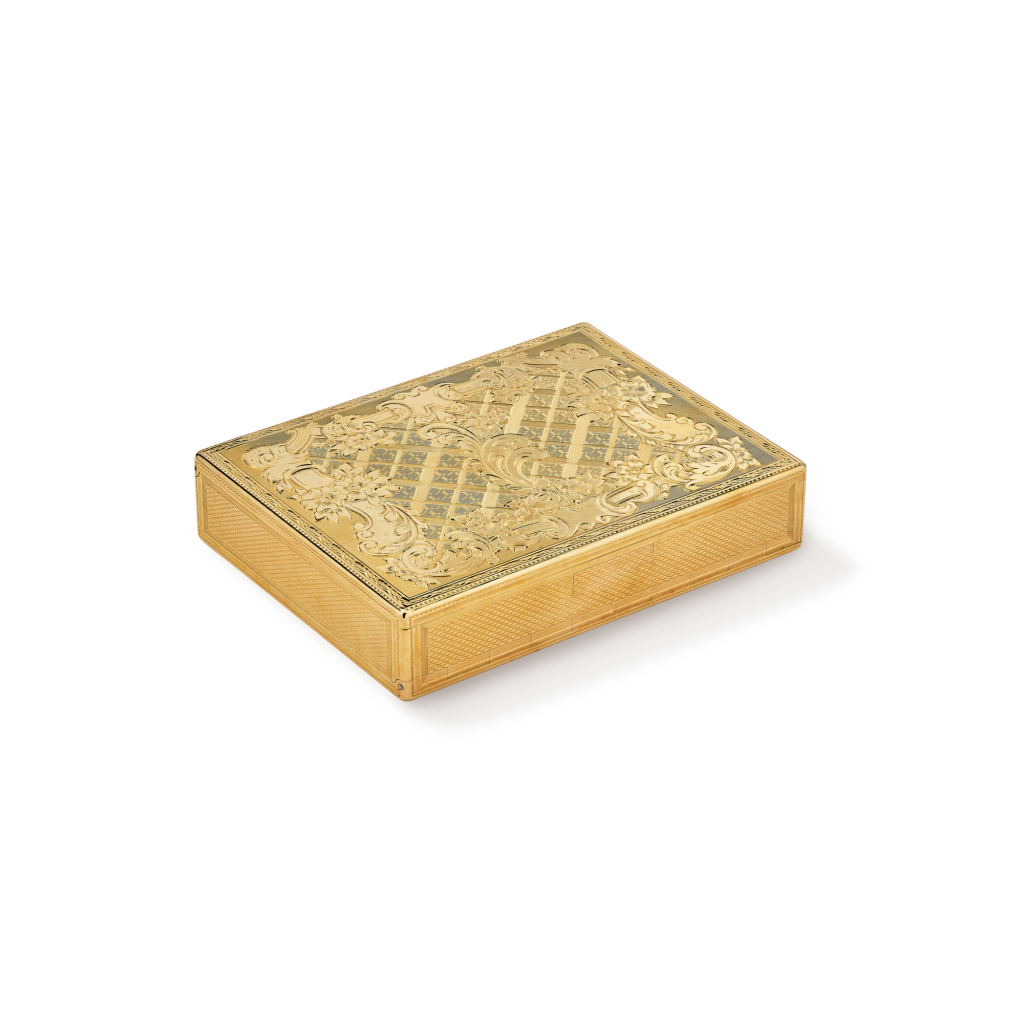

This necklace, modified in 1970 as part of a special commission, is the result of the combination of a bracelet and part of a so-called “Indian Embroidery” necklace made in 1950.

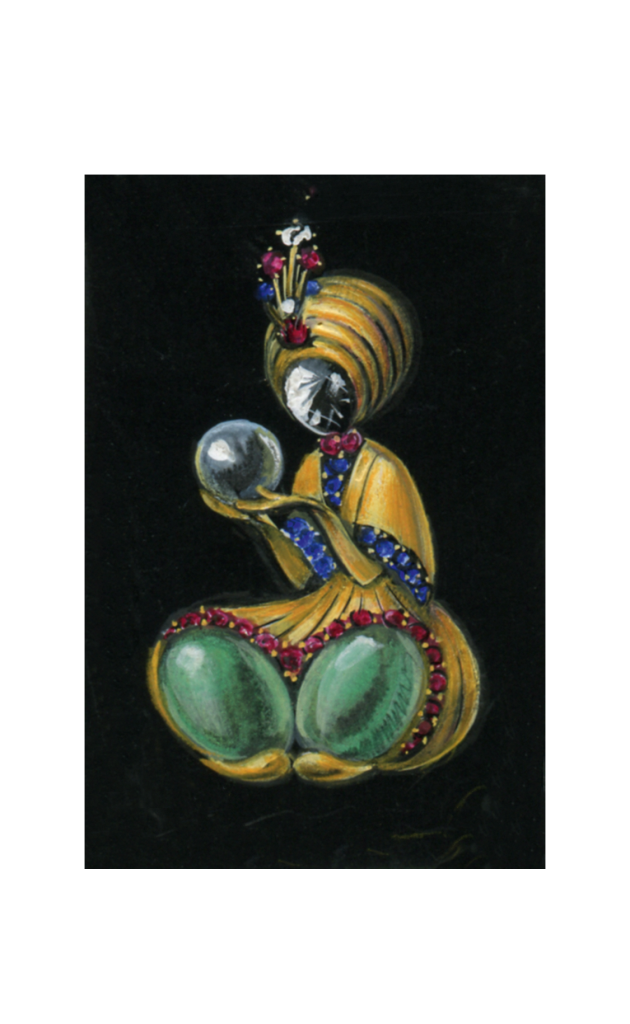

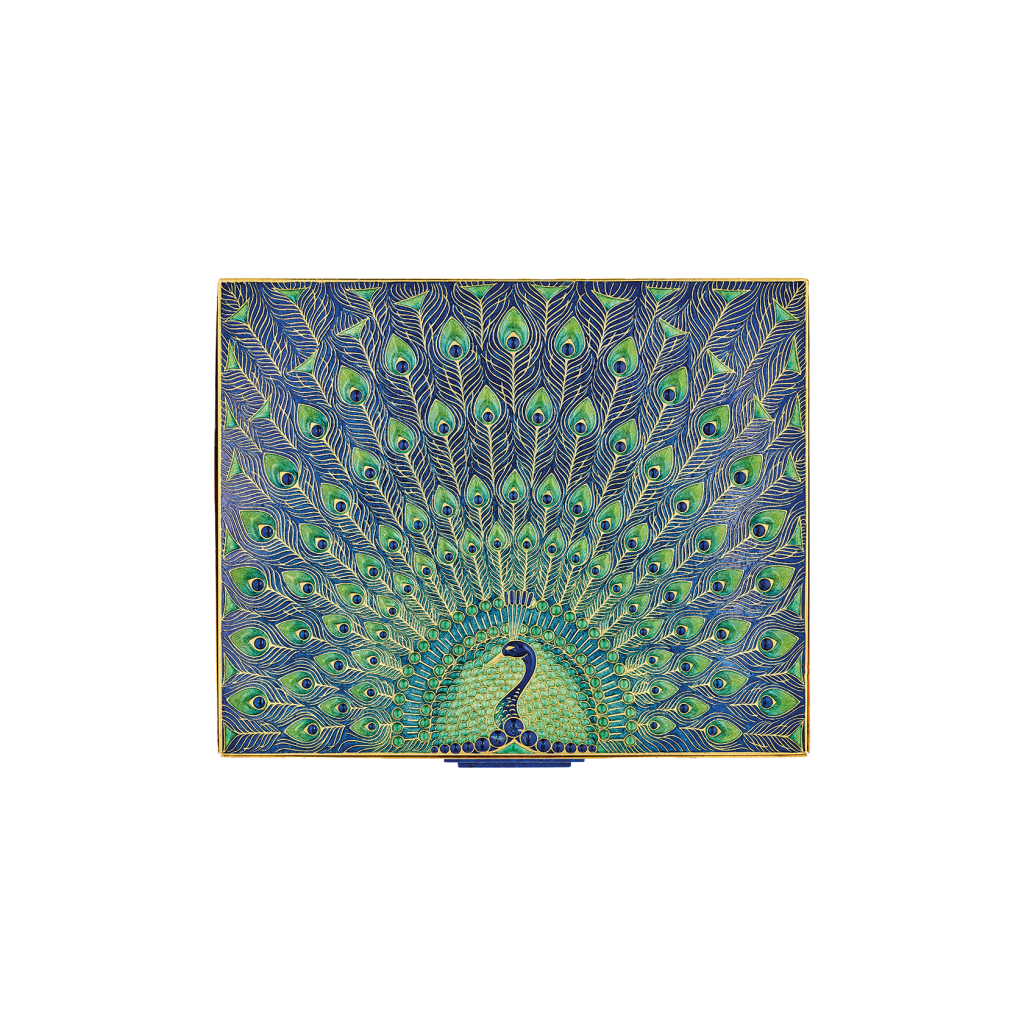

While the original form has been transformed, the design of this piece is still entirely in keeping with the 1950s style. The original bracelet and necklace were themselves very much part of the experimental work with Indian ornamentation that Van Cleef & Arpels had been undertaking since the 1920s. This choker is composed of three rows of small flowers linked together to form an lace-like openwork pattern. A bezel-set circular ruby or emerald adorns the center of each flower, surrounded by yellow gold petals outlined with twisted yellow gold thread. The flowers are linked by claw-set diamonds mounted on platinum. The whole piece is mounted on links that provide an immensely flexible structure closely espousing the curve of the neck.

The influence of India

While these small flowers are highly stylized, they nonetheless recall the opulence of the Indian decorative vocabulary. Furthermore, the association of rubies, emeralds, and diamonds with yellow gold is strongly reminiscent of the colorfulness of Indian jewelry, as aided by the coun- try’s wealth of gemstones. This early 1950s rendition, however, displays a different sensibility, translating a new stylistic approach resulting from the first voyage undertaken by Pierre and Claude Arpels to India in 1947.

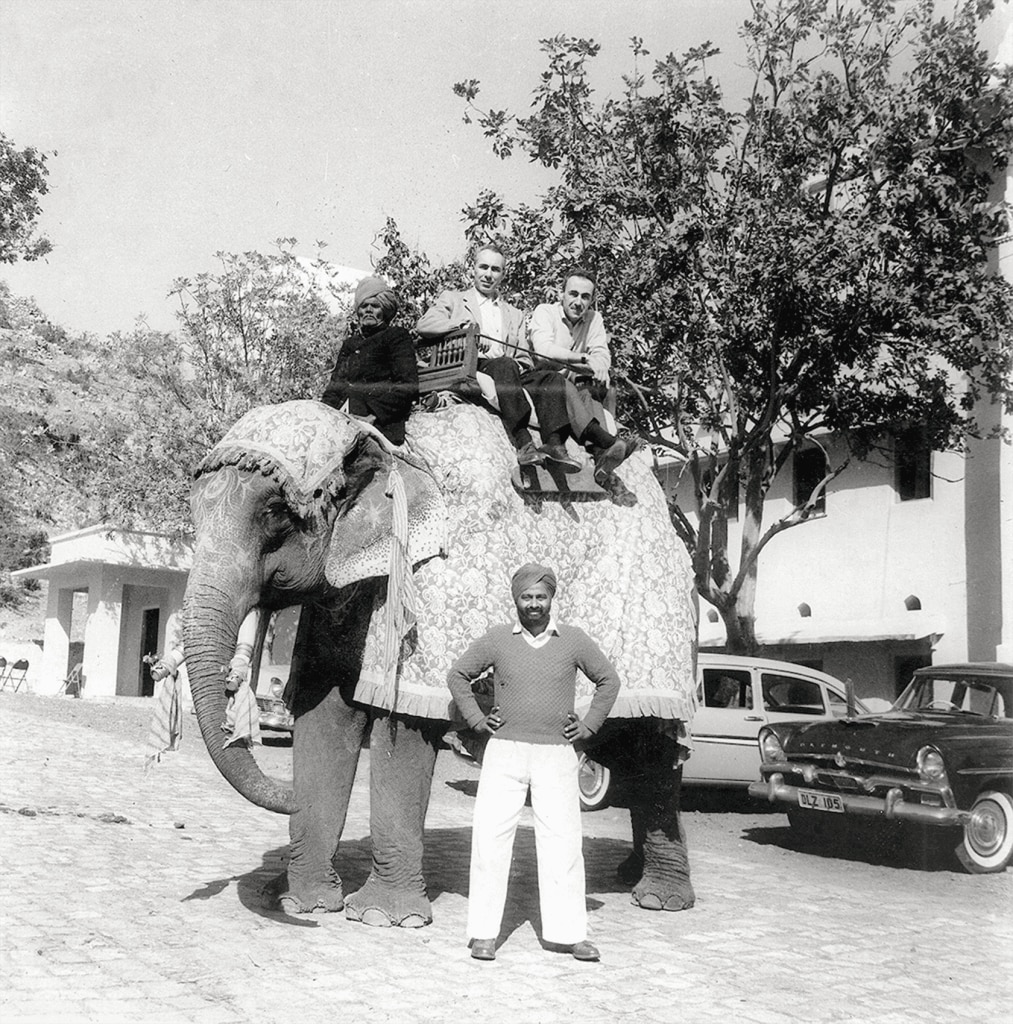

The Arpels brothers’ Indian journey

Over the years, the Arpels brothers were both to undertake no less than ten trips to India,1Christy Fox, “Claude Arpels: Living Proof of Renaissance Man Theory,” Los Angeles Times (May 12, 1969): n.p. which Claude Arpels recounted in Bejeweled Adventure,2Claude Arpels, Bejeweled Adventure, 1956. Paris, Van Cleef & Arpels Archives. a dreamlike account of their journey from Varanasi, the holy city of the Ganges, to “pink Jaipur.” During this first trip, the two brothers sought out the “fabulous precious stones that bedecked legendary maharajas.” They are marveling at the “saffron robes” and rich colors of the “markets and bazaars”. They also noted “the gold and silk brocade,” which no doubt inspired the Indian embroidery of this 1950 choker.

Creative exchanges between India and France

Claude Arpels admired Indian-style jewelry enormously, and sought to promote a “reciprocal exchange of ideas” between India and France. Balmain already used Indian fabrics, but it was Claude Arpels who incited Christian Dior to do likewise.3Christy Fox, “Claude Arpels: Living Proof of Renaissance Man Theory,” Los Angeles Times (May 12, 1969): n.p. In addition to actual gemstones, he brought “pieces of jewelry” back to France that revived the taste for the forms and colors of Indian art.4Anonymous, “Diamond King in Bombay,” Gateway Gossip (February 1957): 23. In this respect, Claude Arpels contributed to the revived enthusiasm for Central Asia from the 1950s.

Pour approfondir